Addictions

New lawsuit challenges Ontario’s decision to prohibit safe consumption services

Kensington Market Overdose Prevention Site in Toronto, Dec. 18, 2024. [Photo credit: Alexandra Keeler]

Critics says Ontario’s plan to replace supervised consumption sites with HART Hubs will exacerbate harms to drug addicts and strain the health-care system

The operator of a Toronto overdose prevention site is challenging Ontario’s decision to prohibit 10 supervised consumption sites from offering their services.

In December, Neighbourhood Group Community Services and two individuals launched a constitutional challenge to Ontario legislation that imposes 200-metre buffer zones between supervised consumption sites and schools and daycares. The Neighbourhood Group will be forced to close its site in Toronto’s Kensington Market as a result.

In its court challenge, the organization is arguing site closures discriminate against individuals with “substance use disabilities” and increase drug users’ risk of death and disease.

The challenge is the latest sign of growing opposition to Ontario’s decision to either shutter supervised consumption sites or transition them into Homelessness and Addiction Recovery Treatment (HART) Hubs. The hubs will offer drug users a range of primary care and housing solutions, but not supervised consumption, needle exchanges or the “safe supply” of prescription drugs.

Critics say the decision to suspend supervised consumption services will harm drug users and the health-care system.

“We’re very happy that the HART Hubs are being funded,” said Bill Sinclair, CEO of Neighbourhood Group Community Services. “They’re a great asset to the community.”

“[But] we want HART Hubs and we want supervised consumption sites.”

Our content is always free.

Subscribe to get BTN’s latest news and analysis, or donate to our journalism fund.

‘Come under fire’

On Thursday, the Ontario government announced that nine of the 10 supervised consumption sites located near centres with children would transition into HART Hubs. The Neighbourhood Group’s site is the only one not offered the opportunity to transition, because it is not provincially funded.

Laila Bellony, a harm reduction manager at a supervised consumption site at the Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre in Toronto, says she is worried that drug users may avoid using HART Hubs altogether if they do not facilitate the use of drugs under the supervision of trained staff.

Data show this oversight can prevent deaths by facilitating immediate intervention in the event of an overdose.

Bellony is also concerned the site closures will increase the strain on other health-care services. She predicts longer wait times and bed shortages in hospital emergency rooms, as well as increased paramedic response times.

“I think the next thing that will happen is the medical or health-care system is going to come under fire for being sub-par. But it’s really all starting here from this decision,” she said.

She questions how the HART Hubs will meet demand for detox and recovery services or housing solutions.

Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre and its sister site, the Queen West Site, serve hundreds of clients, Bellony says. By contrast, Ontario’s HART Hub rollout plan indicates all 19 hubs will together provide 375 new housing units across the province.

“The HART Hub model is not a horrible model,” said Bellony. “It’s the way that it’s being implemented that’s ill-informed.”

In a response to requests for comment, a media spokesperson for the Ontario Ministry of Health directed Canadian Affairs to its August news release. That release lists proposals for increased safety measures at remaining sites, and a link to a HART Hub “client journey.”

On Dec. 3, the Auditor General of Ontario, Shelley Spence, released a report criticizing the health ministry’s “outdated” opioid strategy, noting it has not been updated since 2016.

National data show a 6.7 per cent drop in opioid deaths in early 2024. But experts caution it is too soon to call it a lasting trend. Opioid toxicity deaths in 2023 were up 205 per cent from 2016.

“We concluded that the Ministry does not have effective processes in place to meet the challenging and changing nature of the opioid crisis in Ontario,” the auditor general’s report says.

“The Ministry did not … provide a thorough, evidence-based business case analysis for the 2024 new model … [HART Hubs] to ensure that they are responsive to the needs of Ontarians.”

|

Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre’s Queen West Site in Toronto, Dec. 18, 2024. [Photo credit: Alexandra Keeler]

‘Ill-informed’

Ontario has cited crime and public safety concerns as reasons for blocking supervised consumption sites near centres with children from offering their services.

