Opinion

What We Don’t Know About The Presidents We Elect

The Navy proudly draws its newest, most devastating fighter, the McDonnell F4H Phantom II past the applauding President of the United States John F. Kennedy as he reviews the Inaugural Parade, in Washington, DC, on January 20, 1961. / Photo by Bettmann via Getty Images.

Notes on the occasion of an inauguration

Like most Americans, I applaud the recent ceasefire agreement between Israel and Hamas that was approved today by the Israeli security cabinet, and I was glad to learn that the incoming Trump administration was directly involved in support of the Biden team in the most positive way: by telling Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that a deal had to be made.

I did not like much of the Biden administration’s foreign policy, and I worried a lot, as a journalist and a citizen, about what Donald Trump’s new team would do. But I learned long ago that you cannot tell a presidency by its cover.

In late 1967 I was a freelance journalist in Washington and totally hostile to the ongoing American war in South Vietnam. I was persuaded to join the then nascent staff of the only Democratic member of the Senate, Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, who was willing to take on President Lyndon B. Johnson, a fellow Democrat, then running for second term, who had escalated the war he inherited with mass bombing campaigns. I would be the press secretary and, while traveling with the candidate, draft daily policy statements and work on speeches.

McCarthy, a member of the Foreign Relations Committee, was far from a shining star. But, as a devout Catholic, he saw the Vietnam War in moral terms and was troubled by the Pentagon’s decision to lower the minimal acceptable scores on the Army’s standard intelligence tests in an effort to enlist more young men from the ghettos and barrios of America, where educational opportunities were fewer, as they still are today. McCarthy publicly called such action “changing the color of the corpses.” He quickly became my man.

A few weeks into the job, I was traveling with McCarthy on a fundraising tour in California and found myself outside a Hollywood mansion where McCarthy was making a money pitch to the rich and famous. Such events were always boring, and I found myself hanging around outside the mansion with a few of the local and national reporters tagging along. One of those outside was Peter Lisagor, then the brilliant Washington bureau chief for the Chicago Daily News. He had joined our antiwar campaign out of curiosity, I suspected, since the chances of forcing Johnson to change his aggressive Vietnam policy seemed to be nil amid relentless US bombings. As I later learned, Lisagor had been one of the few journalists invited to fly in 1966 on Air Force One with the president on one of his early trips to Vietnam. The flight was kept secret until Johnson arrived in Saigon.

Lisagor told me a story—most likely he meant to cheer me up, since we were polling at 5 percent at the time—about time he had spent in 1961 at Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. I do not recall whether he was on a reporting project there—he had been a Nieman fellow at Harvard in 1948—but there he was on inauguration day of 1961, while in Washington the glamorous John F. Kennedy was being sworn in as president by Chief Justice Earl Warren.

As Lisagor told it, he was watching the swearing in with a bunch of MIT students and faculty members at a cafeteria that had a TV, and just as Warren pronounced JFK president a young faculty member named Noam Chomsky stunned the small crowd by saying, of Kennedy and his Harvard ties: “And now the terror begins.”

Chomsky’s point, as would become clear in his later writings, was that Kennedy’s notion of American exceptionalism was not going to work in Vietnam. As it did not. And Lisagor’s point to me, as I came to understand it over the years, was that one cannot always tell which president will become a peacemaker and which will become a destroyer. Lisagor died, far too young at age 61, in 1976.

Joe Biden talked peace—and withdrew US forces from Afghanistan—but helped put Europe, and America, into a war against Russia in Ukraine and supported Benjamin Netanyahu’s war against Hamas and, ultimately, against the Palestinian people in Gaza.

Donald Trump is always talking tough but one of his first major foreign moves after winning the presidency was to order his senior aides to work with Biden’s foreign policy people to perhaps end a war in Gaza and save untold thousands of lives. And I hear serious talks are underway to bring an end to the Ukraine War.

One never knows.

Subscribe to Seymour Hersh.

For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

C2C Journal

Canada Desperately Needs a Baby Bump

The 21 st century is going to be overshadowed by a crisis that human beings have never faced before. I don’t mean war, pestilence, famine or climate change. Those are perennial troubles. Yes, even climate change, despite the hype, is nothing new as anyone who’s heard of the Roman Warm Period, the Mediaeval Warm Period or the Little Ice Age will know. Climate change and the others are certainly problems, but they aren’t new.

