Alberta

US approves chicken made from cultivated cells, the nation’s first ‘lab-grown’ meat

For the first time, U.S. regulators on Wednesday approved the sale of chicken made from animal cells, allowing two California companies to offer “lab-grown” meat to the nation’s restaurant tables and eventually, supermarket shelves.

The Agriculture Department gave the green light to Upside Foods and Good Meat, firms that had been racing to be the first in the U.S. to sell meat that doesn’t come from slaughtered animals — what’s now being referred to as “cell-cultivated” or “cultured” meat as it emerges from the laboratory and arrives on dinner plates.

The move launches a new era of meat production aimed at eliminating harm to animals and drastically reducing the environmental impacts of grazing, growing feed for animals and animal waste.

“Instead of all of that land and all of that water that’s used to feed all of these animals that are slaughtered, we can do it in a different way,” said Josh Tetrick, co-founder and chief executive of Eat Just, which operates Good Meat.

The companies received approvals for federal inspections required to sell meat and poultry in the U.S. The action came months after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration deemed that products from both companies are safe to eat. A manufacturing company called Joinn Biologics, which works with Good Meat, was also cleared to make the products.

Cultivated meat is grown in steel tanks, using cells that come from a living animal, a fertilized egg or a special bank of stored cells. In Upside’s case, it comes out in large sheets that are then formed into shapes like chicken cutlets and sausages. Good Meat, which already sells cultivated meat in Singapore, the first country to allow it, turns masses of chicken cells into cutlets, nuggets, shredded meat and satays.

But don’t look for this novel meat in U.S. grocery stores anytime soon. Cultivated chicken is much more expensive than meat from whole, farmed birds and cannot yet be produced on the scale of traditional meat, said Ricardo San Martin, director of the Alt:Meat Lab at University of California Berkeley.

The companies plan to serve the new food first in exclusive restaurants: Upside has partnered with a San Francisco restaurant called Bar Crenn, while Good Meat dishes will be served at a Washington, D.C., restaurant run by chef and owner Jose Andrés.

Company officials are quick to note the products are meat, not substitutes like the Impossible Burger or offerings from Beyond Meat, which are made from plant proteins and other ingredients.

Globally, more than 150 companies are focusing on meat from cells, not only chicken but pork, lamb, fish and beef, which scientists say has the biggest impact on the environment.

Upside, based in Berkeley, operates a 70,000-square-foot building in nearby Emeryville. On a recent Tuesday, visitors entered a gleaming commercial kitchen where chef Jess Weaver was sauteeing a cultivated chicken filet in a white wine butter sauce with tomatoes, capers and green onions.

The finished chicken breast product was slightly paler than the grocery store version. Otherwise it looked, cooked, smelled and tasted like any other pan-fried poultry.

“The most common response we get is, ‘Oh, it tastes like chicken,’” said Amy Chen, Upside’s chief operating officer.

Good Meat, based in Alameda, operates a 100,000-square-foot plant, where chef Zach Tyndall dished up a smoked chicken salad on a sunny June afternoon. He followed it with a chicken “thigh” served on a bed of potato puree with a mushroom-vegetable demi-glace and tiny purple cauliflower florets. The Good Meat chicken product will come pre-cooked, requiring only heating to use in a range of dishes.

Chen acknowledged that many consumers are skeptical, even squeamish, about the thought of eating chicken grown from cells.

“We call it the ‘ick factor,’” she said.

The sentiment was echoed in a recent poll conducted by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. Half of U.S. adults said that they are unlikely to try meat grown using cells from animals. When asked to choose from a list of reasons for their reluctance, most who said they’d be unlikely to try it said “it just sounds weird.” About half said they don’t think it would be safe.

But once people understand how the meat is made, they’re more accepting, Chen said. And once they taste it, they’re usually sold.

“It is the meat that you’ve always known and loved,” she said.

Cultivated meat begins with cells. Upside experts take cells from live animals, choosing those most likely to taste good and to reproduce quickly and consistently, forming high-quality meat, Chen said. Good Meat products are created from a master cell bank formed from a commercially available chicken cell line.

Once the cell lines are selected, they’re combined with a broth-like mixture that includes the amino acids, fatty acids, sugars, salts, vitamins and other elements cells need to grow. Inside the tanks, called cultivators, the cells grow, proliferating quickly. At Upside, muscle and connective tissue cells grow together, forming large sheets. After about three weeks, the sheets of poultry cells are removed from the tanks and formed into cutlets, sausages or other foods. Good Meat cells grow into large masses, which are shaped into a range of meat products.

Both firms emphasized that initial production will be limited. The Emeryville facility can produce up to 50,000 pounds of cultivated meat products a year, though the goal is to expand to 400,000 pounds per year, Upside officials said. Good Meat officials wouldn’t estimate a production goal.

By comparison, the U.S. produces about 50 billion pounds of chicken per year.

It could take a few years before consumers see the products in more restaurants and seven to 10 years before they hit the wider market, said Sebastian Bohn, who specializes in cell-based foods at CRB, a Missouri firm that designs and builds facilities for pharmaceutical, biotech and food companies.

