Agriculture

Why the News Block on the Plight of Dutch Farmers?

From the Brownstone Institute

BY

God made the world, but the Dutch made Holland. This truism has guided Dutch identity and its republican virtue. When the ingenious Dutch reclaimed land from the sea it was for farms and these farms and farmers have fed the Dutch people, Europe and the world for centuries.

The picture displayed here is Paulus Potter’s famous work The Bull.

Created in 1647, Potter was 22 when he painted it and not quite 30 when he died. Renowned for its massive size, detailed realism including dung and flies and as a novel monumental picture of an animal, The Bull is understood as a symbol of the Dutch nation and its prosperity.

The Dutch Golden Age resulted in part from the creation of the Dutch Republic carved out by overcoming Spanish rule in the Netherlands. The little Dutch Republic became a global naval power and cultural force. The Dutch were classical liberals and believed in individual liberties like freedom of religion, speech and association.

The Dutch Republic was noted for economic vibrancy and innovation including the emergence of commodity and stock markets. The newly minted bourgeoisie spurred the first modern marketplace for artists to sell their work and freed them from the necessity of commissions from the Church and aristocracy. This is reflected in the subject matter of much Dutch Golden Age art with its depiction of everyday life. Potter’s painting is from this era.

But his work reveals another truth. The Dutch Golden age was impossible without its farms. Food is the foundation of any successful civilization, which is why the news that the Dutch government plans to shut as many as 3,000 farms for the sake of a ‘’nitrogen crisis’’ is so puzzling.

As Natasja Oerlemans of the World Wildlife Fund-Netherlands recently stated, ‘’We should use this crisis to transform agriculture.” She went on to state that the process will require several decades and billions of euros to reduce the number of animals.

So, what in fact is the issue with nitrogen and Dutch farming?

The nitrogen crisis is a bureaucratic and muddled affair which is now and will increasingly impact all of Dutch society. In 2017 a small NGO, Mobilisation for the Environment, led by long-time environmentalist Johan Vollenbroek, went to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) to challenge the then current Dutch practices that protected natural areas from nitrogen pollution.

In 2018, the ECJ decided in a court ruling that the Dutch legislation, which allowed business to compensate for increases in nitrogen emissions with technical measures and restoration, was too lenient. The Dutch high court agreed with the ruling. In so doing almost 20,000 building projects have been put on hold, stalling the expansion of farms and dairies, new homes, roads, and airport runways. These projects are valued at €14 billion of economic activity.

Farming is intensive in the Netherlands because it is a small country with high population density. According to Science magazine ‘’Dutch farms contain four times more animal biomass per hectare than the EU average.’’ But they also point out that ‘’Practices such as injecting liquid manure in the soil and installing air scrubbers on pig and poultry facilities have reduced ammonia emissions 60% since the 1980s.’’

These mitigating systems are seen as insufficient in light of the court rulings. Ammonia is part of the nitrogen cycle and is a byproduct of waste from farm animals.

The great concern of environmental bureaucrats is the so-called ‘’manure fumes’’ from livestock waste. Like methane from farting cows, manure fumes are the big thing and katzenjammer of the movement on meat and dairy.

Dutch farmer Klass Meekma, who produces milk from the goats he raises said recently, ‘’The nitrogen rules are eagerly being used by the anti-livestock movement to get rid of as many livestock farms as they can, with absolutely no respect for what Dutch livestock farms have achieved in terms of food quality, use of leftovers of the food industry, animal-care, efficiency, exports, know-how, economics and more.’’ Meekma’s goats produced more than 265,000 gallons of milk in 2019.

In many ways, Dutch farmers are the victims of their own success. Because Holland is small, farmers have needed to be innovative in the use of space which accounts for the higher levels of ‘’animal biomass’’ compared with other European countries. Success in agricultural practices and food production has produced profits and a strong economic sector for the Dutch economy. Remarkably, the Netherlands is the second largest food exporter in the world.

The biggest push against Dutch agriculture comes from the climate change community and minister for nature and nitrogen Christianne van der Wal. She said in a letter to politicians in 2021, “There is no future (for agriculture) if production leads to depletion of the soil, groundwater and surface water, or degradation of ecosystems.” She has announced new restrictions to cut nitrogen emissions in half by 2030, to meet international climate action goals.

Nobody wants runoff from farms harming streams and wildlife. But the focus on manure fumes; that is, nitrogen and ammonia seeping into the atmosphere and impacting the climate seems far more tenuous. Primeval Europe was like Africa’s Serengeti, teeming with huge herds of ungulates like aurochs. Did their farting and waste ruin the climate?

The climate is changing. The climate has always changed. Bronze Age Europe, a particularly fecund cultural period, was markedly warmer than today.

