armed forces

We are witnessing the future of war on the battlefields of Ukraine

From the MacDonald Laurier Institute

By Richard Shimooka

We would be wise to learn the lessons the Ukrainians have fought so hard to learn

Historically, certain wars have stimulated the development of future defence thinking. The 1905 Russo-Japanese War previewed many features of the Great War a decade later, including the lethality of machine guns and howitzers, as well as the ubiquity of trench warfare. The 1973 Yom Kippur War between Israel and its Arab Neighbours was particularly influential for present wars—the Arab combatants’ use of new anti-tank guided missiles challenged many existing doctrines. This is not to say that all groups absorb the lessons directly or effectively. Many of the great powers, including Russia (who fought in the 1905 war), failed to adopt the lessons laid bare in that conflict and suffered grievous casualties in the first years of World War I as a result.

Approaching two years since the invasion, the war in Ukraine has the potential to have an outside impact on the future of war for a variety of reasons. Its timing comes as a number of new technologies have emerged, many of which have come from the civilian space. These include the proliferation of drones, low-cost satellites, and high bandwidth networking—all of which to date have had major effects on the outcome of the war.1 Over the past two years, both sides have adapted their doctrine and capabilities to reflect a cycle of learning and adaptation which gives a clearer understanding of where these technologies are headed.

Some of these trends are a validation of overriding trends in warfare, particularly around the collection and use of data afforded by networked systems. This is evident in the maturation of the “reconnaissance-strike” complexes in Russian and Ukrainian doctrine. Essentially, this is a streamlining of the process of identifying and attacking targets with precision fire, usually from some form of artillery. The United States and NATO have been pursuing a roughly similar—but much more advanced and all-encompassing—concept known as “multi-domain operations.” There are several common denominators between both doctrines, including the effort to expand detection over wider areas, as well as hastening the decision-making process which can improve the lethality of any weapon system attached to it. While it may not be able to employ traditional airpower, the use of long-range artillery (including the recently provided ATACMS missile system) shows the effectiveness of this approach to war. It also allows for a greater economy of force—a critical consideration for Ukraine due to its disadvantageous economic and strategic situation facing a state three times its size.

A key feature of progress in this area is its organic nature. Since the start of direct hostilities in 2014, Ukraine has done well to build up some of these connective capabilities adapting civilian systems for military purposes, such as the Starlink satellite network and apps for mobile devices. A large portion are ground-up approaches, developed even by military units to suit their particular operational needs. This was part of the total war approach that the Ukrainian government has instituted, often leveraging their emerging tech industries to develop new capabilities to fight against the Russian Federation. Many allies have similar efforts, but too often focus remains on a very centralized, top-down approach, which has led to substandard outcomes. Some balance between the two poles is likely ideal.

Another major consideration is the revolutionary impact of drones on air warfare. Traditional manned airpower, like F-16, Mig-29s, and even attack helicopters, remain as relevant as ever in Ukraine. While no side possesses true air superiority, some localized control has been established for short periods, resulting in potentially decisive consequences. However, the war has followed the trend of other recent wars with low-cost, attritable drones playing an important role. While this has been evident in the strike-reconnaissance doctrine discussed above, the so-called kamikaze loitering drones, such as the Russian Lancet and armed first-person view commercial drones, have played an important role as well.

One important aspect is what is known as the “mass” of these capabilities—not individually, but as a collective system or swarm of multiple individual units that can be lost without a major degradation of their lethality. At present, the link between traditional and emerging airpower domains is fairly disjointed over the battlefield in Ukraine, perhaps due to lingering service parochialism. But once combined they will only multiply each other’s lethality.

There is, however, one question concerning this new frontier of airpower’s ultimate influence in the future. It hinges significantly on the efficacy of new anti-drone systems, like those being developed by the United States Army and NATO allies. These potentially may blunt or even remove the deadly threat these UAVs pose to modern ground forces. But as of now they are in their infancy and very few are present in Ukraine today. If they are unable to make a major impact, then the future of conflict will be radically different.

Over the past thirty years, Canada, the United States, and its allies have often been able to deploy troops abroad to many stabilization and peacekeeping missions, in part due to the relatively benign threat environment they were entering. There was confidence that deployed soldiers would not incur significant casualties, which would arouse domestic opposition to the missions themselves. If the lethality of these unmanned drone systems remains unchecked, then, considering their greater ubiquity, it may drastically constrain the ability of Western countries to intervene and assert their muscle abroad, even in low-risk environments.

Finally, and perhaps most critically, is the need for an adaptive defence industrial base (another word for military supply chains) with the capacity to meet a wide need for war. The Russian Federation, for example, faced wide-ranging and intrusive sanctions from the start of the conflict that precluded them from obtaining a number of key resources for their war effort, ranging from raw materials to advanced technology components. They have been able to weather these challenges due to a combination of factors: a deliberate effort to develop an autarkic industrial base that started after 2014, a less technologically advanced military, and sanctions-avoiding policies such as smuggling and diversifying their foreign supplier base to more reliable allies.