Cost will be another sticking point. Neither Upside nor Good Meat officials would reveal the price of a single chicken cutlet, saying only that it’s been reduced by orders of magnitude since the firms began offering demonstrations. Eventually, the price is expected to mirror high-end organic chicken, which sells for up to $20 per pound.

San Martin said he’s concerned that cultivated meat may wind up being an alternative to traditional meat for rich people, but will do little for the environment if it remains a niche product.

“If some high-end or affluent people want to eat this instead of a chicken, it’s good,” he said. “Will that mean you will feed chicken to poor people? I honestly don’t see it.”

Tetrick said he shares critics’ concerns about the challenges of producing an affordable, novel meat product for the world. But he emphasized that traditional meat production is so damaging to the planet it requires an alternative — preferably one that doesn’t require giving up meat all together.

“I miss meat,” said Tetrick, who grew up in Alabama eating chicken wings and barbecue. “There should be a different way that people can enjoy chicken and beef and pork with their families.”

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Jonel Aleccia And Laura Ungar, The Associated Press

Alberta

‘Weird and wonderful’ wells are boosting oil production in Alberta and Saskatchewan

From the Canadian Energy Centre

Multilateral designs lift more energy with a smaller environmental footprint

A “weird and wonderful” drilling innovation in Alberta is helping producers tap more oil and gas at lower cost and with less environmental impact.

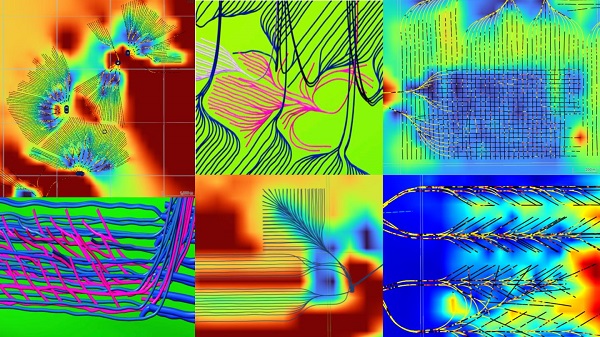

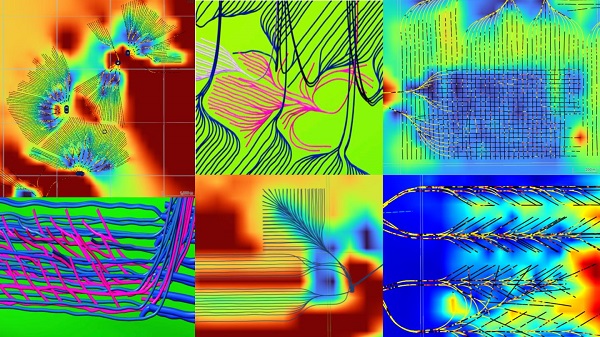

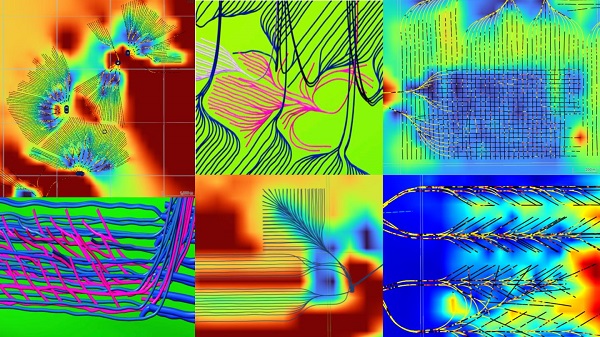

With names like fishbone, fan, comb-over and stingray, “multilateral” wells turn a single wellbore from the surface into multiple horizontal legs underground.

“They do look spectacular, and they are making quite a bit of money for small companies, so there’s a lot of interest from investors,” said Calin Dragoie, vice-president of geoscience with Calgary-based Chinook Consulting Services.

Dragoie, who has extensively studied the use of multilateral wells, said the technology takes horizontal drilling — which itself revolutionized oil and gas production — to the next level.

“It’s something that was not invented in Canada, but was perfected here. And it’s something that I think in the next few years will be exported as a technology to other parts of the world,” he said.

Dragoie’s research found that in 2015 less than 10 per cent of metres drilled in Western Canada came from multilateral wells. By last year, that share had climbed to nearly 60 per cent.

Royalty incentives in Alberta have accelerated the trend, and Saskatchewan has introduced similar policy.

Multilaterals first emerged alongside horizontal drilling in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Dragoie said. But today’s multilaterals are longer, more complex and more productive.

The main play is in Alberta’s Marten Hills region, where producers are using multilaterals to produce shallow heavy oil.

Today’s average multilateral has about 7.5 horizontal legs from a single surface location, up from four or six just a few years ago, Dragoie said.

One record-setting well in Alberta drilled by Tamarack Valley Energy in 2023 features 11 legs stretching two miles each, for a total subsurface reach of 33 kilometres — the longest well in Canada.

By accessing large volumes of oil and gas from a single surface pad, multilaterals reduce land impact by a factor of five to ten compared to conventional wells, he said.

The designs save money by skipping casing strings and cement in each leg, and production is amplified as a result of increased reservoir contact.

