Brownstone Institute

Pfizer Lied to Us Again

From Brownstone Institute

BY

There used to be a time where claims from pharmaceutical companies may have been treated with some degree of skepticism from major institutions and media outlets.

Yet in late 2020 and into 2021, suddenly skepticism turned to complete blind faith. But what changed? Why, political incentives, of course!

Initially, Covid vaccines produced by Pfizer were seen as dangerous and untested; they were considered a Trump vaccine that only idiots who were willing to risk their own health would take. However when the 2020 election had been officially decided, and Biden and his political allies represented the Covid vaccines as the pathway out of the pandemic, a moral choice that would help yourself and others, narratives and incentives changed dramatically.

Pfizer became a heroic symbol of virtue, and all questioning of Covid vaccines was grounds for immediate expulsion from polite society, regardless of the actual efficacy of Pfizer’s products.

Much of the blame for the vaccines’ underperformance could be placed on Pfizer itself; the company relentlessly promoted hopelessly inaccurate efficacy estimates and supported efforts to unnecessarily mandate mRNA shots.

Sure enough, on the back of progressive orthodoxy, corporate and institutional incompetence and media activism, they proudly reported record revenues.

We all know how that turned out in 2022 and 2023.

Skepticism towards Pfizer’s vaccine was obviously quite well warranted. And it turns out that now we, and of course, Pfizer’s chief promoters in the media and public health class should have been even more skeptical.

They weren’t.

Pfizer’s Claims On Covid Treatments Were Wildly Inaccurate

As the Covid vaccines failed spectacularly to stop the spread of infections and did nothing to lessen all-cause mortality or even decrease population level Covid-associated deaths in highly vaccinated countries, Pfizer saw another opportunity.

Sure, their signature product failed to perform as expected. So why not create another one as an antidote?

Enter Paxlovid.

Paxlovid, an antiviral drug, was supposed to help individuals with symptomatic Covid, who’d already been infected, recover more quickly and lessen the risk of severe illness. Sounds great right?

It would appear that it sure did to Anthony Fauci and the cadre of media-promoted “experts.”

Fauci praised Paxlovid in 2022, after the mRNA vaccines and booster doses failed to prevent him from contracting Covid. Bizarrely, Fauci implied that the same Pfizer products that he demanded everyone take would not have been enough to keep him healthy, saying that he believed Paxlovid had kept him out of the hospital.

Never mind, of course, that Fauci had a “rebound” case of Covid-19 after taking Paxlovid and getting vaccinated and boosted. Acknowledging imperfections would undercut his desire to get everyone to take more of his preferred products.

Paxlovid made headlines again later in 2022 as Rochelle Walensky also praised Pfizer’s efforts, despite once again testing positive for “rebound” Covid after Paxlovid treatments.

Even today, the CDC’s own website says Paxlovid is an “effective” treatment for those who’ve contracted the virus and want to avoid severe illness.

There’s just one problem; it’s not true.

A newly released study on Paxlovid on randomized adults with symptomatic Covid; one subset was given Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir-ritonavir) or a placebo every 12 hours for five days, with the intent of determining how effective it was at “sustained alleviation” of Covid-19 symptoms.

In this phase 2–3 trial, we randomly assigned adults who had confirmed Covid-19 with symptom onset within the past 5 days in a 1:1 ratio to receive nirmatrelvir–ritonavir or placebo every 12 hours for 5 days. Patients who were fully vaccinated against Covid-19 and who had at least one risk factor for severe disease, as well as patients without such risk factors who had never been vaccinated against Covid-19 or had not been vaccinated within the previous year, were eligible for participation. Participants logged the presence and severity of prespecified Covid-19 signs and symptoms daily from day 1 through day 28. The primary end point was the time to sustained alleviation of all targeted Covid-19 signs and symptoms. Covid-19–related hospitalization and death from any cause were also assessed through day 28.

Spoiler alert: it wasn’t effective at all.

Their measured results revealed that there was effectively no difference whatsoever in the “sustained alleviation” of symptoms between Paxlovid and a placebo. Those taking Pfizer’s miracle antiviral treatment saw their “signs and symptoms” resolve after 12 days, while the placebo recipients took 13 days.

The median time to sustained alleviation of all targeted signs and symptoms of Covid-19 was 12 days in the nirmatrelvir–ritonavir group and 13 days in the placebo group (P=0.60). Five participants (0.8%) in the nirmatrelvir–ritonavir group and 10 (1.6%) in the placebo group were hospitalized for Covid-19 or died from any cause (difference, −0.8 percentage points; 95% confidence interval, −2.0 to 0.4).

This is the product that to this day is relentlessly promoted by the CDC, the media, and politicians as an effective tool to reduce the severity of symptoms and the length of illness. And it was virtually meaningless.

