Business

New Towns Offer a Solution to Canada’s Housing Crisis

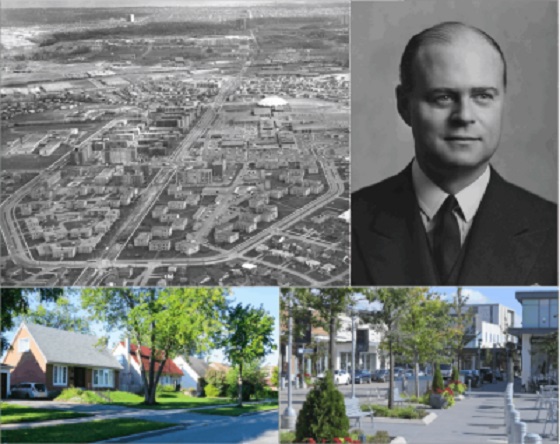

The postwar Canadian Dream: Don Mills, unveiled in 1953, was Canada’s first self-contained, suburban New Town. The brainchild of industrialist E.P. Taylor (top right), it offered young Canadian families the opportunity to abandon hectic downtown living for a more bucolic lifestyle in the suburbs.

By John Roe

Prime Minister Mark Carney says his plan to end Canada’s interminable housing crisis is to “Build Baby Build”. We can hope.

Unfortunately, Carney’s current plan is little more than a collection of unproven proposals and old policy mistakes including modular homes, boutique tax breaks, billions of taxpayer dollars in loans or subsidies and a new federal building authority.

The enormity of the task demands much broader thinking. Rather than simply encouraging a stacked townhouse here, and a condo there, Canada needs to remember what has worked in the past. And what other countries are doing today. With this in mind, Carney should embrace New Towns.

Also known as Garden Cities or Satellite Cities, New Towns are brand-new, planned communities of 10,000 or more citizens and that stand apart from existing urban centres. These are more than the suburbs reflexively loathed by so many planners and environmentalists. Rather, New Towns can offer a diverse mixture of living options, ranging from ground-level housing to built-to-purpose rental apartments and condominiums. As self-contained communities, they include schools, community centres along with shopping and employment opportunities.

New Towns represent the marriage of inspired utopianism with pragmatic realism. And they can provide the home so many of us crave.

Originally conceived in Britain during the Industrial Age, Canada witnessed its own New Town building boom during the post-war era. Communities built in the 1950s and 1960s including Don Mills, Bramalea, and Erin Mills in Ontario were all designed as separate entities meant to relieve population pressure on nearby Toronto. Other New Towns took advantage of new resource opportunities. Examples here including Thompson, Manitoba which sprang up around a nickel mine, and Kitimat, B.C., which was built to house workers in the aluminum industry.

While New Town development largely died off in the 1970s and 1980s, it is enjoying a revival today in many other countries.

Facing his own housing crisis and building on his country’s past experience, British Labour Prime Minister Keir Starmer has established a New Towns Taskforce that will soon choose 12 sites where construction on new communities will begin by 2029.

On the other side of the Atlantic — and the political spectrum — U.S. President Donald Trump — has proposed awarding 10 new city charters for building New Towns on underdeveloped federal land.

Meanwhile, several Silicon Valley billionaires are backing Solano, a planned city 60 miles east of San Francisco with a goal of creating a new community of up to 400,000 people by 2040. And Elon Musk is already building a New Town at Starbase, Texas as the headquarters for his SpaceX rocket firm.

To be fair, not every New Town has been a success. In the late 1960s, Ontario tried to build a brand-new city on the shores of Lake Erie known as Townsend. Planned as a home for up to 100,000 people, the project fizzled for a variety of reasons, including a lack of proper transportation links and other important infrastructure, such as schools or a hospital. Today, fewer than 1,000 people live there.

Despite the lessons of the past, there are three compelling reasons why Carney should include New Towns as part of his solution to Canada’s housing crisis.

