Brownstone Institute

Listen to the Kids

From the Brownstone Institute

BY

People often ask me why I still care about school closures and other covid restrictions that harmed a generation of children. “Schools are open now,” they say. “It’s enough already.”

No. It’s not. The impact to this generation of children continues. And so do many of the restrictions impacting young people.

It was just this week that New York City public schools lifted the ban on unvaccinated parents entering public school buildings.

This meant a parent who was unvaccinated could not attend a parent-teacher conference in person. Or watch their child play basketball. They could, however, attend a Knicks’ game at Madison Square Garden with 20,000 other basketball fans. This rule seemed designed specifically to punish children.

Colleges are some of the last places requiring vaccination — even boosters, in some instances, like at Fordham University. These young adults are least at risk from covid, most at risk from vaccine-induced myocarditis and are some of the last Americans required to be boosted. It makes no sense.

Rather than do my own rant about why I still care about the lasting harm done to children, I’d like to let the kids and parents speak for themselves.

The teens and parents cited below are all featured in a documentary film I’m making. I want their stories told. This all needs to be documented because the narrative is already shifting:

“Yeah schools shouldn’t have been closed so long but how could we have known! It’s over now. Time to move on.”

“Let’s declare an amnesty. We need to forgive the hard calls people needed to make without enough information. Good people did the best they could!”

“The open-schoolers may have been right but for the wrong reasons so they’re still terrible people. And besides it’s not a competition! No gloating! Let’s focus on the future!”

But it’s not over. The kids are not alright. And there is insufficient focus on how to reintegrate them and help them recover. This article, from the New York Times on January 27, lays bare the harms done, the possible lifetime effects, and the lack of attention and care being paid to helping kids recover:

I will continue to advocate for them, to tell their stories, to try to get them the help they still need and deserve. And to ensure this never happens again.

It’s time we listened to the children and parents impacted.

Garrett “Bam” Morgan, Jr., high school student. Astoria Queens, NY:

“I was so upset. Why is it that someone who pays for school and has more money to throw around . . .why do they get to play football? And I don’t. What is the difference? Because we’re playing the same sport. It’s not like they’re playing something totally drastically different. It’s the same sport. We’re doing the same things, and they get to practice, they get to play. And I don’t, and for me it was just like, why? Why me? Why my teammates? Why is it that we don’t get to have fun? Why is it that we don’t get to play the sport that we love too? How am I going to get into a college if I don’t have a junior year of football?

“I was gaining weight. And I was getting in a place where I had to start thinking of alternatives to football, thinking of life without football. Then I would try and go out and play with my friends, towards 2021 when it started to become, okay, you can somewhat go out, just stay socially distanced. But by that time, the damage was done, right?”

Scarlett Nolan, high school student. Oakland, CA:

“I didn’t make any new friends. No one did. I mean, how could you, you’re just talking to literal black boxes on a computer.”

“I don’t wanna blame it all on school closures, but it’s been a really, really big thing for me. That’s changed my life so much. That’s not how it’s supposed to go in school. You’re supposed to have school. It’s supposed to be your life. School is supposed to be your life from kindergarten to senior year. And then you go to college if you want, but that’s supposed to be your life. That’s your education. You have your friends there, you find yourself there. You find how you wanna be when you grow up there. And without that, I lost who I was completely. Everything who I was. I wasn’t that person that worked to get straight A’s anymore. I didn’t care. I was just sad.”

Ellie O’Malley, Scarlett’s mom. Oakland, CA:

“She had finished her eighth grade. She had missed everything. She’d missed her graduation. She’d missed this trip to Washington. And then she started her new school [high school] on-line. [She was] very disengaged, never saw people’s faces, no one had the camera on. I mean it was school in like the thinnest most loose [sense] of the word. For the most part it was pretty dire and terrible. By January 2021, she really just no longer had the motivation to do it. She wasn’t getting out of bed. She was really depressed at that point.”