It is curious that the farming sector is the focus of rollbacks while other polluters are being treated differently. Farmer Meekma states,

“Since then (the court rulings) our country has a so-called nitrogen crisis. It’s ludicrous that the national airport Schiphol Amsterdam and lots of industrial companies have no nature permits, and farmers are now being sacrificed to facilitate these other activities.”

“It’s a real shame how farmers are being treated in the Netherlands. They are being pushed out to make room for industry, aviation, transportation, solar fields and housing of the growing numbers of immigrants.’’

Most of the “saved” nitrogen emissions from government plans will be used to offset the increased emissions from building 75,000 houses. Only 30 percent will lead to real emission reductions.

Dutch Prime Minister and WEF luminary Mark Rutte acknowledged that the move on farming would have “enormous consequences. I understand that, and it is simply terrible.”

There are many historical examples of political pressures on farming as harbingers of disaster, from Ukraine in the Soviet Union to Zimbabwe. Both were breadbaskets and exporters reduced to famine. Controlling food production is something that political ruffians always want to achieve. The nitrogen crisis is a struggle of urban ideologues versus traditional lifeways and rural self-sufficiency. Due to the war in Ukraine and supply-chain disruption from the covid pandemic, many people around the world are facing starvation. This is not the time for Europe to harm its best agricultural producer.

Dutch farmers are hip to when a nudge becomes a shove. The anti-meat ideologues want humans to subsist on grass cuttings and Bill Gates’ lab-made gunk. Dutch farmers feed the world. Their plight is ours as well.

The nitrogen crisis has the waft of so much bullshit.

Agriculture

Bill C-282, now in the Senate, risks holding back other economic sectors and further burdening consumers

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Bill C-282 currently sits in the Canadian Senate and stands on the precipice of becoming law in a matter of weeks. Essentially, this bill seeks to bestow immunity upon supply management from any potential future trade negotiations without offering increased market access to potential trade partners.

In simpler terms, it risks holding all other economic sectors hostage solely to safeguard the interests of a small, privileged group of farmers. This is far from an optimal scenario, and the implications of this bill spell bad news for Canadians.

Supply management, which governs poultry, egg, and dairy production in Canada, has traditionally enabled us to fulfill our domestic needs. Under this system, farmers are allocated government-sanctioned quotas to produce food for the nation. At the same time, high tariffs are imposed on imports of items such as chicken, butter, yogurt, cheese, milk, and eggs. This model has been in place for over five decades, ostensibly to shield family farms from economic volatility.

However, despite the implementation of supply management, Canada has witnessed a comparable decline in the number of farms as the United States, where a national supply management scheme does not exist. Supply management has failed to preserve much of anything beyond enriching select agricultural sectors.

For instance, dairy farmers now possess quotas valued at over $25 billion while concurrently burdening dairy processors with the highest-priced industrial milk in the Western world. Recent data indicates a significant surge in prices at the grocery store, with yogurt prices alone soaring by over 30 percent since December 2023. This escalation is increasingly straining the budgets of many consumers.

It’s evident to those knowledgeable about the situation that the emergence of Bill C-282 should come as no surprise. Proponents of supply management exert considerable influence over politicians across party lines, compelling them to support this bill to safeguard the interests of less than one percent of our economy, much to the ignorance of most Canadians. In the last federal budget, the dairy industry alone received over $300 million in research funds, funds that arguably exceed their actual needs.

While Canada’s agricultural sector accounts for approximately seven percent of our GDP, supply-managed industries represent only a small fraction of that figure. Supply-managed farms represent about five percent of all farms in Canada. Forging trade agreements with key partners such as India, China, and the United Kingdom is imperative not only for sectors like automotive, pharmaceuticals, and biotechnology but for the vast majority of farms in livestock and grains to thrive and contribute to global welfare and prosperity. It is essential to recognize that Canada has much more to offer than merely self-sufficiency in food production.

Over time, the marketing boards overseeing quotas for farmers have amassed significant power and have proven themselves politically aggressive. They vehemently oppose any challenges to the existing system, targeting politicians, academics, and groups advocating for reform or abolition. Despite occasional resistance from MPs and Senators, no major political party has dared to question the disproportionate protection afforded to one sector over others. Strengthening our supply-managed sectors necessitates embracing competition, which can only serve to enhance their resilience and competitiveness.

A recent example of the consequences of protectionism is the United Kingdom’s decision to walk away from trade negotiations with Canada due to disagreements over access to our dairy market. Not only do many Canadians appreciate the quality of British cheese, but increased competition in the dairy section would also help drive prices down, a welcome relief given current economic challenges.

