Housing

Trudeau’s 2024 budget could drive out investment as housing bubble continues

From LifeSiteNews

By David James

The extent to which the Canadian economy is distorted by a property bubble can be seen by comparing government debt with household debt, with the latter being 130 percent of GDP, nearly twice as much as American households.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s federal government has brought in its 2024 budget, which projects C$53 billion in new spending over the next 5 years. It includes a significant capital gains tax increase, which some are warning will drive away investment, and a plan for more government-controlled public housing.

The Trudeau government is wrestling with a problem that is afflicting most English-speaking economies: how to deal with the consequences of a 20-year house price bubble that has led to deep social divisions, especially between baby boomers and people under 40.

House prices have tripled over the last 20 years on average, fuelled by the combination of aggressive bank lending and, until recently, falling interest rates. Neither is directly controlled by the federal government. There is no avenue to restrict how much banks lend and the Bank of Canada sets interest rates independently.

Accordingly, the Trudeau government is left to tinker at the edges. It will legislate an increase, from one half to two-thirds, in the share of capital gains subject to taxation for annual investment profits greater than C$250,000. The change will apply to individuals, companies and trusts.

Christina Freeland, Canada’s minister for finance, claimed improbably that only 0.13 percent of Canadians with an average income of $1.42 million are expected to pay more income tax on their capital gains in any given year.

That is a dubious forecast. The average house price in Canada 20 years ago was C$241,000; it is now C$719,000. Any Canadians who bought an investment property (family homes are exempt) before about 2015 are likely to have a capital gain larger than C$250,000 should they sell.

The government’s claim that the change will only affect a tiny proportion of Canada’s population is also belied by the government’s own forecast that the tax change will raise over C$20 billion over five years.

The extent to which the Canadian economy is distorted by a property bubble can be seen by comparing government debt with household debt. Canada’s government debt is fairly modest by current international standards: 67.8 percent of GDP in March 2023, down from 73 percent in the previous year. That is about half the U.S. government debt and half the average for G7 countries.

Canada’s budget deficit is also cautious by Western standards. In 2023-24 it was C$40 billion, equivalent to 1.4 percent of GDP. The U.S. budget deficit is currently over 6 percent of GDP.

By contrast Canada’s household debt, inflated by large mortgages, is at over 130 percent of GDP, making borrowers vulnerable to rising interest rates. U.S. household debt is about 75 percent of GDP. Attracted by rising house prices and the advantages of negative gearing (deducting rental losses from a property investment from income tax), Canadians have seen property as their preferred investment option.

Investors account for 30 percent of home buying in Canada, and about one in five properties is owned by an investor. Worse, the enthusiasm for property investment seems to be intensifying. According to one survey, 23 percent of Canadians who do not own a residential investment property say that they are likely to purchase one in the next five years, and 51 percent of current investors say that they are likely to purchase an additional residential investment property within the same time frame.

The problem with the bias towards property investment is that it is actually a punt on land values – and land is inherently unproductive. Business groups have criticized the government’s capital gains hike as a disincentive for investment and innovation, but the far bigger issue is investors’ focus on property, which is crowding out interest in other kinds of investments.

That means the main source investment capital for businesses will tend to come from institutions, such as mutual funds, which typically have a global, rather than local, orientation.

Faced with forces largely out of its control, the Trudeau government is fiddling at the edges. It has announced the introduction of what it calls “Canada’s Housing Plan”, which is aimed at unlocking over 3.8 million homes by 2031. Two million are expected to be new homes, with the government contributing to more than half of them. This will be done by converting underused federal offices into homes, building homes on Canada Post properties, redeveloping National Defence lands, creating more loans for building apartments in Ottawa, and looking at taxing vacant land.

The initiatives may have some effect on supply and demand, but the property price excesses are mainly a financial problem caused by unrestrained bank lending that has been fuelled by low interest rates. When a correction does occur, it will most likely be because of changed global financial conditions, not government policy or fiscal changes.

There are other measures that could be taken to address the property bubble such as reducing, or removing, negative gearing or more heavily taxing capital gains only on property but not other types of investments. But these policies would no doubt would be politically unsalable, so the Trudeau government is instead making minor changes, probably hoping that the problem will fix itself.

Business

A new federal bureaucracy will not deliver the affordable housing Canadians need

Governments are not real estate developers, and Canada should take note of the failure of New Zealand’s cancelled program, highlights a new MEI publication.

“The prospect of new homes is great, but execution is what matters,” says Renaud Brossard, vice president of Communications at the MEI and contributor to the report. “New Zealand’s government also thought more government intervention was the solution, but after seven years, its project had little to show for it.”

During the federal election, Prime Minister Mark Carney promised to establish a new Crown corporation, Build Canada Homes, to act as a developer of affordable housing. His plan includes $25 billion to finance prefabricated homes and an additional $10 billion in low-cost financing for developers building affordable homes.

This idea is not novel. In 2018, the New Zealand government launched the KiwiBuild program to address a lack of affordable housing. Starting with a budget of $1.7 billion, the project aimed to build 100,000 affordable homes by 2028.