“A lot of it was just mental health, suicidal tendencies, self-harm. The first time Scarlett went to hospital, she kind of had a bit of a nervous breakdown. I’d never experienced that. She was screaming and clawing at herself. And we were like, what do we do? What do we do?”

Miki Sedivy, a mom who lost her teenaged daughter Hannah to an accidental drug overdose in 2021. Lakewood, CO:

“You’re taking children out of their natural environment of playing with each other, interacting socially and learning coping skills by interacting with other children. And when you take all of that away and all of a sudden these kids are in isolation, they mentally don’t know how to handle it. We can go [through] short times of isolation, but we’re talking a year and a half. [That’s] of a lot of isolation.”

Jennifer Dale. Her 11-year-old daughter has Down syndrome. Lake Oswego, OR.

“The school closures were devastating for her. I don’t think I realized it at first. At first I thought it was safer. Lizzie, a child with Down syndrome, was probably more susceptible to a respiratory virus. She’s had more respiratory issues than her siblings. So at first I thought it was the right thing to do As time went on, I don’t think people realized how isolated she was. She doesn’t have a means of reaching out and saying Hey, how you doing? I miss you. I wanna see you.”

“What Lizzie really needs is to look at her peers and how are they zipping up their jacket, or how are they coming in in the morning and making a food selection for lunch. That peer interaction and that peer role modeling is some of the best learning that my daughter can experience. But that role modeling is gone. When you’re online she doesn’t get to see what the other kids are doing. She wasn’t out seeing people. Nobody knew that she was struggling. It was all in our house. It was impossible for a young person with cognitive delays to understand why, why was the world suddenly closed? Why suddenly could I not see my friends? Why am I only seeing them on a screen and how do I interact?”

Am’Brianna Daniels, high school student. San Francisco, CA.

“As time moved on, like later in the year, I started to realize I really wanted to be back in school. I was 24/7 [on Zoom] and I think that’s what took a toll on me. . . I actually stayed doing Zoom in my living room that way I wasn’t tempted to fall asleep or anything. This did not help. I still did fall asleep sometimes.”

“I had like very little motivation to actually get up, get on Zoom and attend class. And then I think coming up on the year anniversary of the initial lockdown and then the lack of social interaction is kind of what took a toll on my mental health since I am such a social person. And so it really got to a point where I was just not going to class.”

“And it got really bad to the point where I was either over-eating or just not eating very much, and I was kind of dehydrated during my depressive moods. And eventually I did get in contact with the therapist. It helped a little bit, but not to the extent that I would have hoped.

Nelson Ropati, high school student. San Francisco, CA.

“I just didn’t like staring at a screen for an hour for class. I just couldn’t do it. I would fall asleep or just lose focus easily.”

“It wasn’t really mandatory to go to class. So I ain’t gonna lie. I didn’t really go to class the rest of my junior year when covid hit and they kind of just passed everyone.”

Lorna Ropati, Nelson’s mom. San Francisco, CA.

“I felt bad for him because then that’s when he started doing nothing else, but just like eating. I said you’re not hungry. It’s just a habit. Don’t go to the fridge. He just mainly stayed home and did whatever he could through his on-line courses and just stayed home. I think he didn’t go out of the house at one point for six months. He didn’t go nowhere. He never even stepped out of the house. So that was not good. I said, you need to get out, you need to stop being in this little shell and bubble that you’re in. It’s okay. You can go out.”

Jim Kuczo, lost his son Kevin to suicide in 2021. Fairfield, CT.

“Well we were very concerned because of the grades — that was the tip off. But again, it was hard because you can’t go out with your friends. We were concerned. We asked the guidance counselor and the therapist, is he suicidal? They said no.”

“You cannot treat kids like prisoners and expect them to be okay. I think that we, our leaders, put most of the burden on children.”

“I went through lots of guilt — what did I do to cause my son to kill himself.”

Kristen Kuczo, Kevin’s mom. Fairfield, CT.