“In Toronto, reports of assault in 2023 are 113 per cent higher and robbery is 97 per cent higher in neighbourhoods near these sites compared to the rest of the city,” Ontario Health Minister Sylvia Jones’ office said in an Aug. 20 press release.

The province has also cited concerns about prescription drugs dispensed through safer supply programs being diverted to the black market.

Police chiefs and sergeants in the Ontario cities of London and Ottawa have confirmed safer supply diversion is occurring in their municipalities.

“We are seeing significant increases in the availability of the diverted Dilaudid eight-milligram tablets, which are often prescribed as part of the safe supply initiatives,” London Police Chief Thai Truong said at a Nov. 26 parliamentary committee meeting examining the effect of the opioid epidemic and strategies to address it.

But Bellony disputes the claim that neighbourhoods with supervised consumption sites experience higher crime rates.

“Some of the things that [the ministry is] saying in terms of crime being up in neighborhoods with safe consumption sites — that’s not necessarily true,” she said.

In response to requests for information about the city’s crime rates, Nadine Ramadan, a senior communications advisor for the Toronto Police Service, directed Canadian Affairs to the service’s crime rate portal.

The portal shows assaults, break-and-enters and robberies in the West Queen West neighborhood have remained relatively stable since the Queen West supervised consumption site opened in 2018.

In contrast, crime rates are higher in some nearby neighbourhoods without supervised consumption sites, such as The Junction.

“While I can’t speak to perceptions about a rise in crime specifically around supervised consumption sites, I can tell you that violent crime is increasing across the GTA,” Ramadan told Canadian Affairs. She referred questions about Jones’ statements about crime data to the health minister’s office.

Jones’ office did not respond to multiple follow-up inquiries.

Mixed feelings

In July, Canadian Affairs reported that business owners in the West Queen West neighbourhood were grappling with a surge in drug-related crime.

Rob Sysak, executive director of the West Queen West Business Improvement Association, says there are mixed feelings about their neighbourhood’s site ceasing to offer safe consumption services.

“I’m not saying [the closure] is a positive or negative decision, because we won’t know until after a while,” said Sysak, whose association works to promote business in the area.

Sysak says he has heard concerns from business owners that needles previously used by individuals at the site may now end up on the street.

Bellony supports the concept of HART Hubs offering addiction and support services. But she says she finds the province’s plan for the hubs to be unclear and unrealistic.

“It seems very much like they kind of skipped forward to the ideal situation at the end,” she said. “But all the steps that it takes to get there … are unaddressed.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

The Shaky Science Behind Harm Reduction and Pediatric Gender Medicine

By Adam Zivo

Both are shaped by radical LGBTQ activism and questionable evidence.

Over the past decade, North America embraced two disastrous public health movements: pediatric gender medicine and “harm reduction” for drug use. Though seemingly unrelated, these movements are actually ideological siblings. Both were profoundly shaped by extremist LGBTQ activism, and both have produced grievous harms by prioritizing ideology over high-quality scientific evidence.

While harm reductionists are known today for championing interventions that supposedly minimize the negative effects of drug consumption, their movement has always been connected to radical “queer” activism. This alliance began during the 1980s AIDS crisis, when some LGBTQ activists, hoping to reduce HIV infections, partnered with addicts and drug-reform advocates to run underground needle exchanges.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In the early 2000s, after the North American AIDS epidemic was brought under control, many HIV organizations maintained their relevance (and funding) by pivoting to addiction issues. Despite having no background in addiction medicine, their experience with drug users in the context of infectious diseases helped them position themselves as domain experts.

These organizations tended to conceptualize addiction as an incurable infection—akin to AIDS or Hepatitis C—and as a permanent disability. They were heavily staffed by progressives who, influenced by radical theory, saw addicts as a persecuted minority group. According to them, drug use itself was not the real problem—only society’s “moralizing” norms.

