Canadian Energy Centre

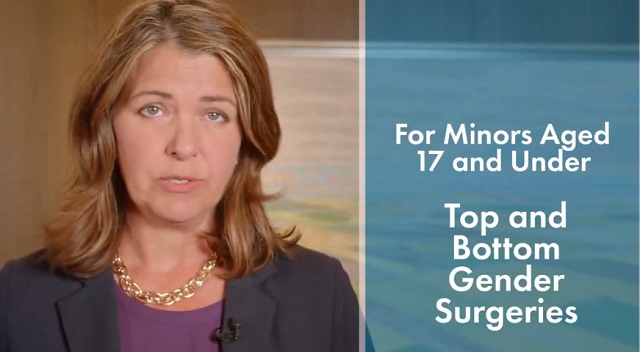

Mexico leapfrogging Canada on LNG and six other global oil and gas megaprojects

By Deborah Jaremko of the Canadian Energy Centre Ltd.

Major investments in countries like the United States, Norway, Qatar and Saudi Arabia are being made to meet world demand

New major oil and gas megaprojects around the world are proceeding amid concern about underinvestment in conventional energy leading to painful supply shortages.

“The energy future must be secure and affordable, as well as sustainable,” said Daniel Yergin, vice-chairman of S&P Global, earlier this year.

“Adequate investment that avoids shortages and price spikes, and the economic hardship and social turbulence that they bring, is essential to that future.”

Even if oil and gas demand growth slows, a cumulative $4.9 trillion will be needed between 2023 and 2030 to prevent a supply shortfall, according to a report by the International Energy Forum and S&P Global Commodity Insights.

Major investments in countries like the United States, Norway, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Mexico are being made to meet world demand.

Meanwhile, due to regulatory uncertainty and concerns over proposed policies like an emissions cap for oil and gas production, Canada’s vast resources – produced with among the world’s highest standards for environmental protection and social progress – are being left behind.

Here’s a look at just a handful of global oil and gas megaprojects, listed in rising order of development cost.

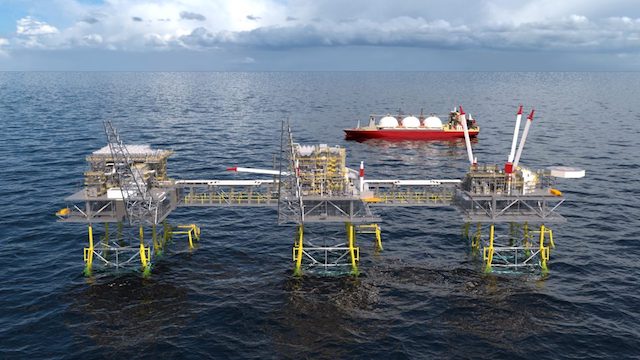

Mexico: Altamira LNG

US$1 billion

New Fortress Energy

Mexico is leapfrogging over Canada to become an LNG exporter.

While Canada’s first LNG export project is expected to start operating in 2025, Mexico’s could come online this August – less than 10 months after Mexico’s government finalized a deal with U.S.-based New Fortress Energy to make it happen.

While relatively small at 1.4 million tonnes of LNG per year (LNG Canada’s first phase will have capacity of 14 million tonnes per year), under Mexico’s agreement the Altamira site is to become an LNG hub.

New Fortress Energy is to deploy multiple same-sized floating LNG units to produce LNG from natural gas transported through TC Energy’s Sur de Texas-Tuxpan pipeline.

An existing LNG import terminal at Altamira is also expected to be converted into a 2.8-million-tonne-per-year export facility.

United States: Willow Oil Project

US$8 billion

ConocoPhillips

The U.S. government granted approval this March for the giant Willow oil project on Alaska’s North Slope to proceed.

The project, owned by ConocoPhillips, is designed to produce 180,000 barrels per day at peak and operate for 30 years. It includes a processing facility, operations centre, and three drilling sites.

The Willow leases are inside the National Petroleum Reserve – Alaska, which was established in 1923 as an emergency oil supply for the U.S. Navy. It is now administered by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

Willow would occupy about 385 acres (around half the area of Central Park in New York City) in the northeast portion of the 23-million-acre reserve. It is expected to deliver nearly US$9 billion in government revenue, creating about 2,500 jobs during construction and 300 long-term positions.

ConocoPhillips has yet to make a final investment decision, but is anticipating starting production in 2029, according to the Anchorage Daily News.