“He [Kevin] wound up not playing football and then we kind of just started noticing he just was doing less and less. His grades were starting to drop. Really the biggest red flag for me was the grades dropping.”

“The day after he took his life, I was supposed to be having a meeting with the guidance counselors and we were looking into getting him a 504, which would allow him extra time to do things and possibly on exams. We were pursuing that as a possibility to try to help support him in the school setting. Because he had spoken to us about having trouble focusing and feeling like he just couldn’t do it.”

“All these doctors, they weren’t taking anybody. They weren’t taking patients because they were full. They didn’t have any space to take on new clients. It was shocking. So I didn’t have an appointment with a psychiatrist until about a week and a half after Kevin passed.”

I’ll leave you with a few words from Garrett Morgan, Jr. He’s struggling to get his life back on track. To get his grades back up. To lose the 80 pounds he gained. To get back in shape. To play football again. To get that college scholarship.

He’s a fighter. And I have confidence he’ll succeed. But he won’t forget what he and his peers lost, what was taken from them, and how much tougher his road ahead is because of it.

“This is something that my generation will not forget. This is also something that my generation will not forgive. The memories that we have lost, the experiences that we have lost, the skills that we have lost because of covid. And now we have to regain that and go out into the world. It is going to be something that will define us.”

Reposted from the author’s Substack

Brownstone Institute

FDA Exposed: Hundreds of Drugs Approved without Proof They Work

From the Brownstone Institute

By

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved hundreds of drugs without proof that they work—and in some cases, despite evidence that they cause harm.

That’s the finding of a blistering two-year investigation by medical journalists Jeanne Lenzer and Shannon Brownlee, published by The Lever.

Reviewing more than 400 drug approvals between 2013 and 2022, the authors found the agency repeatedly ignored its own scientific standards.

One expert put it bluntly—the FDA’s threshold for evidence “can’t go any lower because it’s already in the dirt.”

A System Built on Weak Evidence

The findings were damning—73% of drugs approved by the FDA during the study period failed to meet all four basic criteria for demonstrating “substantial evidence” of effectiveness.

Those four criteria—presence of a control group, replication in two well-conducted trials, blinding of participants and investigators, and the use of clinical endpoints like symptom relief or extended survival—are supposed to be the bedrock of drug evaluation.

Yet only 28% of drugs met all four criteria—40 drugs met none.

These aren’t obscure technicalities—they are the most basic safeguards to protect patients from ineffective or dangerous treatments.

But under political and industry pressure, the FDA has increasingly abandoned them in favour of speed and so-called “regulatory flexibility.”

Since the early 1990s, the agency has relied heavily on expedited pathways that fast-track drugs to market.

In theory, this balances urgency with scientific rigour. In practice, it has flipped the process. Companies can now get drugs approved before proving that they work, with the promise of follow-up trials later.

But, as Lenzer and Brownlee revealed, “Nearly half of the required follow-up studies are never completed—and those that are often fail to show the drugs work, even while they remain on the market.”

“This represents a seismic shift in FDA regulation that has been quietly accomplished with virtually no awareness by doctors or the public,” they added.

More than half the approvals examined relied on preliminary data—not solid evidence that patients lived longer, felt better, or functioned more effectively.

And even when follow-up studies are conducted, many rely on the same flawed surrogate measures rather than hard clinical outcomes.

The result: a regulatory system where the FDA no longer acts as a gatekeeper—but as a passive observer.

Cancer Drugs: High Stakes, Low Standards

Nowhere is this failure more visible than in oncology.

Only 3 out of 123 cancer drugs approved between 2013 and 2022 met all four of the FDA’s basic scientific standards.

Most—81%—were approved based on surrogate endpoints like tumour shrinkage, without any evidence that they improved survival or quality of life.

Take Copiktra, for example—a drug approved in 2018 for blood cancers. The FDA gave it the green light based on improved “progression-free survival,” a measure of how long a tumour stays stable.

But a review of post-marketing data showed that patients taking Copiktra died 11 months earlier than those on a comparator drug.