These factors drove many HIV organizations to lobby aggressively for harm reduction at the expense of recovery-oriented care. Their efforts proved highly successful in Canada, where I am based, as HIV researchers were a driving force behind the implementation of supervised consumption sites and “safer supply” (free, government-supplied recreational drugs for addicts).

From the 2010s onward, the association between harm reductionism and queer radicalism only strengthened, thanks to the popularization of “intersectional” social justice activism that emphasized overlapping forms of societal oppression. Progressive advocates demanded that “marginalized” groups, including drug addicts and the LGBTQ community, show enthusiastic solidarity with one another.

These two activist camps sometimes worked on the same issues. For example, the gay community is struggling with a silent epidemic of “chemsex” (a dangerous combination of drugs and anonymous sex), which harm reductionists and queer theorists collaboratively whitewash as a “life-affirming cultural practice” that fosters “belonging.”

For the most part, though, the alliance has been characterized by shared tones and tactics—and bad epistemology. Both groups deploy politicized, low-quality research produced by ideologically driven activist-researchers. The “evidence-base” for pediatric gender medicine, for example, consists of a large number of methodologically weak studies. These often use small, non-representative samples to justify specious claims about positive outcomes. Similarly, harm reduction researchers regularly conduct semi-structured interviews with small groups of drug users. Ignoring obvious limitations, they treat this testimony as objective evidence that pro-drug policies work or are desirable.

Gender clinicians and harm reductionists are also averse to politically inconvenient data. Gender clinicians have failed to track long-term patient outcomes for medically transitioned children. In some cases, they have shunned detransitioners and excluded them from their research. Harm reductionists have conspicuously ignored the input of former addicts, who generally oppose laissez-faire drug policies, and of non-addict community members who live near harm-reduction sites.

Both fields have inflated the benefits of their interventions while concealing grievous harms. Many vulnerable children, whose gender dysphoria otherwise might have resolved naturally, were chemically castrated and given unnecessary surgeries. In parallel, supervised consumption sites and “safer supply” entrenched addiction, normalized public drug use, flooded communities with opioids, and worsened public disorder—all without saving lives.

In both domains, some experts warned about poor research practices and unmeasured harms but were silenced by activists and ideologically captured institutions. In 2015, one of Canada’s leading sexologists, Kenneth Zucker, was fired from the gender clinic he had led for decades because he opposed automatically affirming young trans-identifying patients. Analogously, dozens of Canadian health-care professionals have told me that they feared publicly criticizing aspects of the harm-reduction movement. They thought doing so could invite activist harassment while jeopardizing their jobs and grants.

By bullying critics into silence, radical activists manufactured false consensus around their projects. The harm reductionists insist, against the evidence, that safer supply saves lives. Their idea of “evidence-based policymaking” amounts to giving addicts whatever they ask for. “The science is settled!” shout the supporters of pediatric gender medicine, though several systematic reviews proved it was not.

Both movements have faced a backlash in recent years. Jurisdictions throughout the world are, thankfully, curtailing irreversible medical procedures for gender-confused youth and shifting toward a psychotherapy-based “wait and see” approach. Drug decriminalization and safer supply are mostly dead in North America and have been increasingly disavowed by once-supportive political leaders.

Harm reductionists and queer activists are trying to salvage their broken experiments, occasionally by drawing explicit parallels between their twin movements. A 2025 paper published in the International Journal of Drug Policy, for example, asserts that “efforts to control, repress, and punish drug use and queer and trans existence are rising as right-wing extremism becomes increasingly mainstream.” As such, there is an urgent need to “cultivate shared solidarity and action . . . whether by attending protests, contacting elected officials, or vocally defending these groups in hostile spaces.”

How should critics respond? They should agree with their opponents that these two radical movements are linked—and emphasize that this is, in fact, a bad thing. Large swathes of the public understand that chemically and surgically altering vulnerable children is harmful, and that addicts shouldn’t be allowed to commandeer public spaces. Helping more people grasp why these phenomena arose concurrently could help consolidate public support for reform and facilitate a return to more restrained policies.