Even with regards to the most severe outcomes, hospitalization, and death, the difference was negligible. Confidence intervals for the difference in outcome even stretched to a positive relationship, meaning that it’s within the bounds of possibility that more people died or were hospitalized after taking Paxlovid than a placebo.

Succinctly, the researchers confirmed in their summary that there was no difference between the two treatments.

The time to sustained alleviation of all signs and symptoms of Covid-19 did not differ significantly between participants who received nirmatrelvir–ritonavir and those who received placebo.

But who are these researchers, you might ask…surely they’re fringe scientists, desperate to undercut a big, bad pharmaceutical company, right? How else could their conclusions so thoroughly undermine Pfizer?

Let’s take a look at the disclosure to see who funded this study, designed the trial, conducted it, collected the data, and analyzed the results. Surely, that will reveal the nefarious intentions behind this dastardly attempt to cut at the heart of Pfizer’s miracle drug.

Pfizer was responsible for the trial design and conduct and for data collection, analysis, and interpretation. The first draft of the manuscript was written by medical writers (funded by Pfizer) under direction from the authors.

Oh. Oh no.

Pfizer created the trial, conducted it, collected the data, and analyzed it. And it found that Paxlovid made no difference to the resolution of symptoms or with keeping people alive or out of the hospital. That has to sting.

Even worse, Covid vaccination was once again proven to be almost entirely irrelevant where results were concerned. Results were the same between “high-risk subgroups,” meaning those who had been vaccinated but had an elevated risk for more serious symptoms, and those who had never been vaccinated or had received the last dose more than a year ago.

Similar results were observed in the high-risk subgroup (i.e., participants who had been vaccinated and had at least one risk factor for severe illness) and in the standard-risk subgroup (i.e., those who had no risk factors for severe illness and had never been vaccinated or had not been vaccinated within the previous 12 months).

So not only did Paxlovid not make a difference, but vaccination status AND Paxlovid wasn’t enough to create a sizable gap in outcomes between healthy, unvaccinated individuals.

But wait, there’s more.

Viral load rebounds were also more common in the Paxlovid group, and symptom and viral load rebounds combined were more common among those taking Pfizer’s treatment. While percentages were generally low, other studies have pegged Paxlovid-associated rebound as occurring nearly one quarter of the time.

So it’s not particularly effective at reducing symptoms or resolving them more quickly, doesn’t lead to statistically significant improvements in the most severe outcomes, and is more likely to result in a rebound case of the illness it’s supposed to be protecting you from.

Sounds exactly like the type of product that Fauci, Walensky, and the CDC would praise, doesn’t it?

Paxlovid is the entire Covid-pharmaceutical complex summarized perfectly. Created to solve a problem that was supposed to be fixed by another product…understudied, overhyped by the “experts,” and prematurely authorized by a desperate FDA…and ultimately shown to be mostly ineffective.

Once again, the actual science disproves The Science™. And once again, we’ll get no acknowledgment of it or apologies for the billions of taxpayer dollars wasted. Can’t wait to see what Pfizer does for an encore.

Republished from the author’s Substack

Brownstone Institute

Bizarre Decisions about Nicotine Pouches Lead to the Wrong Products on Shelves

From the Brownstone Institute

A walk through a dozen convenience stores in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, says a lot about how US nicotine policy actually works. Only about one in eight nicotine-pouch products for sale is legal. The rest are unauthorized—but they’re not all the same. Some are brightly branded, with uncertain ingredients, not approved by any Western regulator, and clearly aimed at impulse buyers. Others—like Sweden’s NOAT—are the opposite: muted, well-made, adult-oriented, and already approved for sale in Europe.

Yet in the United States, NOAT has been told to stop selling. In September 2025, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued the company a warning letter for offering nicotine pouches without marketing authorization. That might make sense if the products were dangerous, but they appear to be among the safest on the market: mild flavors, low nicotine levels, and recyclable paper packaging. In Europe, regulators consider them acceptable. In America, they’re banned. The decision looks, at best, strange—and possibly arbitrary.

What the Market Shows

My October 2025 audit was straightforward. I visited twelve stores and recorded every distinct pouch product visible for sale at the counter. If the item matched one of the twenty ZYN products that the FDA authorized in January, it was counted as legal. Everything else was counted as illegal.

Two of the stores told me they had recently received FDA letters and had already removed most illegal stock. The other ten stores were still dominated by unauthorized products—more than 93 percent of what was on display. Across all twelve locations, about 12 percent of products were legal ZYN, and about 88 percent were not.

The illegal share wasn’t uniform. Many of the unauthorized products were clearly high-nicotine imports with flashy names like Loop, Velo, and Zimo. These products may be fine, but some are probably high in contaminants, and a few often with very high nicotine levels. Others were subdued, plainly meant for adult users. NOAT was a good example of that second group: simple packaging, oat-based filler, restrained flavoring, and branding that makes no effort to look “cool.” It’s the kind of product any regulator serious about harm reduction would welcome.