In the past decade, Canada has ratified trade agreements such as CUSMA, CETA, and CPTPP, all of which entailed breaches in our supply management regime. Despite initial concerns from farmers, particularly regarding the impact on poultry, eggs, and dairy, these sectors have fared well. A dairy farm in Ontario recently sold for a staggering $21.5 million in Oxford County. Claims of losses resulting from increased market access are often unfounded, as farmer boards simply adjust quotas when producers exit the industry.

In essence, Bill C-282 represents a misguided initiative driven by farmer boards capitalizing on the ignorance of urban residents and politicians regarding rural realities. Embracing further protectionism will not only harm consumers yearning for more competition at the grocery store but also impede the growth opportunities of various agricultural sectors striving to compete globally and stifle the expansion prospects of non-agricultural sectors seeking increased market access.

Dr. Sylvain Charlebois is senior director of the agri-food analytics lab and a professor in food distribution and policy at Dalhousie University.

Agriculture

How oil and gas support food security in Canada and around the world

General view of the ‘TD Canadian 4-H Dairy Classic Showmanship’ within the 101st edition of Royal Agricultural Winter Fair at Exhibition Place in Toronto, Ontario, on November 6, 2023. The Royal is the largest combined indoor agriculture fair and international equestrian competition in the world. Getty Images photo

From the Canadian Energy Centre

‘Agriculture requires fuel, and it requires lubricants. It requires heat and electricity. Modern agriculture can’t be done without energy’

Agriculture and oil and gas are two of Canada’s biggest businesses – and they are closely linked, industry leaders say.

From nitrogen-based fertilizer to heating and equipment fuels, oil and gas are the backbone of Canada’s farms, providing food security for Canadians and exports to nearly 200 countries around the world.

“Canada is a country that is rich in natural resources, and we are among the best, I would even characterize as the best, in terms of the production of sustainable energy and food, not only for Canadians but for the rest of the world,” said Don Smith, chief operating officer of the United Farmers of Alberta Co-operative.

“The two are very closely linked together… Agriculture requires fuel, and it requires lubricants. It requires heat and electricity. Modern agriculture can’t be done without energy, and it is a significant portion of operating expenses on a farm.”

The need for stable food sources is critical to a global economy whose population is set to reach 9.7 billion people by 2050.

The main pillars of food security are availability and affordability, said Keith Currie, president of the Canadian Federation of Agriculture (CFA).

“In Canada, availability is not so much an issue. We are a very productive country when it comes to agriculture products and food products. But food affordability has become an issue for a number of people,” said Currie, who is also on the advisory council for the advocacy group Energy for a Secure Future.

The average price of food bought in stores increased by nearly 25 per cent over the last five years, according to Statistics Canada.

Restricting access to oil and gas, or policies like carbon taxes that increase the cost for farmers to use these fuels, risk increasing food costs even more for Canadians and making Canadian food exports less attractive to global customers, CFA says.

“Canada is an exporting nation when it comes to food. In order for us to be competitive we not only have to have the right trade deals in place, but we have to be competitive price wise too,” Currie said.

Under an incredible Saskatchewan sky, a farmer walks toward his air seeder to begin the process of planting this year’s crop. Getty Images photo

Canada is the fifth-largest exporter of agri-food and seafood in the world, exporting approximately $93 billion of products in 2022, according to Agriculture Canada.

Meanwhile, Canadians spent nearly $190 billion on food, beverage, tobacco and cannabis products in 2022, representing the third-largest household expenditure category after transportation and shelter.

Currie said there are opportunities for renewable energy to help supplement oil and gas in agriculture, particularly in biofuels.

“But we’re not at a point from a production standpoint or an overall infrastructure standpoint where it’s a go-to right away,” he said.

“We need the infrastructure and we need probably a lot of incentives before we can even think about moving away from the oil and gas sector as a supplier of energy right now.”

Worldwide demand for oil and gas in the agriculture sector continues to grow, according to CEC Research.

Driven by Africa and Latin America, global oil use in agriculture increased to 118 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) in 2022, up from 110 million tonnes in 1990.

Demand for natural gas also increased — from 7.5 Mtoe in 1990 to 11 Mtoe in 2022.

Sylvain Charlebois, senior director, in the Agri-Food Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University, said food security depends on three pillars – access, safety, and affordability.

“Countries are food secure on different levels. Canada’s situation I think is envious to be honest. I think we’re doing very well compared to other countries, especially when it comes to safety and access,” said Charlebois.

“If you have a food insecure population, civil unrest is more likely, tensions, and political instability in different regions become more of a possibility.”

As a country, access to affordable energy is key as well, he said.

“The food industry highly depends on energy sources and of course food is energy. More and more we’re seeing a convergence of the two worlds – food and energy… It forces the food sector to play a much larger role in the energy agenda of a country like Canada.”