While Western allies are unlikely to face the same restrictions in a potential future conflict on the scale that Russia has, in some ways they have greater challenges. These countries rely on much more sophisticated military capabilities that have levels of complexity far in excess of Russian systems. The sheer diversity in all of the raw materials inputs and various subcomponent providers, as well as the networks to make them all work, means that they are actually much easier to disrupt. Shades of this were evident during the initial months of the COVID-19 epidemic when the production of civilian goods was affected by shortages and supply chain disruptions.

Furthermore, underinvestment in the defence industrial base has left the capacity to ramp up production in most areas perilously slow, even two years after the conflict started.

More effort must be spent on creating a much more resilient industrial base that has the capacity to ramp up production to meet the needs of modern war. This requires significant front-end investment by governments in capacity building as no private firm is willing to spend money in that fashion without any guarantee of a return. At the same time, building capacity must be targeted and appropriate to the actual needs of Canada and its allies—taking lessons from Ukraine without understanding their context would be a mistake. That war and its material demands are unique to it.2 Discerning the actual needs and developing accordingly should be done through careful analysis and wargaming, much like the recent Center for Strategic International Studies analysis on U.S. missile needs in a potential war against China has done.

In the end, a clear trend that seems to bind all of these areas is the need for adaptability and critical thinking. Warfare is fast becoming more lethal and decisive. Modern armies must be able to respond to those changes as quickly as they occur—or better yet, lead those changes against their adversaries. That, for one, cannot occur in an organization that is continually starved for funding like the Canadian Armed Forces is today.

But it may also require a radical reorganization and re-think of how defence policy, strategy, operations, and doctrine are developed and implemented—not to mention personnel and industrial policy. As the conflict in Ukraine has laid bare, bringing in the brightest minds and giving them greater leeway to develop responses is key, as is harnessing the potential and building the capacity of domestic industrial bases. These are essential and urgent lessons we must learn. They have been hard won by the sacrifices of the Ukrainian people for our benefit. It would be a shame to waste them.

Richard Shimooka is a Hub contributing writer and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute who writes on defence policy.

armed forces

Canada’s first ‘transgender’ military chaplain suspended for alleged sexual harassment

From LifeSiteNews

Canadian Armed Forces Captain ‘Beatrice’ Gale reportedly sought to grope a male soldier while drunk and was suspended just a few weeks after the Canadian military promoted him for ‘International Transgender Day of Visibility.’

Canadian Department of National Defence has suspended a “transgender” military chaplain it previously celebrated after he reportedly sought to grope a male soldier at the Royal Military College while drunk.

On March 28, the government highlighted Canadian Armed Forces Captain “Beatrice” Gale, a man who “identifies” as a woman, for “International Transgender Day of Visibility.” The military’s “first openly transgender chaplain” has been “a vocal advocate” for the so-called “rights” of transgender-identifying members, according to the press release, resulting “in policy changes that contributed to more inclusive gender-affirming medical care for CAF members.”

“I hope that being a transgender chaplain [sic] sends a message to the 2SLGBTQI+ community that the Royal Canadian Chaplain Service cares,” he said. “That it cares for that community.”

Just weeks later, however, the chaplain is generating a different kind of publicity.

True North reports that Gale’s chaplaincy has been revoked following a hearing finding he made an “inappropriate comment or request to another individual.”

Gale was determined to have violated the Queen’s Regulations and Orders by “behav[ing] in a manner that adversely affects the discipline, efficiency or morale of the Canadian Forces.” The specific details of the offense have not been officially confirmed, but, according to an anonymous source, he became inebriated at dinner and asked to grope a male lieutenant’s buttocks.

“The mandate for Captain Gale to serve as a Canadian military chaplain remains suspended. The Chaplain General will consider the implications of the summary hearing’s outcome to determine if additional administrative actions within their authority are required,” said DND spokesperson Andrée-Anne Poulin. Gale was docked two days pay and 20 days leave and is currently on administrative duty.

“If a male officer behaved in a similar manner towards a subordinate female, the situation would be dealt with differently, and the offender’s name would be leaked to the press. Unfortunately, there is a lack of equality in how the Canadian Armed Forces handle such allegations,” attorney Phillip Millar, a former combat officer who now represents Canadian soldiers, told True North.

He added that he once had a client who “was not granted the same leniency for much less serious alleged infractions. However, in the case of a transgender offender who held a position of trust as a padre and a senior in rank, the matter was simply swept under the rug.”

As is the case in the United States, Canada’s armed forces are currently struggling to attract recruits in the wake of adopting “woke” policies such as COVID-19 shot mandates, “climate change” lectures, and pro-LGBT “identity” initiatives.