In its first year, KiwiBuild successfully completed 49 units, a far cry from the 1,000-home target for that year. Experts estimated that at its initial rate, it would take the government 436 years to reach the 100,000-home target.

By the end of 2024, just 2,389 homes had been built. The program, which was abandoned in October 2024, has achieved barely 3 per cent of its goal, when including units still under construction.

One obstacle for KiwiBuild was how its target was set. The 100,000-home objective was developed with no rigorous process and no consideration for the availability of construction labour, leading to an overestimation of the program’s capabilities.

“What New Zealand’s government-backed home-building program shows is that building homes simply isn’t the government’s expertise,” said Mr. Brossard. “Once again, the source of the problem isn’t too little government intervention; it’s too much.”

According to the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Canada needs an additional 4.8 million homes to restore affordability levels. This would entail building between 430,000 to 480,000 new units annually. Figures on Canada’s housing starts show that we are currently not on track to meet this goal.

The MEI points to high development charges and long permitting delays as key impediments to accelerating the pace of construction.

Between 2020 and 2022 alone, development charges rose by 33 per cent across Canada. In Toronto, these charges now account for more than 25 per cent of the total cost of a home.

Canada also ranks well behind most OECD countries on the time it takes to obtain a construction permit.

“KiwiBuild shows us the limitations of a government-led approach,” said Mr. Brossard. “Instead of creating a whole new bureaucracy, the government should focus on creating a regulatory environment that allows developers to build the housing Canadians need.”

The MEI viewpoint is available here.

* * *

The MEI is an independent public policy think tank with offices in Montreal, Ottawa, and Calgary. Through its publications, media appearances, and advisory services to policymakers, the MEI stimulates public policy debate and reforms based on sound economics and entrepreneurship.

Alberta

Why The Liberal’s Real Estate Economy Could Push Alberta Out of Canada

The real estate maxim goes something like, “Don’t buy the best house on a bad street.” For Albertans smarting from the recent election, that sentiment is starting to gain momentum. Seeing themselves as the credit card for Carney Canada, 47 percent of Albertans recently polled by Leger say they’d consider ending the ties that bind to Eastern Canada.

There are many emotional arguments for the surge from 27 percent pre-election to the current number— starting with unending equalization payments to ungrateful relatives in Quebec and Ontario. Most pertinent to those dismayed by the East’s infatuation with Mike Myers and hockey sweaters is the unsustainable Trudeau Easy Money economy, the real estate bubble that replaced conventional economy since 2015. (Trudeau’s decade left Canada with the lowest GDP in the western world and a $1.26T debt.)

There are now clear signs that the real-estate economy— in the form of condos— created by Trudeau’s post-modern philosophy is about to dive and take with it a good deal of wealth from Canadians and the financial industry. (RBC, the largest lender in Canada just reported $8.94 billion in loans that are unlikely to be paid back, up 13.5% from the first quarter.) And distancing themselves from an unrealized gains tax on principal residences might be a smart move for Alberta and whoever else wants to save their skin.

For the decade before Donald Trump called his bluff, Woke Canada bought Trudeau’s notion you could have wealth without work. The Trudeau notion of an economy was to de-industrialize Canada, resort to “clean” renewable power and live off the equity in Boomers’ homes. Oh, and use billions in tax dollars to push home prices higher for the past 10 years while importing four million new entitled folks.

As Trudeau’s advisor, Mark Carney subscribed to the idea that playing the real-estate game to fund a modern state, the way Albania once based its economy on a lottery. Municipal governments liked the idea of condo financing, because it returned maximum taxation from a small footprint—unlike the cumbersome factories and plants that left for the suburbs.

So they’ve doubled down on real estate while letting traditional industry go to the third world. @MikePMoffatt shows that government taxes and fees add up to $253K on a brand new $1.350M condo in Vancouver, or roughly 19 percent of the price. That $12,000 explains how taxes— and taxes-on-taxes— add over $250K to a Vancouver condo.

This tax hauls why municipalities are pitching hard on multiple-dwelling zoning as a cure-all. No wonder developers in Vancouver are still paying almost double the assessed value for land to build high density housing. In their haste to go big Vancouver realtors are now turning down borderline clients.

But this formula is falling apart. In Toronto, the average monthly rent is now about $2,250. For a condo costing $600K that means’ the investment is $1,800 under water. Little surprise that 20 percent of the city’s condo developments refuse to close. (What has happened to the missing 20 percent? Was it paid off or was it extended in some way?

The economy has seen this bubble coming and yet no one wants to end the party. And that is with tens of thousands of units still to come on stream. You hear stories in the condo/ construction industry in southern Ontario, the Lower Mainland of B.C. and Montreal where a typical builder sold 10 homes in past 12 months compared to the usual 40. Sellers are building exteriors but leaving inside unfinished just to keep crews working.