-

Opinion19 hours ago

Opinion19 hours agoTransgender ideology has enabled people to ‘identify’ as amputees

-

International17 hours ago

International17 hours agoGerman parliament passes law allowing minors to change their legal gender once a year

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoTelegram founder tells Tucker Carlson that US intel agents tried to spy on user messages

-

Business24 hours ago

Business24 hours agoCanada’s economy has stagnated despite Ottawa’s spin

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoNew capital gains hike won’t work as claimed but will harm the economy

-

Agriculture2 days ago

Agriculture2 days agoBill C-282, now in the Senate, risks holding back other economic sectors and further burdening consumers

-

Alberta2 days ago

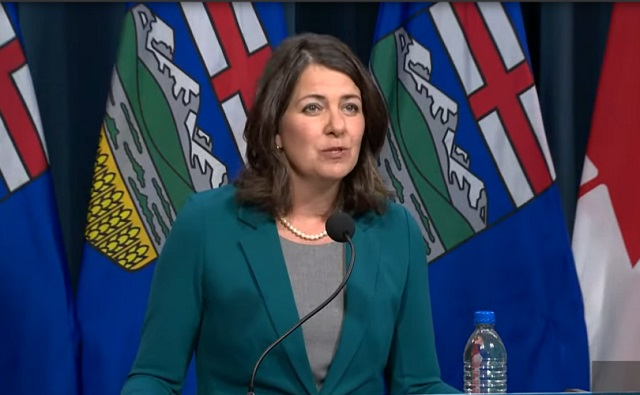

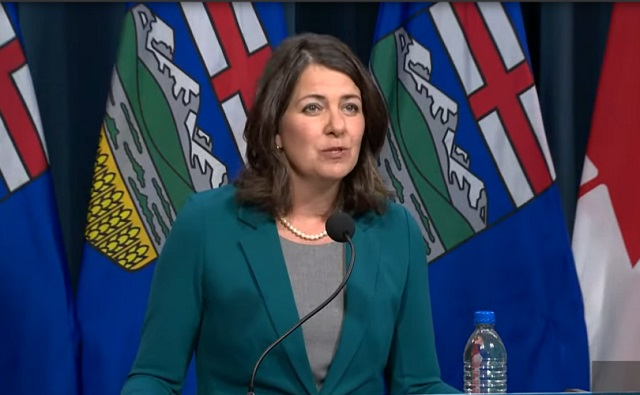

Alberta2 days agoDanielle Smith warns arsonists who start wildfires in Alberta that they will be held accountable

-

Economy1 day ago

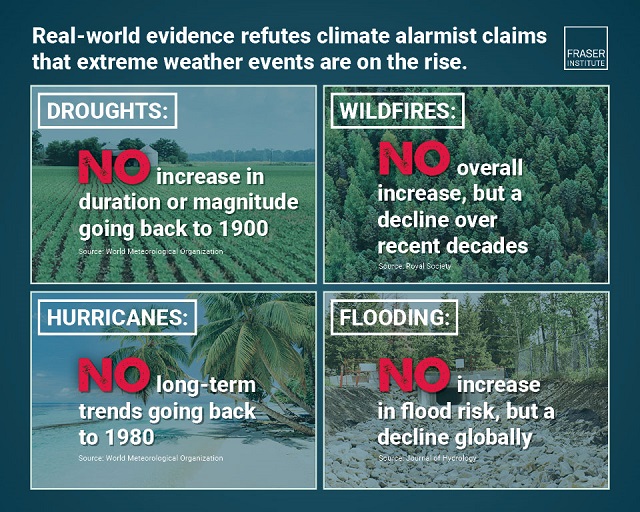

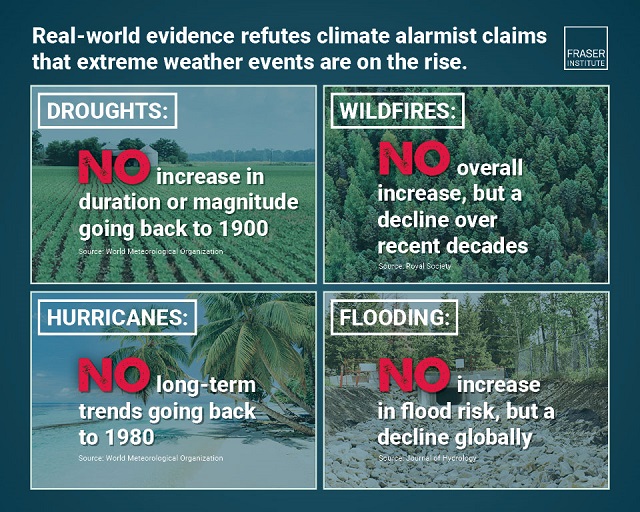

Economy1 day agoExtreme Weather and Climate Change