It took six years after those studies showed the drug reduced patients’ survival for the FDA to warn the public that Copiktra should not be used as a first- or second-line treatment for certain types of leukaemia and lymphoma, citing “an increased risk of treatment-related mortality.”

Elmiron: Ineffective, Dangerous—And Still on the Market

Another striking case is Elmiron, approved in 1996 for interstitial cystitis—a painful bladder condition.

The FDA authorized it based on “close to zero data,” on the condition that the company conduct a follow-up study to determine whether it actually worked.

That study wasn’t completed for 18 years—and when it was, it showed Elmiron was no better than placebo.

In the meantime, hundreds of patients suffered vision loss or blindness. Others were hospitalized with colitis. Some died.

Yet Elmiron is still on the market today. Doctors continue to prescribe it.

“Hundreds of thousands of patients have been exposed to the drug, and the American Urological Association lists it as the only FDA-approved medication for interstitial cystitis,” Lenzer and Brownlee reported.

“Dangling Approvals” and Regulatory Paralysis

The FDA even has a term—”dangling approvals”—for drugs that remain on the market despite failed or missing follow-up trials.

One notorious case is Avastin, approved in 2008 for metastatic breast cancer.

It was fast-tracked, again, based on ‘progression-free survival.’ But after five clinical trials showed no improvement in overall survival—and raised serious safety concerns—the FDA moved to revoke its approval for metastatic breast cancer.

The backlash was intense.

Drug companies and patient advocacy groups launched a campaign to keep Avastin on the market. FDA staff received violent threats. Police were posted outside the agency’s building.

The fallout was so severe that for more than two decades afterwards, the FDA did not initiate another involuntary drug withdrawal in the face of industry opposition.

Billions Wasted, Thousands Harmed

Between 2018 and 2021, US taxpayers—through Medicare and Medicaid—paid $18 billion for drugs approved under the condition that follow-up studies would be conducted. Many never were.

The cost in lives is even higher.

A 2015 study found that 86% of cancer drugs approved between 2008 and 2012 based on surrogate outcomes showed no evidence that they helped patients live longer.

An estimated 128,000 Americans die each year from the effects of properly prescribed medications—excluding opioid overdoses. That’s more than all deaths from illegal drugs combined.

A 2024 analysis by Danish physician Peter Gøtzsche found that adverse effects from prescription medicines now rank among the top three causes of death globally.

Doctors Misled by the Drug Labels

Despite the scale of the problem, most patients—and most doctors—have no idea.

A 2016 survey published in JAMA asked practising physicians a simple question—what does FDA approval actually mean?

Only 6% got it right.

The rest assumed that it meant the drug had shown clear, clinically meaningful benefits—such as helping patients live longer or feel better—and that the data was statistically sound.

But the FDA requires none of that.

Drugs can be approved based on a single small study, a surrogate endpoint, or marginal statistical findings. Labels are often based on limited data, yet many doctors take them at face value.

Harvard researcher Aaron Kesselheim, who led the survey, said the results were “disappointing, but not entirely surprising,” noting that few doctors are taught about how the FDA’s regulatory process actually works.

Instead, physicians often rely on labels, marketing, or assumptions—believing that if the FDA has authorized a drug, it must be both safe and effective.

But as The Lever investigation shows, that is not a safe assumption.

And without that knowledge, even well-meaning physicians may prescribe drugs that do little good—and cause real harm.

Who Is the FDA Working for?

In interviews with more than 100 experts, patients, and former regulators, Lenzer and Brownlee found widespread concern that the FDA has lost its way.

Many pointed to the agency’s dependence on industry money. A BMJ investigation in 2022 found that user fees now fund two-thirds of the FDA’s drug review budget—raising serious questions about independence.

Yale physician and regulatory expert Reshma Ramachandran said the system is in urgent need of reform.

“We need an agency that’s independent from the industry it regulates and that uses high-quality science to assess the safety and efficacy of new drugs,” she told The Lever. “Without that, we might as well go back to the days of snake oil and patent medicines.”