The DND declared last month that increased “diversity and inclusivity” are “vital” to creating an effective military and that they “enrich the workplace.”

armed forces

Canadians are finally waking up to the funding crisis that’s sent the Canadian Armed Forces into a “death spiral”

From the Macdonald Laurier Institute

By By J.L. Granatstein

Must we wait for Trump to attack free trade between Canada and the US before our politicians get the message that defence matters to Washington?

Nations have interests – national interests – that lay out their ultimate priorities. The first one for every country is to protect its population and territory. It is sometimes hard to tell, but this also applies to Canada. Ottawa’s primary job is to make sure that Canada and Canadians are safe. And Canada also has a second priority: to work with our allies to protect their and our freedom. As we share this continent with the United States, this means that we must pay close attention to our neighbouring superpower.

Regrettably for the last six decades or so we have not done this very well. During the 1950s, the Liberal government of Louis St. Laurent in some years spent more than 7 percent of GDP on defence, making Canada the most militarily credible of the middle powers. His successors whittled down defence spending and cut the numbers of troops, ships, and aircraft. By the end of the Cold War, in the early 1990s, our forces had shrunk, and their equipment was increasingly obsolescent.

Another Liberal prime minister, Jean Chrétien, balanced the budget in 1998 by slashing the military even more, and by getting rid of most of the procurement experts at the Department of National Defence, he gave us many of the problems the Canadian Armed Forces face today. Canadians and their governments wanted social security measures, not troops with tanks, and they got their wish.

There was another factor of significant importance, though it is one usually forgotten. Lester Pearson’s Nobel Peace Prize for helping to freeze the Suez Crisis of 1956 convinced Canadians that they were natural-born peacekeepers. Give a soldier a blue beret and an unloaded rifle and he could be the representative of Canada as the moral superpower we wanted to be. The Yanks fought wars, but Canada kept the peace, or so we believed, and Canada for decades had servicemen and women in every peacekeeping operation.

There were problems with this. First, peacekeeping didn’t really work that well. It might contain a conflict, but it rarely resolved one – unless the parties to the dispute wanted peace. In Cyprus, for example, where Canadians served for three decades, neither the Greek- or Turkish-Cypriots wanted peace; nor did their backers in Athens and Ankara. The Cold War’s end also unleashed ethnic nationalisms, and Yugoslavia, for one, fractured into conflicts between Serbs, Croats, Bosnians, Christians, and Muslims, leading to all-out war. Peacekeepers tried to hold the lid on, but it took NATO to bash heads to bring a truce if not peace.

And there was a particular Canadian problem with peacekeeping. If all that was needed was a stock of blue berets and small arms, our governments asked, why spend vast sums on the military? Peacekeeping was cheap, and this belief sped up the budget cuts.

Even worse, the public believed the hype and began to resist the idea that the Canadian Armed Forces should do anything else. For instance, the Chrétien government took Canada into Afghanistan in 2001 to participate in what became a war to dislodge the Taliban, but huge numbers of Canadians believed that this was really only peacekeeping with a few hiccups.

Stephen Harper’s Conservative government nonetheless gave the CAF the equipment it needed to fight in Afghanistan, and the troops did well. But the casualties increased as the fighting went on, and Harper pulled Canada out of the conflict well before the Taliban seized power again in 2021.

Harper’s successor, Liberal Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, clearly has no interest in the military except as a somewhat rogue element that needs to be tamed, made comfortable for its members, and to act as a social laboratory with quotas for visible minorities and women.

Is this an exaggeration? This was Trudeau’s mandate letter to his defence minister in December 2021: “Your immediate priority is to take concrete steps to build an inclusive and diverse Defence Team, characterized by a healthy workplace free from harassment, discrimination, sexual misconduct, and violence.” DND quickly permitted facial piercings, coloured nail polish, beards, long hair, and, literally, male soldiers in skirts, so long as the hem fell below the knees. This was followed by almost an entire issue of the CAF’s official publication, Canadian Military Journal, devoted to culture change in the most extreme terms. You can’t make this stuff up.

Thus, our present crisis: a military short some 15,000 men and women, with none of the quotas near being met. A defence minister who tells a conference the CAF is in a “death spiral” because of its inability to recruit soldiers. (Somehow no one in Ottawa connects the culture change foolishness to a lack of recruits.) Fighter pilots, specialized sailors, and senior NCOs, their morale broken, taking early retirement. Obsolete equipment because of procurement failures and decade-long delays. Escalating costs for ships, aircraft, and trucks because every order requires that domestic firms get their cut, no matter if that hikes prices even higher. The failure to meet a NATO accord, agreed to by Canada, that defence spending be at least 2 percent of GDP, and no prospect that Canada will ever meet this threshold.

But something has changed.