Here are examples of multilateral well design. Images courtesy Chinook Consulting Services.

Parallel

Fishbone

Fan

Waffle

Stingray

Frankenwells

Alberta

Alberta to protect three pro-family laws by invoking notwithstanding clause

From LifeSiteNews

Premier Danielle Smith said her government will use a constitutional tool to defend a ban on transgender surgery for minors and stopping men from competing in women’s sports.

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith said her government will use a rare constitutional tool, the notwithstanding clause, to ensure three bills passed this year — a ban on transgender surgery for minors, stopping men from competing in women’s sports, and protecting kids from extreme aspects of the LGBT agenda — stand and remain law after legal attacks from extremist activists.

Smith’s United Conservative Party (UCP) government stated that it will utilize a new law, Bill 9, to ensure that laws passed last year remain in effect.

“Children deserve the opportunity to grow into adulthood before making life-altering decisions about their gender and fertility,” Smith said in a press release sent to LifeSiteNews and other media outlets yesterday.

“By invoking the notwithstanding clause, we’re ensuring that laws safeguarding children’s health, education and safety cannot be undone – and that parents are fully involved in the major decisions affecting their children’s lives. That is what Albertans expect, and that is what this government will unapologetically defend.”

Alberta Justice Minister and Attorney General Mickey Amery said that the laws passed last year are what Albertans voted for in the last election.

“These laws reflect an overwhelming majority of Albertans, and it is our responsibility to ensure that they will not be overturned or further delayed by activists in the courts,” he noted.

“The notwithstanding clause reinforces democratic accountability by keeping decisions in the hands of those elected by Albertans. By invoking it, we are providing certainty that these protections will remain in place and that families can move forward with clarity and confidence.”

The Smith government said the notwithstanding clause will apply to the following pieces of legislation:

-

Bill 26, the Health Statutes Amendment Act, 2024, prohibits both gender reassignment surgery for children under 18 and the provision of puberty blockers and hormone treatments for the purpose of gender reassignment to children under 16.

-

Bill 27, the Education Amendment Act, 2024, requires schools to obtain parental consent when a student under 16 years of age wishes to change his or her name or pronouns for reasons related to the student’s gender identity, and requires parental opt-in consent to teaching on gender identity, sexual orientation or human sexuality.

-

Bill 29, the Fairness and Safety in Sport Act, requires the governing bodies of amateur competitive sports in Alberta to implement policies that limit participation in women’s and girls’ sports to those who were born female.”

Bill 26 was passed in December of 2024, and it amends the Health Act to “prohibit regulated health professionals from performing sex reassignment surgeries on minors.”

As reported by LifeSiteNews, pro-LGBT activist groups, with the support of Alberta’s opposition New Democratic Party (NDP), have tried to stop the bill via lawsuits. It prompted the Smith government to appeal a court injunction earlier this year blocking the province’s ban on transgender surgeries and drugs for gender-confused minors.

Last year, Smith’s government also passed Bill 27, a law banning schools from hiding a child’s pronoun changes at school that will help protect kids from the extreme aspects of the LGBT agenda.

Bill 27 will also empower the education minister to, in effect, stop the spread of extreme forms of pro-LGBT ideology or anything else to be allowed to be taught in schools via third parties.

Bill 29, which became law last December, bans gender-confused men from competing in women’s sports, the first legislation of its kind in Canada. The law applies to all school boards, universities, and provincial sports organizations.

Alberta’s notwithstanding clause is like all other provinces’ clauses and was a condition Alberta agreed to before it signed onto the nation’s 1982 constitution.

It is meant as a check to balance power between the court system and the government elected by the people. Once it is used, as passed in the legislature, a court cannot rule that the “legislation which the notwithstanding clause applies to be struck down based on the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Alberta Bill of Rights, or the Alberta Human Rights Act,” the Alberta government noted.

While Smith has done well on some points, she has still been relatively soft on social issues of importance to conservatives , such as abortion, and has publicly expressed pro-LGBT views, telling Jordan Peterson earlier this year that conservatives must embrace homosexual “couples” as “nuclear families.”

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day ago‘Modern-Day Escobar’: U.S. Says Former Canadian Olympian Ran Cocaine Pipeline with Cartel Protection and a Corrupt Toronto Lawyer

-

Indigenous2 days ago

Indigenous2 days agoTop constitutional lawyer slams Indigenous land ruling as threat to Canadian property rights

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoDemocrats Explicitly Tell Spy Agencies, Military To Disobey Trump

-

National11 hours ago

National11 hours agoPsyop-Style Campaign That Delivered Mark Carney’s Win May Extend Into Floor-Crossing Gambits and Shape China–Canada–US–Mexico Relations

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta on right path to better health care

-

COVID-198 hours ago

COVID-198 hours agoCovid Cover-Ups: Excess Deaths, Vaccine Harms, and Coordinated Censorship

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoALAN DERSHOWITZ: Can Trump Legally Send Troops Into Our Cities? The Answer Is ‘Wishy-Washy’

-

Alberta21 hours ago

Alberta21 hours ago‘Weird and wonderful’ wells are boosting oil production in Alberta and Saskatchewan