But the crisis that’s coming is new.

The global decline in fertility rates has grown so severe that some demographers now talk about “peak humanity” – a looming maximum from which the world’s population will begin to rapidly decline. Though the doomsayers who preach the dangers of overpopulation may think that’s a good development, it is in fact a grave concern.

In the Canadian context, it is doubly worrisome. Our birth rates have been falling steadily since 1959. It was shortly after that in the 1960s when we began to build a massive welfare state, and we did so despite a shrinking domestically-born population and the prospect of an ever-smaller pool of taxable workers to pay for the expanding social programs.

Immigration came to the rescue, and we became adept at recruiting a surplus population of young, skilled, economically focused migrants seeking their fortune abroad. The many newcomers meant a growing population and with it a larger tax base.

But what would happen if Canada could no longer depend on a steady influx of newcomers? The short answer is that our population would shrink, and our welfare state would come under intolerable strain. The long answer is that Canadian businesses, which have become addicted to abundant, cheap foreign labour through the Temporary Foreign Worker Program, would be obliged to invest in hiring, training and retaining Canadian workers.

Provincial and federal governments would scramble to keep older Canadians in the workforce for longer. And governments would be torn between demands to cut the welfare state or privatize large parts of it while raising taxes to help pay for it.

No matter what, the status quo won’t continue. And – even though Canada is right now taking in record numbers of new immigrants and temporary workers – we are going to discover this soon. The main cause is the “peak humanity” that I mentioned before. Fertility rates are falling rapidly nearly everywhere. In the industrialized West, births have fallen further in some places than in others, but all countries are now below replacement levels

(except Israel, which was at 2.9 in 2020).

Deaths have long been outpacing births in China, Japan and some Western countries like Italy. A recent study in The Lancet expects that by 2100, 97 percent of countries will be shrinking. Only Western and Eastern sub-Saharan Africa will have birth rates above replacement levels, though births will be falling in those regions also.

In a world of sub-replacement fertility, there will still be well-educated, highly skilled people abroad. But there will not be a surplus of them. Some may still be ready and willing to put down roots in Canada, but the number will soon be both small and dwindling. And it seems likely that countries which have produced Canada’s immigrants in recent years will try hard to retain domestic talent as their own populations decline. In contrast, the population of sub-Saharan Africa will be growing for a little longer. But unless education and skills-training change drastically in that region, countries there will not produce the kind of skilled immigrants that Canada has come to rely on.

And so the moment is rapidly approaching when immigration will no longer be able to make up for falling Canadian fertility. Governments will have to confront the problem directly—not years or decades hence, but now.

While many will cite keeping the welfare state solvent as the driving force, in my view this is not the reason to do it. The reason to do it is that it is in Canada’s national interest to make it easier for families to have the number of children that they want. A 2023 study by the think-tank Cardus found that nearly half of Canadian women at the end of their reproductive years had fewer children than they had wanted. This amounted to an average

of 0.5 fewer children per woman – a shortfall that would lift Canada close to replacement level.

The United Nations Population Fund (UNPF) has noticed the same challenge on a global scale. Neither Cardus nor the UNPF prescribes any specific solutions, but their analysis points to the same thing: public policy should focus on identifying and removing barriers families face to having the number of children they want.

Every future government should be vigilant against impediments to family-formation and raising a desired number of children. Making housing more abundant and affordable would surely be a good beginning. Better planning must go into making livable communities (not merely atomized dwellings) with infrastructure favouring families and designed to ease commuting. But more fundamentally, policy-makers will need to ask and answer an uncomfortable question: why did we allow barriers to fertility to arise in the first place?

The original, full-length version of this article was recently published in C2C Journal.

Michael Bonner is a political consultant with Atlas Strategic Advisors, LLC, contributing editor to the Dorchester Review, and author of In Defense of Civilization: How Our Past Can Renew Our Present.

Business

National dental program likely more costly than advertised

From the Fraser Institute

By Matthew Lau

At the beginning of June, the Canadian Dental Care Plan expanded to include all eligible adults. To be eligible, you must: not have access to dental insurance, have filed your 2024 tax return in Canada, have an adjusted family net income under $90,000, and be a Canadian resident for tax purposes.