For now, patients remain unwitting participants in a vast, unspoken experiment—taking drugs that may never have been properly tested, trusting a regulator that too often fails to protect them.

And as Lenzer and Brownlee conclude, that trust is increasingly misplaced.

- Investigative report by Jeanne Lenzer and Shannon Brownlee at The Lever [link]

- Searchable public drug approval database [link]

- See my talk: Failure of Drug Regulation: Declining standards and institutional corruption

Republished from the author’s Substack

Brownstone Institute

Anthony Fauci Gets Demolished by White House in New Covid Update

From the Brownstone Institute

By

Anthony Fauci must be furious.

He spent years proudly being the public face of the country’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. He did, however, flip-flop on almost every major issue, seamlessly managing to shift his guidance based on current political whims and an enormous desire to coerce behavior.

Nowhere was this more obvious than his dictates on masks. If you recall, in February 2020, Fauci infamously stated on 60 Minutes that masks didn’t work. That they didn’t provide the protection people thought they did, there were gaps in the fit, and wearing masks could actually make things worse by encouraging wearers to touch their face.

Just a few months later, he did a 180, then backtracked by making up a post-hoc justification for his initial remarks. Laughably, Fauci said that he recommended against masks to protect supply for healthcare workers, as if hospitals would ever buy cloth masks on Amazon like the general public.

Later in interviews, he guaranteed that cities or states that listened to his advice would fare better than those that didn’t. Masks would limit Covid transmission so effectively, he believed, that it would be immediately obvious which states had mandates and which didn’t. It was obvious, but not in the way he expected.

And now, finally, after years of being proven wrong, the White House has officially and thoroughly rebuked Fauci in every conceivable way.

White House Covid Page Points Out Fauci’s Duplicitous Guidance

A new White House official page points out, in detail, exactly where Fauci and the public health expert class went wrong on Covid.

It starts by laying out the case for the lab-leak origin of the coronavirus, with explanations of how Fauci and his partners misled the public by obscuring information and evidence. How they used the “FOIA lady” to hide emails, used private communications to avoid scrutiny, and downplayed the conduct of EcoHealth Alliance because they helped fund it.

They roast the World Health Organization for caving to China and attempting to broaden its powers in the aftermath of “abject failure.”

“The WHO’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic was an abject failure because it caved to pressure from the Chinese Communist Party and placed China’s political interests ahead of its international duties. Further, the WHO’s newest effort to solve the problems exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic — via a “Pandemic Treaty” — may harm the United States,” the site reads.

Social distancing is criticized, correctly pointing out that Fauci testified that there was no scientific data or evidence to support their specific recommendations.

“The ‘6 feet apart’ social distancing recommendation — which shut down schools and small business across the country — was arbitrary and not based on science. During closed door testimony, Dr. Fauci testified that the guidance ‘sort of just appeared.’”

There’s another section demolishing the extended lockdowns that came into effect in blue states like California, Illinois, and New York. Even the initial lockdown, the “15 Days to Slow the Spread,” was a poorly reasoned policy that had no chance of working; extended closures were immensely harmful with no demonstrable benefit.

“Prolonged lockdowns caused immeasurable harm to not only the American economy, but also to the mental and physical health of Americans, with a particularly negative effect on younger citizens. Rather than prioritizing the protection of the most vulnerable populations, federal and state government policies forced millions of Americans to forgo crucial elements of a healthy and financially sound life,” it says.

Then there’s the good stuff: mask mandates. While there’s plenty more detail that could be added, it’s immensely rewarding to see, finally, the truth on an official White House website. Masks don’t work. There’s no evidence supporting mandates, and public health, especially Fauci, flip-flopped without supporting data.

“There was no conclusive evidence that masks effectively protected Americans from COVID-19. Public health officials flipped-flopped on the efficacy of masks without providing Americans scientific data — causing a massive uptick in public distrust.”