United States: Golden Pass LNG

US$10 billion

QatarEnergy, Exxon Mobil

Golden Pass LNG is one of four natural gas export terminals under construction on the U.S. Gulf Coast as the United States continues to build its platform as an LNG powerhouse.

With about 90 million tonnes per year of LNG export capacity today, analysts with Wood Mackenzie expect that if current momentum continues, another 190 million tonnes per year could come online by the end of this decade.

The US$10-billion Golden Pass project owned by QatarEnergy and Exxon Mobil will have three production trains with total export capacity of about 18 million tonnes of LNG per year.

The U.S. began exporting LNG in 2016 and has since built more LNG capacity than anywhere else in the world, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

First LNG exports from Golden Pass are planned for 2024.

Norway: Njord Field Restart

US$29 billion

Wintershall Dea, Equinor, Neptune Energy

Norway has officially reopened a major offshore oil and gas field, with the goal to extend its life beyond 2040 and double its total production.

Nearly US$30 billion in upgrades to the Njord project’s production platform and offloading vessel started in 2016, after nearly 20 years of operations. It was originally only expected to run until 2013, but improvements in recovery technology have opened the door to accessing substantially more resources.

Production restarted in December 2022, just in time to help address Europe’s energy crisis.

“With the war in Ukraine, the export of Norwegian oil and gas to Europe has never been more important than now. Reopening Njord contributes to Norway remaining a stable supplier of gas to Europe for many years to come,” Norway’s oil and energy minister Terje Aasland said in a statement.

The project will drill 10 new wells and tie in two new subsea oil and gas fields, with the work expected to add approximately 250 million barrels of oil equivalent to the European market. Partial electrification of equipment is expected to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Qatar: North Field East LNG expansion

Qatar Energy, Shell, TotalEnergies, Eni, Exxon Mobil, ConocoPhillips, Sinopec

US$29 billion

The largest LNG project ever built is underway in Qatar.

State-owned QatarEnergy’s US$29 billion North Field East Expansion will increase the country’s LNG export capacity to 110 million tonnes per year, from 77 million tonnes per year today. Startup is planned in 2025.

A planned second phase of the project will further increase capacity to 126 million tonnes per year.

World LNG demand reached a record 409 million tonnes in 2022, according to data provider Revintiv. It’s expected to rise to over 700 million tonnes by 2040, according to Shell’s most recent industry outlook.

Saudi Arabia: Jafurah Gas Project

US$110 billion

Saudi Aramco

State-owned Saudi Aramco is moving ahead with development of the massive Jafurah gas project, which it says will help meet growing energy demand and provide feedstock for hydrogen production.

First gas from the $110-billion project is expected in 2025, rising to reach two billion cubic feet per day by 2030. That’s about one-third the volume of all the natural gas produced in British Columbia. Saudi Aramco produced 10.6 billion cubic feet of natural gas per day in 2022, or more than half the gas produced in Canada.

Last year the company started construction work on the gas processing facility that is the anchor of the Jafurah project. Aramco is reportedly in talkswith potential partners to back the US$110 billion development.

Russia: Vostok Oil

US$170 billion

Rosneft

Russian state-owned oil company Rosneft continues to barrel ahead with the massive Vostok oil project in the country’s arctic, which Rosneft calls the largest investment in the world.

The US$170 billion project will use the Northern Sea Route to export about 600,000 barrels per day by 2024. Production is expected to increase to two million barrels per day after the second phase. For comparison, Canada’s entire oil sands industry produces about three million barrels per day.

The main problem the energy industry faces is global underinvestment in conventional sources, Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin said earlier this year. He stressed the importance of Vostok’s oil supply for growing Asian economies.

“Vostok Oil project will provide long-term, reliable, and guaranteed energy supplies,” Sechin said.

Two new icebreaker vessels recently helped deliver 4,600 tonnes of cargo including oil pipes for the project to the arctic development sites, the Barents Observer reported.

Canadian Energy Centre

Alberta oil sands legacy tailings down 40 per cent since 2015

Wapisiw Lookout, reclaimed site of the oil sands industry’s first tailings pond, which started in 1967. The area was restored to a solid surface in 2010 and now functions as a 220-acre watershed. Photo courtesy Suncor Energy

From the Canadian Energy Centre

By CEC Research

Mines demonstrate significant strides through technological innovation

Tailings are a byproduct of mining operations around the world.

In Alberta’s oil sands, tailings are a fluid mixture of water, sand, silt, clay and residual bitumen generated during the extraction process.

