History

Historic Game and Overlooked Award

Historic Game and Overlooked Award

From now until a winner of the Bill Masterton Memorial Trophy is awarded a few months from now, millions of words will be written and millions more will be spoken about this annual award to the NHL player who best personifies perseverance, sportsmanship and dedication to his game. Those words have special meaning for those who recall the sorrowful event that led to introduction of this award.

In Alberta, we’re guaranteed to hear and read that Connor McDavid of the Oilers deserves the honour because of his incredible effort in overcoming what might have been a career-ending knee injury. And that Calgary Flames captain Mike Giordano should win because he has overcome injury and does incredible things on the ice and in the community for the benefit of his team and his community.

The list of 31 candidates, all nominated by local media, was released on Tuesday and includes as many as a dozen who might have legitimate claims for the selection. Edmonton product Jay Bouwmeester, now 37, is the St. Louis Blues nominee and will get much support for his long and dignified career and the memory that quick use of a defibrillator was required to save him after he collapsed on the bench during a game last February.

Probably, the early leader is Bobby Ryan of the Ottawa Senators, who reached the NHL in 2005 as a second-overall choice by the Anaheim Ducks after surviving for years in a miserable and dangerous family situation. Another crisis was faced and defeated when he signed himself in as an alcoholic in dire need of aid, then came back to collect three goals in his first game after an absence of 104 days.

For those who see Masterton’s name only on this award, it is – and certainly should be – essential to realize he is the only NHL player to lose his life as the direct result of an incident during a game. He was a Minnesota North Stars rookie in 1968 when he attempted to split a pair of Oakland Seals (remember them?) defenders. Both defenders hit him at the same time. Masterton never regained consciousness and died in hospital 30 hours later.

No penalty was called and no serious investigation was launched. Masterton’s family understood that, in the words of one, “it could have happened to anybody.”

His too-brief career ended with four goals and eight assists. His first goal came in the opening game of the season and was the first in history for the expansion North Stars, where he signed after three brilliant years at the University of Denver.

A personal note: my job as an editor on the night shift at Canadian Press in Toronto prompted me to handle the story as it broke. From every imaginable area, there was an outbreak of sympathy. Also, there was an outbreak of calls for the mandatory use of helmets. Most players responded that they couldn’t possibly play well wearing helmets. League officials spoke almost in unison, saying the use of helmets would reduce fan interest; those who were thrilled to watch Guy Lafleur’s hair streaming behind him, for example, should not be forced to surrender such joy.

Eventually, good sense reigned. Helmets became the order of the day – but not until 1979. Any new player that season wore head protection but “grandfather” clauses were written for the comfort and convenience of those whose careers began without the headgear.

The last active player to function without a helmet was Craig MacTavish, whose consistent career – much of it with the Oilers – ended in 1997. MacT always insisted the game was safer before helmets were adopted. Bill Masterton did not get to vote on the question.

Central Alberta

Local artist records original song for Remembrance Day with video showcasing Red Deer’s military history

Editor’s note: This article was published in 2020. It was extremely popular in the Central Alberta region so we wanted to circulate it again this year, now even more poignant with the war in Ukraine. The video uses many images that are familiar to Central Albertans and pays tribute to Central Alberta soldiers who have deployed internationally over the years.

This spring, a singer and songwriter friend of mine from Red Deer, Shelly Dion, came to me with a song idea that had, in her words, been “knocking around in my head for the past 30 years”. She said that she really wanted to pay her respects to the people who sacrificed their lives and livelihoods to go to war.

The song is called “Lay Me Down”, and it’s a very fitting song for this time of year. We decided to get together and record a simple version of the song. Then I sent her off to see musical wizard, Red Deer’s Heath West of Medodius Design. Heath came up with some excellent improvements and we recorded it in his studio this fall.

As Honorary Colonel of 41 Signal Regiment in Alberta, I’m always looking for opportunities to promote the military, our Regiment’s members, and of course at this time of year, to acknowledge the sacrifice made by the men and women who serve in the Canadian Armed Forces. “Lay Me Down” hit all the right notes.