Three opinion polls at the beginning of March all reported similar results: the Canadian public – worried about Russia and Putin’s war against Ukraine, and anxious about China, North Korea, and Iran (all countries with undemocratic regimes and, Iran temporarily excepted, nuclear weapons) – has noticed at last that Canada is unarmed and undefended. Canadians are watching with concern as Ottawa is scorned by its allies in NATO, Washington, and the Five Eyes intelligence sharing alliance.

At the same time, official Department of National Defence documents laid out the alarming deficiencies in the CAF’s readiness: too few soldiers ready to respond to crises and not enough equipment that is in working order for those that are ready.

The bottom line? Canadians finally seem willing to accept more spending on defence.

The media have been hammering at the government’s shortcomings. So have retired generals. General Rick Hillier, the former chief of the defence staff, was especially blunt: “[The CAF’s] equipment has been relegated to sort-of-broken equipment parked by the fence. Our fighting ships are on limitations to the speed that they can sail or the waves that they can sail in. Our aircraft, until they’re replaced, they’re old and sort of not in that kind of fight anymore. And so, I feel sorry for the men and women who are serving there right now.”

The Trudeau government has repeatedly demonstrated that it simply does not care. It offers more money for the CBC and for seniors’ dental care, pharmaceuticals, and other vote-winning objectives, but nothing for defence (where DND’s allocations astonishingly have been cut by some $1 billion this year and at least the next two years). There is no hope for change from the Liberals, their pacifistic NDP partners, or from the Bloc Québécois.

The Conservative Party, well ahead in the polls, looks to be in position to form the next government. What will they do for the military? So far, we don’t know – Pierre Poilievre has been remarkably coy. The Conservative leader has said he wants to cut wasteful spending and eliminate foreign aid to dictatorial regimes and corrupted UN agencies like UNRWA. He says he will slash the bureaucracy and reform the procurement shambles in Ottawa, and he will “work towards” spending on the CAF to bring us to the equivalent of 2 percent of GDP. His staff say that Poilievre is not skeptical about the idea of collective security and NATO; rather, he is committed to balancing the books.

What this all means is clear enough. No one should expect that a Conservative government will move quickly to spend much more on defence than the Grits. A promise to “work towards” 2 percent is not enough, and certainly not if former US President Donald Trump ends up in the White House again. Must we wait for Trump to attack free trade between Canada and the US before our politicians get the message that defence matters to Washington? Unfortunately, it seems so, and Canadians will not be able to say that they weren’t warned. After all, it should be obvious that it is in our national interest to protect ourselves.

J.L. Granatstein taught Canadian history, was Director and CEO of the Canadian War Museum, and writes on military and political history. His most recent book is Canada’s Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace. (3rd edition).

-

COVID-192 days ago

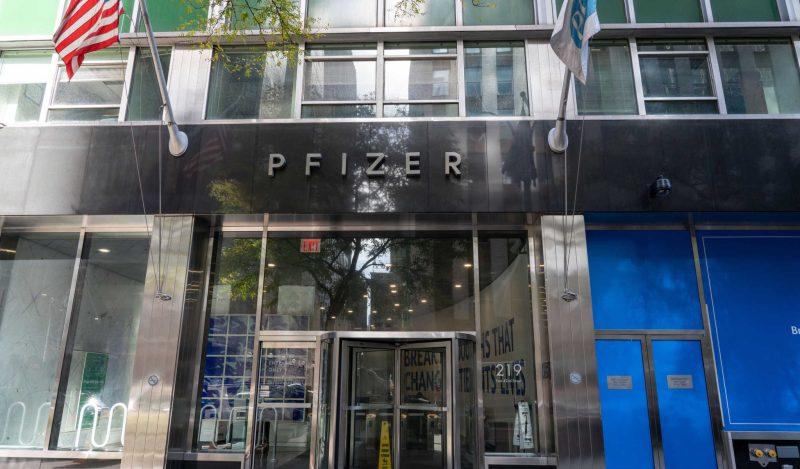

COVID-192 days agoPfizer reportedly withheld presence of cancer-linked DNA in COVID jabs from FDA, Health Canada

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoTrudeau gov’t has paid out over $500k to employees denied COVID vaccine mandate exemptions

-

National2 days ago

National2 days agoAnger towards Trudeau government reaches new high among Canadians: poll

-

Automotive5 hours ago

Automotive5 hours agoThe EV ‘Bloodbath’ Arrives Early

-

Addictions1 day ago

Addictions1 day agoWhy can’t we just say no?

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoRFK Jr tells EWTN: Politicization of the CIA, FBI, Secret Service under Biden is ‘very troubling’

-

Brownstone Institute2 days ago

Brownstone Institute2 days agoThe Teams Are Set for World War III

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoThe Climate-Alarmist Movement Has A Big PR Problem On Its Hands