Adam Zivo is director of the Canadian Centre for Responsible Drug Policy.

For the full experience, please upgrade your subscription and support a public interest startup.

We break international stories and this requires elite expertise, time and legal costs.

Addictions

BC premier admits decriminalizing drugs was ‘not the right policy’

From LifeSiteNews

Premier David Eby acknowledged that British Columbia’s liberal policy on hard drugs ‘became was a permissive structure that … resulted in really unhappy consequences.’

The Premier of Canada’s most drug-permissive province admitted that allowing the decriminalization of hard drugs in British Columbia via a federal pilot program was a mistake.

Speaking at a luncheon organized by the Urban Development Institute last week in Vancouver, British Columbia, Premier David Eby said, “I was wrong … it was not the right policy.”

Eby said that allowing hard drug users not to be fined for possession was “not the right policy.

“What it became was a permissive structure that … resulted in really unhappy consequences,” he noted, as captured by Western Standard’s Jarryd Jäger.

LifeSiteNews reported that the British Columbia government decided to stop a so-called “safe supply” free drug program in light of a report revealing many of the hard drugs distributed via pharmacies were resold on the black market.

Last year, the Liberal government was forced to end a three-year drug decriminalizing experiment, the brainchild of former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government, in British Columbia that allowed people to have small amounts of cocaine and other hard drugs. However, public complaints about social disorder went through the roof during the experiment.

This is not the first time that Eby has admitted he was wrong.

Trudeau’s loose drug initiatives were deemed such a disaster in British Columbia that Eby’s government asked Trudeau to re-criminalize narcotic use in public spaces, a request that was granted.

Records show that the Liberal government has spent approximately $820 million from 2017 to 2022 on its Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy. However, even Canada’s own Department of Health in a 2023 report admitted that the Liberals’ drug program only had “minimal” results.

Official figures show that overdoses went up during the decriminalization trial, with 3,313 deaths over 15 months, compared with 2,843 in the same time frame before drugs were temporarily legalized.

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoPremier Smith sending teachers back to school and setting up classroom complexity task force

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe painful return of food inflation exposes Canada’s trade failures

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoCoutts border officers seize 77 KG of cocaine in commercial truck entering Canada – Street value of $7 Million

-

International14 hours ago

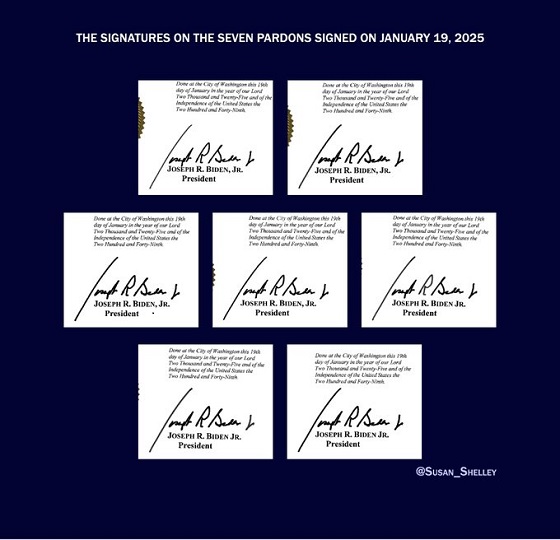

International14 hours agoBiden’s Autopen Orders declared “null and void”

-

Business17 hours ago

Business17 hours agoTrans Mountain executive says it’s time to fix the system, expand access, and think like a nation builder

-

National2 days ago

National2 days agoElection Officials Warn MPs: Canada’s Ballot System Is Being Exploited

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoOttawa Bought Jobs That Disappeared: Paying for Trudeau’s EV Gamble

-

Canada Free Press15 hours ago

Canada Free Press15 hours agoThe real genocide is not taking place in Gaza, but in Nigeria