Engineered basins or “tailings ponds” store the material and help oil sands mining projects recycle water, reducing the amount withdrawn from the Athabasca River.

In 2023, 79 per cent of the water used for oil sands mining was recycled, according to the latest data from the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER).

Decades of operations, rising production and federal regulations prohibiting the release of process-affected water have contributed to a significant accumulation of oil sands fluid tailings.

The Mining Association of Canada describes that:

“Like many other industrial processes, the oil sands mining process requires water.

However, while many other types of mines in Canada like copper, nickel, gold, iron ore and diamond mines are allowed to release water (effluent) to an aquatic environment provided that it meets stringent regulatory requirements, there are no such regulations for oil sands mines.

Instead, these mines have had to retain most of the water used in their processes, and significant amounts of accumulated precipitation, since the mines began operating.”

Despite this ongoing challenge, oil sands mining operators have made significant strides in reducing fluid tailings through technological innovation.

This is demonstrated by reductions in “legacy fluid tailings” since 2015.

Legacy Fluid Tailings vs. New Fluid Tailings

As part of implementing the Tailings Management Framework introduced in March 2015, the AER released Directive 085: Fluid Tailings Management for Oil Sands Mining Projects in July 2016.

Directive 085 introduced new criteria for the measurement and closure of “legacy fluid tailings” separate from those applied to “new fluid tailings.”

Legacy fluid tailings are defined as those deposited in storage before January 1, 2015, while new fluid tailings are those deposited in storage after January 1, 2015.

The new rules specified that new fluid tailings must be ready to reclaim ten years after the end of a mine’s life, while legacy fluid tailings must be ready to reclaim by the end of a mine’s life.

Total Oil Sands Legacy Fluid Tailings

Alberta’s oil sands mining sector decreased total legacy fluid tailings by approximately 40 per cent between 2015 and 2024, according to the latest company reporting to the AER.

Total legacy fluid tailings in 2024 were approximately 623 million cubic metres, down from about one billion cubic metres in 2015.

The reductions are led by the sector’s longest-running projects: Suncor Energy’s Base Mine (opened in 1967), Syncrude’s Mildred Lake Mine (opened in 1978), and Syncrude’s Aurora North Mine (opened in 2001). All are now operated by Suncor Energy.

The Horizon Mine, operated by Canadian Natural Resources (opened in 2009) also reports a significant reduction in legacy fluid tailings.

The Muskeg River Mine (opened in 2002) and Jackpine Mine (opened in 2010) had modest changes in legacy fluid tailings over the period. Both are now operated by Canadian Natural Resources.

Imperial Oil’s Kearl Mine (opened in 2013) and Suncor Energy’s Fort Hills Mine (opened in 2018) have no reported legacy fluid tailings.

Suncor Energy Base Mine

Between 2015 and 2024, Suncor Energy’s Base Mine reduced legacy fluid tailings by approximately 98 per cent, from 293 million cubic metres to 6 million cubic metres.

Syncrude Mildred Lake Mine

Between 2015 and 2024, Syncrude’s Mildred Lake Mine reduced legacy fluid tailings by approximately 15 per cent, from 457 million cubic metres to 389 million cubic metres.

Syncrude Aurora North Mine

Between 2015 and 2024, Syncrude’s Aurora North Mine reduced legacy fluid tailings by approximately 25 per cent, from 102 million cubic metres to 77 million cubic metres.

Canadian Natural Resources Horizon Mine

Between 2015 and 2024, Canadian Natural Resources’ Horizon Mine reduced legacy fluid tailings by approximately 36 per cent, from 66 million cubic metres to 42 million cubic metres.

Total Oil Sands Fluid Tailings

Reducing legacy fluid tailings has helped slow the overall growth of fluid tailings across the oil sands sector.

Without efforts to reduce legacy fluid tailings, the total oil sands fluid tailings footprint today would be approximately 1.6 billion cubic metres.

The current fluid tailings volume stands at approximately 1.2 billion cubic metres, up from roughly 1.1 billion in 2015.

The unaltered reproduction of this content is free of charge with attribution to the Canadian Energy Centre.

Business

Why it’s time to repeal the oil tanker ban on B.C.’s north coast

The Port of Prince Rupert on the north coast of British Columbia. Photo courtesy Prince Rupert Port Authority

From the Canadian Energy Centre

By Will Gibson

Moratorium does little to improve marine safety while sending the wrong message to energy investors

In 2019, Martha Hall Findlay, then-CEO of the Canada West Foundation, penned a strongly worded op-ed in the Globe and Mail calling the federal ban of oil tankers on B.C.’s northern coast “un-Canadian.”