As a result, millions more Canadians will be able to access certain dental services at reduced—or no—out-of-pocket costs, as government shoves the costs onto the backs of taxpayers. The first half of the proposition, accessing services at reduced or no out-of-pocket costs, is always popular; the second half, paying higher taxes, is less so.

A Leger poll conducted in 2022 found 72 per cent of Canadians supported a national dental program for Canadians with family incomes up to $90,000—but when asked whether they would support the program if it’s paid for by an increase in the sales tax, support fell to 42 per cent. The taxpayer burden is considerable; when first announced two years ago, the estimated price tag was $13 billion over five years, and then $4.4 billion ongoing.

Already, there are signs the final cost to taxpayers will far exceed these estimates. Dr. Maneesh Jain, the immediate past-president of the Ontario Dental Association, has pointed out that according to Health Canada the average patient saved more than $850 in out-of-pocket costs in the program’s first year. However, the Trudeau government’s initial projections in the 2023 federal budget amounted to $280 per eligible Canadian per year.

Not all eligible Canadians will necessarily access dental services every year, but the massive gap between $850 and $280 suggests the initial price tag may well have understated taxpayer costs—a habit of the federal government, which over the past decade has routinely spent above its initial projections and consistently revises its spending estimates higher with each fiscal update.

To make matters worse there are also significant administrative costs. According to a story in Canadian Affairs, “Dental associations across Canada are flagging concerns with the plan’s structure and sustainability. They say the Canadian Dental Care Plan imposes significant administrative burdens on dentists, and that the majority of eligible patients are being denied care for complex dental treatments.”

Determining eligibility and coverage is a huge burden. Canadians must first apply through the government portal, then wait weeks for Sun Life (the insurer selected by the federal government) to confirm their eligibility and coverage. Unless dentists refuse to provide treatment until they have that confirmation, they or their staff must sometimes chase down patients after the fact for any co-pay or fees not covered.

Moreover, family income determines coverage eligibility, but even if patients are enrolled in the government program, dentists may not be able to access this information quickly. This leaves dentists in what Dr. Hans Herchen, president of the Alberta Dental Association, describes as the “very awkward spot” of having to verify their patients’ family income.

Dentists must also try to explain the program, which features high rejection rates, to patients. According to Dr. Anita Gartner, president of the British Columbia Dental Association, more than half of applications for complex treatment are rejected without explanation. This reduces trust in the government program.

Finally, the program creates “moral hazard” where people are encouraged to take riskier behaviour because they do not bear the full costs. For example, while we can significantly curtail tooth decay by diligent toothbrushing and flossing, people might be encouraged to neglect these activities if their dental services are paid by taxpayers instead of out-of-pocket. It’s a principle of basic economics that socializing costs will encourage people to incur higher costs than is really appropriate (see Canada’s health-care system).

At a projected ongoing cost of $4.4 billion to taxpayers, the newly expanded national dental program is already not cheap. Alas, not only may the true taxpayer cost be much higher than this initial projection, but like many other government initiatives, the dental program already seems to be more costly than initially advertised.

-

Agriculture1 day ago

Agriculture1 day agoCanada’s supply management system is failing consumers

-

Alberta18 hours ago

Alberta18 hours agoAlberta uncorks new rules for liquor and cannabis

-

Crime19 hours ago

Crime19 hours agoProject Sleeping Giant: Inside the Chinese Mercantile Machine Linking Beijing’s Underground Banks and the Sinaloa Cartel

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoPrairie provinces and Newfoundland and Labrador see largest increases in size of government