First, by starting with a blank canvas, a New Town offers the chance to avoid the stultifying NIMBYism of existing home owners and municipal officials who often stand in the way of new development. The status quo is one of the biggest obstacles to ending the housing crisis, and New Towns are by their very nature new.

Second, because New Towns are located outside existing urban centres, they offer the promise of delivering ground-level homes with a yard and driveway that so many young Canadians say they want. Focusing growth exclusively in existing urban centres such as Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal – as Carney seems to be doing – will deliver greater density, but not fulfil the housing dreams of Canadian families.

Third, New Towns can herald a more prosperous and unified Canada for the 21 st century. New Towns could be built in regions such as Ontario’s Ring of Fire, rich with minerals the world demands. New Towns could also tighten the east-west ties that bind the country together. Further, this growth can be focused on areas with marginal farmland, such as the Canadian Shield, which in Ontario starts just a 90 minute drive north of

Toronto.

New Towns are already beginning to pop up in Canada. In 2017, for example, construction began on Seaton Community, a satellite town adjacent to Pickering Ontario that will eventually grow into six neighbourhoods with up to 70,000 residents. And this spring, the southwestern Ontario municipality of Central Elgin unveiled plans for a New Town of 9,000 residents on the edge of St. Thomas.

Having promised Canadians fast and decisive “elbows up” leadership, our prime minister should throw his weight behind New Towns. To begin, he could appoint a New Town Task Force, similar to the one in Britain to get to work identifying potential locations. Even better, he could simply say his government thinks New Towns are a good idea and let the private sector do all the heavy lifting.

If the millions of Canadians currently shut out of the housing market are to have any chance at owning the home of their dreams, New Towns need to be in the mix.

John Roe is a Kitchener, Ont. freelance writer and former editorial page editor of the Waterloo Region Record. The original and longer version of this story first appeared at C2CJournal.ca

Business

Canada has given $109 million to Communist China for ‘sustainable development’ since 2015

From LifeSiteNews

A briefing note showed Canadian aid has gone to ‘key foreign policy priorities in China, including human rights, gender equality, sustainable development, and climate change.’

A federal briefing note disclosed that well over $100 million has been provided to the Communist Chinese government in so-called “foreign aid” to promote “sustainable development” that includes woke ideology such as gender equality.

As reported by Blacklock’s Reporter, a recent briefing note titled Assistance to China from May for the Minister of International Development showed $109 million has gone to “key foreign policy priorities in China, including human rights, gender equality, sustainable development, and climate change” since 2015 and $645 million since 2003.

The briefing note asked directly if funding was “going to the Government of China.”

In reply, the briefing note stated, “Canada has not provided direct bilateral assistance to Chinese state authorities since 2013, though it continues to provide small amounts of funding to international partners and non-state partners on the ground.”

Former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau came to power in 2015 and increased relations with the Communist Chinese regime. This trend under the Liberal Party government has continued with Prime Minister Mark Carney.

During a 2025 federal election campaign debate, Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre called out Carney for his ties to Communist China.

Conservative MP Andrew Scheer has consistently called out any money at all going to China, saying, “I don’t believe Canadian taxpayers should be sending any money to China.”

“We’re talking about a Communist dictatorial government that abuses human rights, quashes freedoms, violates rights of its citizens, and has a very aggressive foreign policy throughout the region,” he noted.

Scheer added that he has been calling on the Carney Liberals to “stand up for themselves, stand up for Canadians, stop being bullied and pushed around on the world stage, especially by China.”

Most of the money in foreign aid was spent through globalist-backed agencies such as the World Bank and the United Nations Development Program. Some 39 percent of the money was said to have gone straight to Chinese recipients, but no projects were itemized.

Other countries have received millions of dollars in foreign aid, with $2.1 billion going to Ukraine, $195 million to Ethiopia, $172 million to Haiti, and $151 million to the West Bank and Gaza last year.