Enforcement Works

To the FDA’s credit, enforcement does make a difference. The two stores that received official letters quickly pulled their illegal stock. That mirrors the agency’s broader efforts this year: new import alerts to detain unauthorized tobacco products at the border (see also Import Alert 98-06), and hundreds of warning letters to retailers, importers, and distributors.

But effective enforcement can’t solve a supply problem. The list of legal nicotine-pouch products is still extremely short—only a narrow range of ZYN items. Adults who want more variety, or stores that want to meet that demand, inevitably turn to gray-market suppliers. The more limited the legal catalog, the more the illegal market thrives.

Why the NOAT Decision Appears Bizarre

The FDA’s own actions make the situation hard to explain. In January 2025, it authorized twenty ZYN products after finding that they contained far fewer harmful chemicals than cigarettes and could help adult smokers switch. That was progress. But nine months later, the FDA has approved nothing else—while sending a warning letter to NOAT, arguably the least youth-oriented pouch line in the world.

The outcome is bad for legal sellers and public health. ZYN is legal; a handful of clearly risky, high-nicotine imports continue to circulate; and a mild, adult-market brand that meets European safety and labeling rules is banned. Officially, NOAT’s problem is procedural—it lacks a marketing order. But in practical terms, the FDA is punishing the very design choices it claims to value: simplicity, low appeal to minors, and clean ingredients.

This approach also ignores the differences in actual risk. Studies consistently show that nicotine pouches have far fewer toxins than cigarettes and far less variability than many vapes. The biggest pouch concerns are uneven nicotine levels and occasional traces of tobacco-specific nitrosamines, depending on manufacturing quality. The serious contamination issues—heavy metals and inconsistent dosage—belong mostly to disposable vapes, particularly the flood of unregulated imports from China. Treating all “unauthorized” products as equally bad blurs those distinctions and undermines proportional enforcement.

A Better Balance: Enforce Upstream, Widen the Legal Path

My small Montgomery County survey suggests a simple formula for improvement.

First, keep enforcement targeted and focused on suppliers, not just clerks. Warning letters clearly change behavior at the store level, but the biggest impact will come from auditing distributors and importers, and stopping bad shipments before they reach retail shelves.

Second, make compliance easy. A single-page list of authorized nicotine-pouch products—currently the twenty approved ZYN items—should be posted in every store and attached to distributor invoices. Point-of-sale systems can block barcodes for anything not on the list, and retailers could affirm, once a year, that they stock only approved items.

Third, widen the legal lane. The FDA launched a pilot program in September 2025 to speed review of new pouch applications. That program should spell out exactly what evidence is needed—chemical data, toxicology, nicotine release rates, and behavioral studies—and make timely decisions. If products like NOAT meet those standards, they should be authorized quickly. Legal competition among adult-oriented brands will crowd out the sketchy imports far faster than enforcement alone.

The Bottom Line

Enforcement matters, and the data show it works—where it happens. But the legal market is too narrow to protect consumers or encourage innovation. The current regime leaves a few ZYN products as lonely legal islands in a sea of gray-market pouches that range from sensible to reckless.

The FDA’s treatment of NOAT stands out as a case study in inconsistency: a quiet, adult-focused brand approved in Europe yet effectively banned in the US, while flashier and riskier options continue to slip through. That’s not a public-health victory; it’s a missed opportunity.

If the goal is to help adult smokers move to lower-risk products while keeping youth use low, the path forward is clear: enforce smartly, make compliance easy, and give good products a fair shot. Right now, we’re doing the first part well—but failing at the second and third. It’s time to fix that.

Addictions

The War on Commonsense Nicotine Regulation

From the Brownstone Institute

Cigarettes kill nearly half a million Americans each year. Everyone knows it, including the Food and Drug Administration. Yet while the most lethal nicotine product remains on sale in every gas station, the FDA continues to block or delay far safer alternatives.

Nicotine pouches—small, smokeless packets tucked under the lip—deliver nicotine without burning tobacco. They eliminate the tar, carbon monoxide, and carcinogens that make cigarettes so deadly. The logic of harm reduction couldn’t be clearer: if smokers can get nicotine without smoke, millions of lives could be saved.

Sweden has already proven the point. Through widespread use of snus and nicotine pouches, the country has cut daily smoking to about 5 percent, the lowest rate in Europe. Lung-cancer deaths are less than half the continental average. This “Swedish Experience” shows that when adults are given safer options, they switch voluntarily—no prohibition required.

In the United States, however, the FDA’s tobacco division has turned this logic on its head. Since Congress gave it sweeping authority in 2009, the agency has demanded that every new product undergo a Premarket Tobacco Product Application, or PMTA, proving it is “appropriate for the protection of public health.” That sounds reasonable until you see how the process works.