With some help from Counsellor Michael Dawe, long-time archivist for the City of Red Deer, I gained access to some wonderful historic photos that helped me to tell some of the stories of Red Deer’s military history. At the same time, I wanted to help the members of our Regiment honour the many local members who have volunteered to put their lives and careers on hold to deploy internationally to places like Afghanistan, Golan Heights, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, and more recently Ukraine and Latvia. This project allowed me to both profiles some local history and recognize our more modern history. Thanks to WO Drew Adkins of 41 Signal Regiment for his help in coordinating photos from our wall of fame inside Cormack Armoury.

The above video is the result. Take some time to learn about our local military history. Do you know who Cormack Armoury is named after? You’ll also learn about local members of 41 Signal Regiment (2 Sqn), many of whom actively serve in the Armed Forces today. You may even know some of them as neighbours, friends, and co-workers. Please take a moment to acknowledge their service, and on November 11th, attend a service, and at the very least, take a moment at 11 AM to be silent and consider how lucky we are to be at peace in our country.

“Lay Me Down” is written and performed by Shelly Dion and produced and engineered by Heath West. Musicians: Bagpipes Glenn MacLeod, acoustic guitar Heath West, electric guitars Lloyd Lewis, drums Phil Liska, Bass Doug Gagnon.

Click to read more on Todayville.

City of Red Deer

The rich and sobering history of Red Deer’s “Unknown Soldier”

The origins of Red Deer’s beautiful Cenotaph date back to the end of WWI. The statue of the Unknown Soldier is a provincial historic site. In this article, historian and author Michael Dawe helps us understand the rich history of this monument and reminds us all of the sacrifices of our forebearers. Enjoy the photo gallery showing the changes to the Cenotaph and its surroundings over the years.

The Cenotaph by Michael Dawe (originally published Nov. 9, 2019)

There are many memorials around the City of Red Deer to honour those who served and those who lost their lives during a time of war. The main community memorial is the Cenotaph, the statue of the Unknown Soldier that stands in the centre of Ross Street in the heart of downtown Red Deer.

- Cenotaph 1930’s Red Deer Archives P2949

- Cenotaph and boulevard looking east 1922, Red Deer Archives

- Cenotaph 1927 Red Deer Archives N268

- Cenotaph 1943 Red Deer Archives S2282

- Cenotaph c. 1947 Red Deer Archives P2832

- Cenotaph h 1930’s P2949

- Honour Guard at the unveiling of the Cenotaph, September 15, 1922, Red Deer Archives P2700

- Unveiling of Cenotaph, September 15, 1922, Red Deer Archives P2700

- Unknown Soldier Statue before installation, 1922 Red Deer Archives P2759

- Cenotaph 1960s Waskasoo Camera Club

- Cenotaph, 1983 Red Deer Archives S480

- Cenotaph 2001, City of Red Deer

- Cenotaph, 1954 N5939

- Cenotaph 1954 N3596

- Cenotaph Ceremonies 2014 Frank Wong

- Cenotaph c. 1950 Waskasoo Camera Club

- Cenotaph 1948 Waskasoo Camera Club

- Cenotaph c. 1950 Red Deer Archives P3280

- Unknown Soldier 2016 c. Lloyd Lewis

- Veterans Park and Unknown Soldier 2016 c. Lloyd Lewis

The origins of the Cenotaph go back to the end of the First World War. That conflict had been a searing experience for Red Deer. 850 young men and women from the City and surrounding districts had enlisted. Of these, 118 lost their lives. Of those who returned, many had suffered terrible wounds and faced a lifetime of ill health and suffering. Hence, it was extremely important to the community that a fitting and very special memorial be created.

On December 18, 1918, five weeks after the end of the War, the Central Alberta local of the Great War Veterans Association (forerunner of the Royal Canadian Legion) organized a large public meeting to discuss the creation of such a memorial. Three proposals were initially made. The first was to construct a pyramidal monument of river cobblestones in the centre of the City. The second was to construct a community hall and recreation facility next to City Hall. The third was to purchase the old Alexandra (Park) Hotel and turn it into a community centre.

After considerable discussion, a fourth proposal was adopted. It was decided to build a monument rather than a community centre. However, at the suggestion of Lochlan MacLean, it was also decided that this monument be in the form of a statue of a soldier, mounted on a pedestal, rather than a cobblestone pyramid or obelisk.