Foreign aid to all nations totaled $12.3 billion.

LifeSiteNews recently reported that the Canadian Liberal government gave millions in aid to Chinese universities.

China has been accused of direct election meddling in Canada, as reported by LifeSiteNews.

LifeSiteNews also reported that a new exposé by investigative journalist Sam Cooper has claimed there is compelling evidence that Carney and Trudeau are/were strongly influenced by an “elite network” of foreign actors, including those with ties to China and the World Economic Forum.

Business

Canada’s combative trade tactics are backfiring

This article supplied by Troy Media.

Defiant messaging may play well at home, but abroad it fuels mistrust, higher tariffs and a steady erosion of Canada’s agri-food exports

The real threat to Canadian exporters isn’t U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariffs, it’s Ottawa and Queen’s Park’s reckless diplomacy.

The latest tariff hike, whether triggered by Ontario’s anti-tariff ad campaign or not, is only a symptom. The deeper problem is Canada’s escalating loss of credibility at the trade table. Washington’s move to raise duties from 35 per cent to 45 per cent on nonCUSMA imports (goods not covered under the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement, the successor to NAFTA) reflects a diplomatic climate that is quickly souring, with very real consequences for Canadian exporters.

Some analysts argue that a 10-point tariff increase is inconsequential. It is not. The issue isn’t just what is being tariffed; it is the tone of the relationship. Canada is increasingly seen as erratic and reactive, negotiating from emotion rather than strategy. That kind of reputation is dangerous when dealing with the U.S., which remains Canada’s most important trade partner by a wide margin.

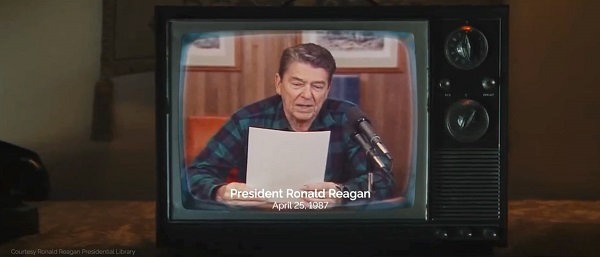

Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s stand up to America messaging, complete with a nostalgic Ronald Reagan cameo, may have been rooted in genuine conviction. Many Canadians share his instinct to defend the country’s interests with bold language. But in diplomacy, tone often outweighs intent. What plays well domestically can sound defiant abroad, and the consequences are already being felt in boardrooms and warehouses across the country.

Ford’s public criticisms of companies such as Crown Royal, accused of abandoning Ontario, and Stellantis, which recently announced it will shift production of its Jeep Compass from Brampton to Illinois as part of a US$13 billion U.S. investment, may appeal to voters who like to see politicians get tough. But those theatrics reinforce the impression that Canada is hostile to

international investors. At a time when global capital can move freely, that perception is damaging. Collaboration, not confrontation, is what’s needed most to secure investment in Canada’s economy.

Such rhetoric fuels uncertainty on both sides of the border. The results are clear: higher tariffs, weaker investor confidence and American partners quietly pivoting away from Canadian suppliers.

Many Canadian food exporters are already losing U.S. accounts, not because of trade rules but because of eroding trust. Executives in the agri-food sector are beginning to wonder whether Canada can still be counted on as a reliable partner, and some have already shifted contracts southward.

Ford’s political campaigns may win applause locally, but Washington’s retaliatory measures do not distinguish between provinces. They hit all exporters, including Canada’s food manufacturers that rely heavily on the U.S. market, which purchases more than half of Canada’s agri-food exports. That means farmers, processors and transportation companies across the country are caught in the crossfire.

Those who believe the new 45 per cent rate will have little effect are mistaken. Some Canadian importers now face steeper duties than competitors in Vietnam, Laos or even Myanmar. And while tariffs matter, perception matters more. Right now, the optics for Canada’s agri-food sector are poor, and once confidence is lost, it is difficult to regain.