This is inarguably true. There were no new studies or data justifying the flip-flop, just wishful thinking and guessing based on results in Asia. It was an inexcusable, world-changing policy that had no basis in evidence, but was treated as equivalent to gospel truth by a willing media and left-wing politicians.

Over time, the CDC and Fauci relied on ridiculous “studies” that were quickly debunked, anecdotes, and ever-shifting goal posts. Wear one cloth mask turned to wear a surgical mask. That turned into “wear two masks,” then wear an N95, then wear two N95s.

All the while ignoring that jurisdictions that tried “high-quality” mask mandates also failed in spectacular fashion.

And that the only high-quality evidence review on masking confirmed no masks worked, even N95s, to prevent Covid transmission, as well as hearing that the CDC knew masks didn’t work anyway.

The website ends with a complete and thorough rebuke of the public health establishment and the Biden administration’s disastrous efforts to censor those who disagreed.

“Public health officials often mislead the American people through conflicting messaging, knee-jerk reactions, and a lack of transparency. Most egregiously, the federal government demonized alternative treatments and disfavored narratives, such as the lab-leak theory, in a shameful effort to coerce and control the American people’s health decisions.

When those efforts failed, the Biden Administration resorted to ‘outright censorship—coercing and colluding with the world’s largest social media companies to censor all COVID-19-related dissent.’”

About time these truths are acknowledged in a public, authoritative manner. Masks don’t work. Lockdowns don’t work. Fauci lied and helped cover up damning evidence.

If only this website had been available years ago.

Though, of course, knowing the media’s political beliefs, they’d have ignored it then, too.

Republished from the author’s Substack

-

Business16 hours ago

Business16 hours agoRFK Jr. says Hep B vaccine is linked to 1,135% higher autism rate

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta Independence Seekers Take First Step: Citizen Initiative Application Approved, Notice of Initiative Petition Issued

-

Crime1 day ago

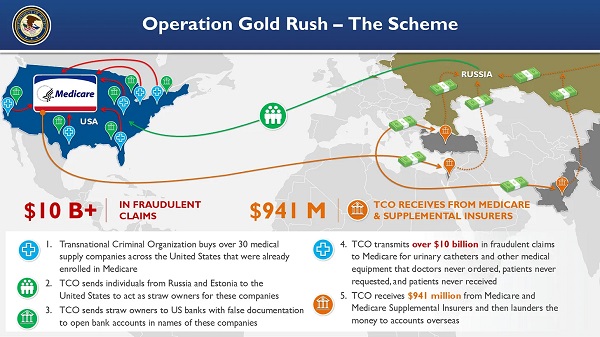

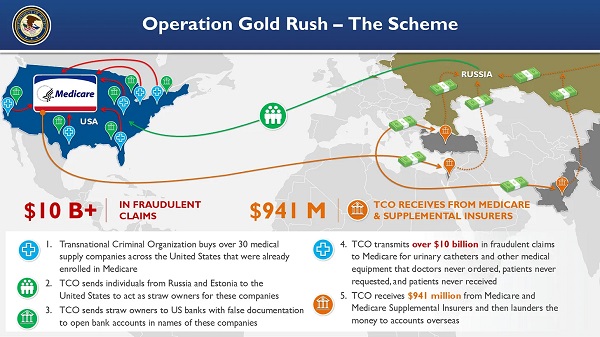

Crime1 day agoNational Health Care Fraud Takedown Results in 324 Defendants Charged in Connection with Over $14.6 Billion in Alleged Fraud

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoSuspected ambush leaves two firefighters dead in Idaho

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoWhy the West’s separatists could be just as big a threat as Quebec’s

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCanada Caves: Carney ditches digital services tax after criticism from Trump

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoRFK Jr. Unloads Disturbing Vaccine Secrets on Tucker—And Surprises Everyone on Trump

-

Censorship Industrial Complex17 hours ago

Censorship Industrial Complex17 hours agoGlobal media alliance colluded with foreign nations to crush free speech in America: House report