Some trades say they haven’t worked in a year as the glut suspends work. This is the cost for basing an economy on real-estate speculation. It’s why the Liberals played so hard for the Boomer vote in the election. Calm the aging by protecting the equity built up on their modest homes sitting on valuable property. Which punishes the younger voters who skewed CPC in the election.

While the population booms in Canada and condos sit empty, there remains a dire need for affordable housing in all the main urban markets— including Calgary and Edmonton. But real estate in Canada can’t function based on interest rates over three percent. There is huge political pressure from tax-hungry governments on the Bank of Canada to cut rates. This leads to expectations of 2.79% mortgage rates by the end of 2025.

Mortgage analyst Ron Butler @ronmortgageguy: “From the Feb 2022 peak the regions in Ontario that had the highest run up in 2021 have dropped 17% to 22%. And they will drop some more. We all have begun understand just how big a Catastrophe the 416 Dog Crate Condos have turned into”. (Those who remember the crash of 1980s-1990s have that t-shirt.)

Now replicate the same results across urban Canada. Thousands of owners walking away from underwater mortgages and poorly built homes. While the Big 6 banks can probably sustain writing off that much paper, the smaller funding industry is going to get hammered. Says Butler” “You can’t run 30-year lows in real estate transactions with a 50 percent higher population forever without pressure building from factors like Marriage Breakdown, Old Age & Employment change. But price recovery? More pain coming.

For those who bought the Liberals’ “Change!” Platform as a new economic plan based on frugality and efficiency, guess again. With Parliament prorogued the Carneyites have been ladling out billions of dollars both pre-and post-election to keep the economy from stagnating. Still, 1.4 million Canadians missed credit payments in the first three months of 2025, up 146K from this time last year.

Getting as far away from this economic collapse as possible might just be the biggest incentive for Albertans to run their own show in the future. Siphoning off energy profits to save Toronto and Ottawa from condo crates and phoney real estate developments is hardly a patriotic incentive. (To say nothing of getting away from the offshore money-laundering operations now thriving in Canada.)

Carney’s Throne speech that was supposed to woo the West was full of the usual Liberal bromides that sound good but are quickly swallowed by process and review. Then pipelines he promised in the campaign? Guess again. If he’d wanted to help Canadians he’d have adopted a tax structure like Ireland, Japan or Hong Kong that would eliminate 80 percent of CRA staff.

But he’s not dong that because the Ottawa region where those CRA people live is solid red. His election owed much to white-collar unions and media that polished his apple. The contradictions between Carney’s promises and reality will soon pile up. His Euro-based climate and social media policies will tell on a jaded public. His housing minister— who has promised to stabilize house prices— produced 170 percent jump in home prices while mayor of Vancouver.

Which will give Danielle Smith all she needs to introduce plans, if not for separation, then for a new decentralized Canada. Book it by 2027.

Bruce Dowbiggin @dowbboy is the editor of Not The Public Broadcaster A two-time winner of the Gemini Award as Canada’s top television sports broadcaster, Bruce is regular media contributor. The new book from there team of Evan & Bruce Dowbiggin is Deal With It: The Trades That Stunned The NHL & Changed Hockey. From Espo to Boston in 1967 to Gretz in L.A. in 1988 to Patrick Roy leaving Montreal in 1995, the stories behind the story. In paperback and Kindle on #Amazon. Destined to be a hockey best seller. https://www.amazon.ca/Deal-Trades-Stunned-Changed-Hockey-ebook/dp/B0D236NB35/

-

Business15 hours ago

Business15 hours agoRFK Jr. says Hep B vaccine is linked to 1,135% higher autism rate

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta Independence Seekers Take First Step: Citizen Initiative Application Approved, Notice of Initiative Petition Issued

-

Crime1 day ago

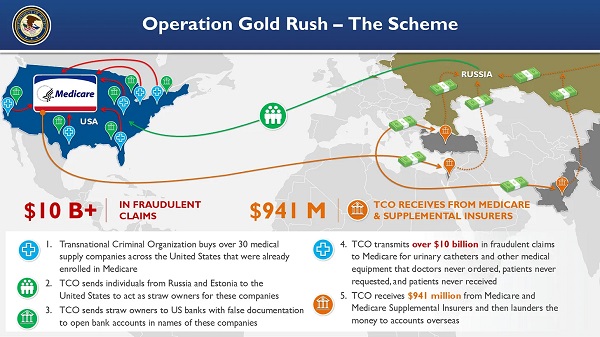

Crime1 day agoNational Health Care Fraud Takedown Results in 324 Defendants Charged in Connection with Over $14.6 Billion in Alleged Fraud

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoSuspected ambush leaves two firefighters dead in Idaho

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoWhy the West’s separatists could be just as big a threat as Quebec’s

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCanada Caves: Carney ditches digital services tax after criticism from Trump

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoRFK Jr. Unloads Disturbing Vaccine Secrets on Tucker—And Surprises Everyone on Trump

-

Censorship Industrial Complex16 hours ago

Censorship Industrial Complex16 hours agoGlobal media alliance colluded with foreign nations to crush free speech in America: House report