Major Frank Norbury, an architectural sculptor at the University of Alberta and a veteran of the War, was commissioned to carve the statue. He came up with the concept of carving the Unknown Soldier as he was coming off active duty on the front line. He was to face west, toward home and peace. He was also to be positioned towards the C.P.R. station from which most of the soldiers had left Red Deer for the War.

This latter point was one of the greatest controversies about the Cenotaph. City Council and a few others wanted it in the centre of the City Square (now City Hall Park). However, the majority wanted it facing directly towards the station and in the middle of Ross Street, Red Deer’s busiest thoroughfare, so that it would be a constant reminder of the sacrifices of the War.

Meanwhile, fundraising for the project commenced, but proved quite a challenge. Post-war Red Deer faced one of the worst economic depressions in its history. However, despite the general shortage of money, by the following summer more than half of the $6200 needed had been raised. Unfortunately, Red Deer City Council decided that given its financial situation, it could not contribute any money to the project. This decision reinforced the opinion of the Memorial Committee that Council’s wish to have the Cenotaph in the middle of the City Square should be ignored.

There were still a lot of hard feelings about that lack of official City participation. Eventually, City Council agreed to build a boulevard in the middle of Ross Street, west of 49 Avenue, as a site for the Cenotaph. A decision was also made to place street lights at either end of that boulevard to provide nighttime illumination of the spot.

There was another debate regarding the proper means of recording the names of those killed in the War. Some wanted tablets placed on the pedestal. However, the Memorial Committee was worried about having a complete and accurate list. Finally, it was agreed to have two scrolls prepared, one with the names of those who had served and one with the names of those who had lost their lives. Both scrolls were put into a copper tube and placed in a cavity in the pedestal.

On September 15, 1922, the Cenotaph was officially unveiled. To the delight of the community, Governor General Lord Byng of Vimy agreed to come and do the honours. Lord Byng was a hero of one of Canada’s most significant military victories, the Battle of Vimy Ridge. Vimy was also a victory that had also come with very heavy loss of life, both locally and nationally.

At the time of the official unveiling, it was reported that the Cenotaph was the first sculpture war memorial in Alberta. Once the official dedication was completed, the monument was placed into trust with the City on behalf of those who had contributed to its creation.

The Cenotaph was rededicated in 1949 to include remembrance of those who served and lost their lives in the Second World War. A plaque signifying that designation was added to the pedestal. After the completion of the new City Hall Park and the Memorial Centre in the early 1950’s. there was a push to relocate the Cenotaph from its location on Ross Street to either the centre of City Hall Park or a new site in front of the Memorial Centre. However, a plebiscite was held in 1953 in which the citizens of Red Deer voted to keep the Cenotaph were it was.

Another plaque was added in 1988 in memory of those who served and died in the Korean Conflict. At the same time, through the efforts of some dedicated members of the public, special lighting was added to ensure that the Cenotaph was highly visible at night.

There were new proposals in the 1990’s to relocate the Cenotaph to City Hall Park. However, Charlie Mac Lean, son of Lochlan MacLean and one of the last surviving people to have actually built the Cenotaph, offered the opinion that he did not think that the monument could be safely relocated.

In 2006, the Cenotaph was extensively cleaned and repaired. City Council then successfully applied to have the Cenotaph designated as a Provincial Historic Site. In 2010-2011, a beautiful Veterans’ Park was created around the Cenotaph, to enhance it and to make it more accessible to the public. Moreover, eight interpretive panels were created to let people know the full significance of Red Deer’s official war memorial. They give the stories of those who served in the Boer War, First World War, Second World War, Korean Conflict, the Afghanistan War and all the peace-keeping and peace-making missions in which Canadians have been involved.

Lest We Forget.