Six years later, her opinion hasn’t changed.

“It was bad legislation and the government should get rid of it,” said Hall Findlay, now director of the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy.

The moratorium, known as Bill C-48, banned vessels carrying more than 12,500 tonnes of oil from accessing northern B.C. ports.

Targeting products from one sector in one area does little to achieve the goal of overall improved marine transport safety, she said.

“There are risks associated with any kind of transportation with any goods, and not all of them are with oil tankers. All that singling out one part of one coast did was prevent more oil and gas from being produced that could be shipped off that coast,” she said.

Hall Findlay is a former Liberal MP who served as Suncor Energy’s chief sustainability officer before taking on her role at the University of Calgary.

She sees an opportunity to remove the tanker moratorium in light of changing attitudes about resource development across Canada and a new federal government that has publicly committed to delivering nation-building energy projects.

“There’s a greater recognition in large portions of the public across the country, not just Alberta and Saskatchewan, that Canada is too dependent on the United States as the only customer for our energy products,” she said.

“There are better alternatives to C-48, such as setting aside what are called Particularly Sensitive Sea Areas, which have been established in areas such as the Great Barrier Reef and the Galapagos Islands.”

The Business Council of British Columbia, which represents more than 200 companies, post-secondary institutions and industry associations, echoes Hall Findlay’s call for the tanker ban to be repealed.

“Comparable shipments face no such restrictions on the East Coast,” said Denise Mullen, the council’s director of environment, sustainability and Indigenous relations.

“This unfair treatment reinforces Canada’s over-reliance on the U.S. market, where Canadian oil is sold at a discount, by restricting access to Asia-Pacific markets.

“This results in billions in lost government revenues and reduced private investment at a time when our economy can least afford it.”

The ban on tanker traffic specifically in northern B.C. doesn’t make sense given Canada already has strong marine safety regulations in place, Mullen said.

Notably, completion of the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion in 2024 also doubled marine spill response capacity on Canada’s West Coast. A $170 million investment added new equipment, personnel and response bases in the Salish Sea.

“The [C-48] moratorium adds little real protection while sending a damaging message to global investors,” she said.

“This undermines the confidence needed for long-term investment in critical trade-enabling infrastructure.”

Indigenous Resource Network executive director John Desjarlais senses there’s an openness to revisiting the issue for Indigenous communities.

“Sentiment has changed and evolved in the past six years,” he said.

“There are still concerns and trust that needs to be built. But there’s also a recognition that in addition to environmental impacts, [there are] consequences of not doing it in terms of an economic impact as well as the cascading socio-economic impacts.”

The ban effectively killed the proposed $16-billion Eagle Spirit project, an Indigenous-led pipeline that would have shipped oil from northern Alberta to a tidewater export terminal at Prince Rupert, B.C.

“When you have Indigenous participants who want to advance these projects, the moratorium needs to be revisited,” Desjarlais said.

He notes that in the six years since the tanker ban went into effect, there are growing partnerships between B.C. First Nations and the energy industry, including the Haisla Nation’s Cedar LNG project and the Nisga’a Nation’s Ksi Lisims LNG project.

This has deepened the trust that projects can mitigate risks while providing economic reconciliation and benefits to communities, Dejarlais said.

“Industry has come leaps and bounds in terms of working with First Nations,” he said.

“They are treating the rights of the communities they work with appropriately in terms of project risk and returns.”

Hall Findlay is cautiously optimistic that the tanker ban will be replaced by more appropriate legislation.

“I’m hoping that we see the revival of a federal government that brings pragmatism to governing the country,” she said.

“Repealing C-48 would be a sign of that happening.”

-

Business18 hours ago

Business18 hours agoMost Canadians say retaliatory tariffs on American goods contribute to raising the price of essential goods at home

-

National1 day ago

National1 day agoWomen and girls beauty pageant urges dismissal of transgender human rights complaint

-

Alberta19 hours ago

Alberta19 hours agoCross-Canada NGL corridor will stretch from B.C. to Ontario

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoSupport for the Ukraine war continues because no one elected is actually in charge.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoTrump slaps Brazil with tariffs over social media censorship

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCBC six-figure salaries soar

-

Business19 hours ago

Business19 hours agoB.C. premier wants a private pipeline—here’s how you make that happen

-

Addictions2 days ago

Addictions2 days agoCan addiction be predicted—and prevented?