While many Canadians dismiss Trump as unpredictable, the deeper question is what happened to Canada’s once-cohesive Team Canada approach to trade. The agri-food industry depends on stability and predictability. Alienating our largest customer, representing 34 per cent of the global consumer market and millions of Canadian jobs tied to trade, is not just short-sighted, it’s economically reckless.

There is no trade war. What we are witnessing is an American recalibration of domestic fiscal policy with global consequences. Canada must adapt with prudence, not posturing.

The lesson is simple: reckless rhetoric is costing Canada far more than tariffs. It’s time to change course, especially at Queen’s Park.

Dr. Sylvain Charlebois is a Canadian professor and researcher in food distribution and policy. He is senior director of the Agri-Food Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University and co-host of The Food Professor Podcast. He is frequently cited in the media for his insights on food prices, agricultural trends, and the global food supply chain

Troy Media empowers Canadian community news outlets by providing independent, insightful analysis and commentary. Our mission is to support local media in helping Canadians stay informed and engaged by delivering reliable content that strengthens community connections and deepens understanding across the country

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoPremier Smith sending teachers back to school and setting up classroom complexity task force

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe painful return of food inflation exposes Canada’s trade failures

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoCoutts border officers seize 77 KG of cocaine in commercial truck entering Canada – Street value of $7 Million

-

International17 hours ago

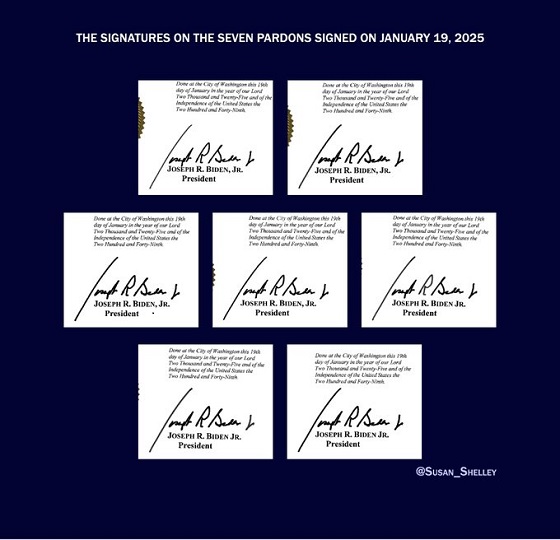

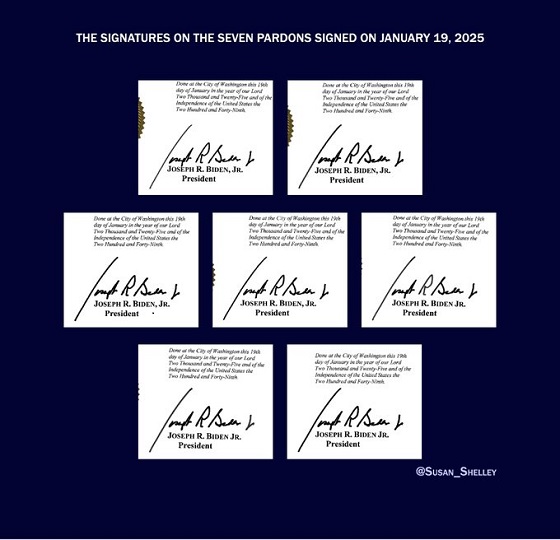

International17 hours agoBiden’s Autopen Orders declared “null and void”

-

Business20 hours ago

Business20 hours agoTrans Mountain executive says it’s time to fix the system, expand access, and think like a nation builder

-

National2 days ago

National2 days agoElection Officials Warn MPs: Canada’s Ballot System Is Being Exploited

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoOttawa Bought Jobs That Disappeared: Paying for Trudeau’s EV Gamble

-

Canada Free Press18 hours ago

Canada Free Press18 hours agoThe real genocide is not taking place in Gaza, but in Nigeria