-

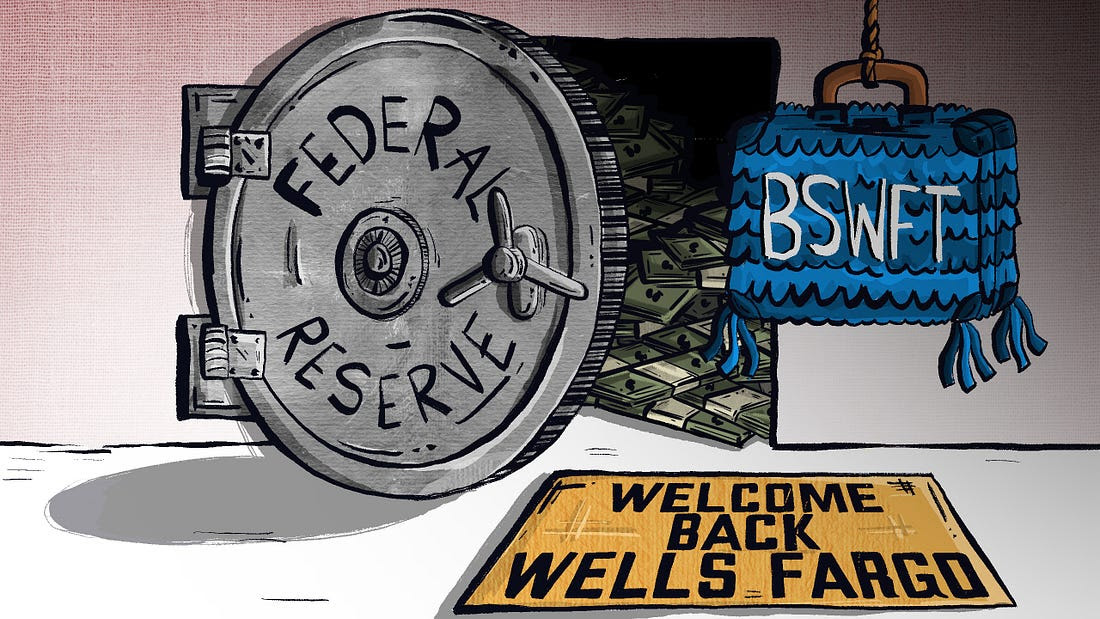

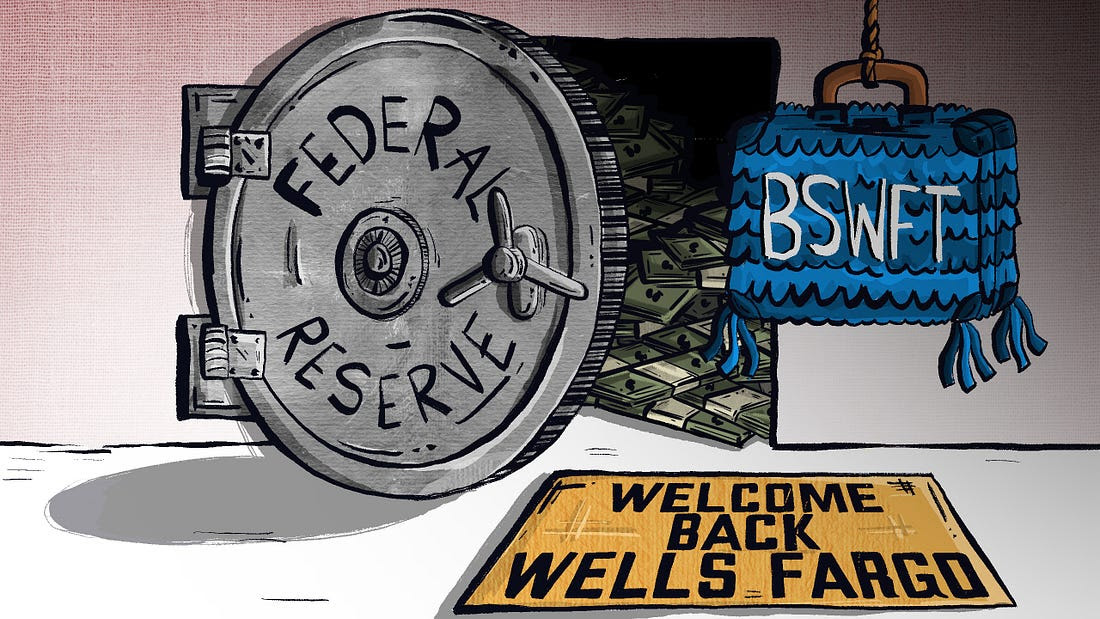

Banks2 days ago

Banks2 days agoWelcome Back, Wells Fargo!

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoWoman wins settlement after YMCA banned her for complaining about man in girls’ locker room

-

Economy1 day ago

Economy1 day agoTrump opens door to Iranian oil exports

-

International10 hours ago

International10 hours agoTrump transportation secretary tells governors to remove ‘rainbow crosswalks’