Manufacturers must spend millions on speculative modeling about how their products might affect every segment of society—smokers, nonsmokers, youth, and future generations—before they can even reach the market. Unsurprisingly, almost all PMTAs have been denied or shelved. Reduced-risk products sit in limbo while Marlboros and Newports remain untouched.

Only this January did the agency relent slightly, authorizing 20 ZYN nicotine-pouch products made by Swedish Match, now owned by Philip Morris. The FDA admitted the obvious: “The data show that these specific products are appropriate for the protection of public health.” The toxic-chemical levels were far lower than in cigarettes, and adult smokers were more likely to switch than teens were to start.

The decision should have been a turning point. Instead, it exposed the double standard. Other pouch makers—especially smaller firms from Sweden and the US, such as NOAT—remain locked out of the legal market even when their products meet the same technical standards.

The FDA’s inaction has created a black market dominated by unregulated imports, many from China. According to my own research, roughly 85 percent of pouches now sold in convenience stores are technically illegal.

The agency claims that this heavy-handed approach protects kids. But youth pouch use in the US remains very low—about 1.5 percent of high-school students according to the latest National Youth Tobacco Survey—while nearly 30 million American adults still smoke. Denying safer products to millions of addicted adults because a tiny fraction of teens might experiment is the opposite of public-health logic.

There’s a better path. The FDA should base its decisions on science, not fear. If a product dramatically reduces exposure to harmful chemicals, meets strict packaging and marketing standards, and enforces Tobacco 21 age verification, it should be allowed on the market. Population-level effects can be monitored afterward through real-world data on switching and youth use. That’s how drug and vaccine regulation already works.

Sweden’s evidence shows the results of a pragmatic approach: a near-smoke-free society achieved through consumer choice, not coercion. The FDA’s own approval of ZYN proves that such products can meet its legal standard for protecting public health. The next step is consistency—apply the same rules to everyone.

Combustion, not nicotine, is the killer. Until the FDA acts on that simple truth, it will keep protecting the cigarette industry it was supposed to regulate.

-

COVID-1923 hours ago

COVID-1923 hours agoCrown seeks to punish peaceful protestor Chris Barber by confiscating his family work truck “Big Red”

-

MAiD1 day ago

MAiD1 day agoHealth Canada suggests MAiD expansion by pre-approving ‘advance requests’

-

Alberta24 hours ago

Alberta24 hours agoPremier Danielle Smith says attacks on Alberta’s pro-family laws ‘show we’ve succeeded in a lot of ways’

-

Agriculture10 hours ago

Agriculture10 hours agoHealth Canada indefinitely pauses plan to sell unlabeled cloned meat after massive public backlash

-

Indigenous24 hours ago

Indigenous24 hours agoCanadian mayor promises to ‘vigorously defend’ property owners against aboriginal land grab

-

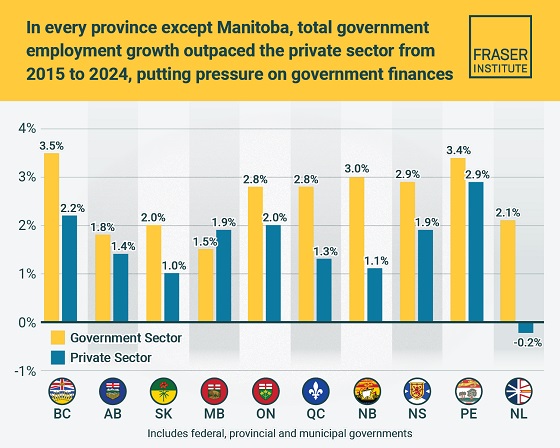

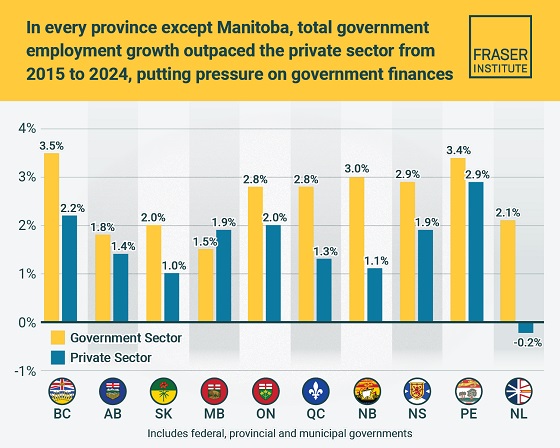

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoTaxpayers paying wages and benefits for 30% of all jobs created over the last 10 years

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoOrgan donation industry’s redefinitions of death threaten living people

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoEXCLUSIVE: Here’s An Inside Look At The UN’s Disastrous Climate Conference