Michael Dawe

Here are some other local history stories you might enjoy

Armistice Day 11/11/1918 from a Red Deer perspective in pictures and story

-

COVID-1919 hours ago

COVID-1919 hours agoCDC Quietly Admits to Covid Policy Failures

-

Brownstone Institute10 hours ago

Brownstone Institute10 hours agoDeborah Birx Gets Her Close-Up

-

COVID-1922 hours ago

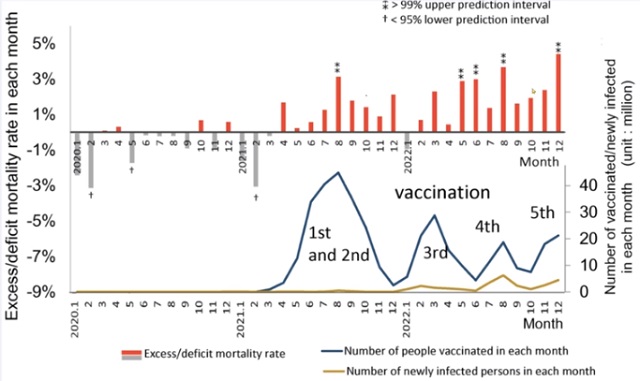

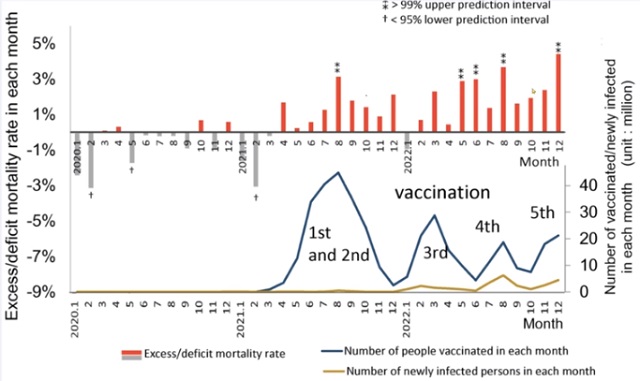

COVID-1922 hours agoJapanese study shows disturbing increase in cancer related deaths during the Covid pandemic

-

espionage2 hours ago

espionage2 hours agoConservative MP testifies that foreign agents could effectively elect Canada’s prime minister, premiers

-

Great Reset17 hours ago

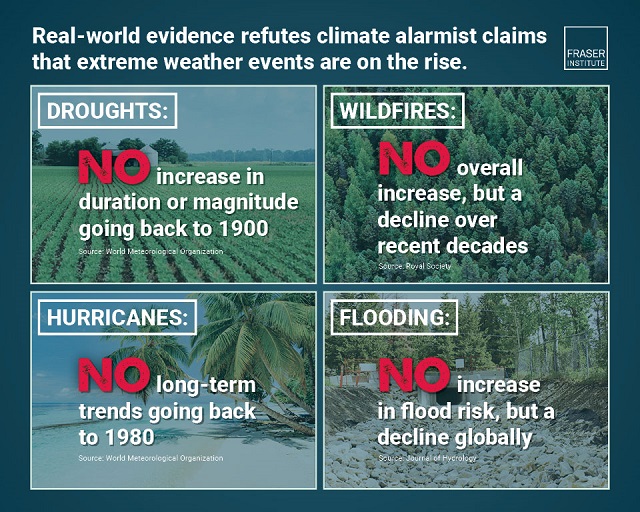

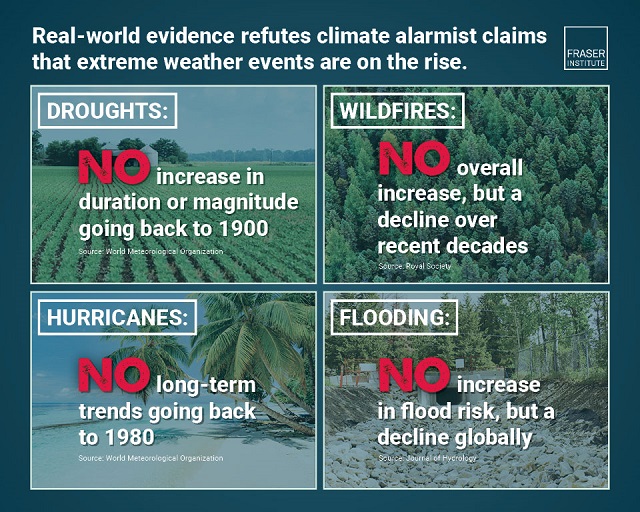

Great Reset17 hours agoClimate expert warns against extreme ‘weather porn’ from alarmists pushing ‘draconian’ policies

-

Health1 hour ago

Health1 hour agoQuadriplegic man dies via euthanasia after developing bed sores waiting at Quebec hospital

-

Economy2 days ago

Economy2 days agoExtreme Weather and Climate Change

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoWhy Are Canadian Mayors So Far Left And Out Of Touch?