Alberta

Fortis et Liber: Alberta’s Future in the Canadian Federation

From the C2C Journal

By Barry Cooper, professor of political science, University of Calgary

Canada’s western lands, wrote one prominent academic, became provinces “in the Roman sense” – acquired possessions that, once vanquished, were there to be exploited. Laurentian Canada regarded the hinterlands as existing primarily to serve the interests of the heartland. And the current holders of office in Ottawa often behave as if the Constitution’s federal-provincial distribution of powers is at best advisory, if it needs to be acknowledged at all. Reviewing this history, Barry Cooper places Alberta’s widely criticized Sovereignty Act in the context of the Prairie provinces’ long struggle for due constitutional recognition and the political equality of their citizens. Canada is a federation, notes Cooper. Provinces do have rights. Constitutions do mean something. And when they are no longer working, they can be changed.

Agriculture

Lacombe meat processor scores $1.2 million dollar provincial tax credit to help expansion

Alberta’s government continues to attract investment and grow the provincial economy.

The province’s inviting and tax-friendly business environment, and abundant agricultural resources, make it one of North America’s best places to do business. In addition, the Agri-Processing Investment Tax Credit helps attract investment that will further diversify Alberta’s agriculture industry.

Beretta Farms is the most recent company to qualify for the tax credit by expanding its existing facility with the potential to significantly increase production capacity. It invested more than $10.9 million in the project that is expected to increase the plant’s processing capacity from 29,583 to 44,688 head of cattle per year. Eleven new employees were hired after the expansion and the company plans to hire ten more. Through the Agri-Processing Investment Tax Credit, Alberta’s government has issued Beretta Farms a tax credit of $1,228,735.

“The Agri-Processing Investment Tax Credit is building on Alberta’s existing competitive advantages for agri-food companies and the primary producers that supply them. This facility expansion will allow Beretta Farms to increase production capacity, which means more Alberta beef across the country, and around the world.”

“This expansion by Beretta Farms is great news for Lacombe and central Alberta. It not only supports local job creation and economic growth but also strengthens Alberta’s global reputation for producing high-quality meat products. I’m proud to see our government supporting agricultural innovation and investment right here in our community.”

The tax credit provides a 12 per cent non-refundable, non-transferable tax credit when businesses invest $10 million or more in a project to build or expand a value-added agri-processing facility in Alberta. The program is open to any food manufacturers and bio processors that add value to commodities like grains or meat or turn agricultural byproducts into new consumer or industrial goods.

Beretta Farms’ facility in Lacombe is a federally registered, European Union-approved harvesting and meat processing facility specializing in the slaughter, processing, packaging and distribution of Canadian and United States cattle and bison meat products to 87 countries worldwide.

“Our recent plant expansion project at our facility in Lacombe has allowed us to increase our processing capacities and add more job opportunities in the central Alberta area. With the support and recognition from the Government of Alberta’s tax credit program, we feel we are in a better position to continue our success and have the confidence to grow our meat brands into the future.”

Alberta’s agri-processing sector is the second-largest manufacturing industry in the province and meat processing plays an important role in the sector, generating millions in annual economic impact and creating thousands of jobs. Alberta continues to be an attractive place for agricultural investment due to its agricultural resources, one of the lowest tax rates in North America, a business-friendly environment and a robust transportation network to connect with international markets.

Quick facts

- Since 2023, there are 16 applicants to the Agri-Processing Investment Tax Credit for projects worth about $1.6 billion total in new investment in Alberta’s agri-processing sector.

- To date, 13 projects have received conditional approval under the program.

- Each applicant must submit progress reports, then apply for a tax credit certificate when the project is complete.

- Beretta Farms has expanded the Lacombe facility by 10,000 square feet to include new warehousing, cooler space and an office building.

- This project has the potential to increase production capacity by 50 per cent, thereby facilitating entry into more European markets.

Related information

Alberta

Alberta Next: Alberta Pension Plan

From Premier Danielle Smith and Alberta.ca/Next

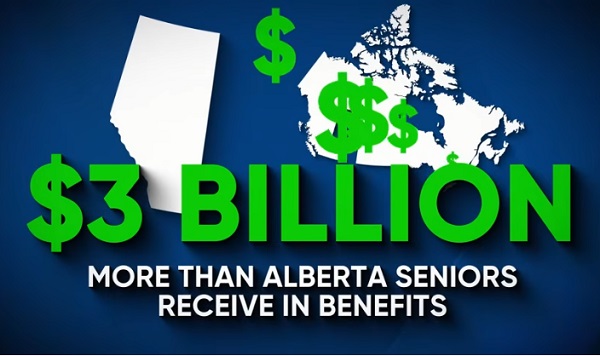

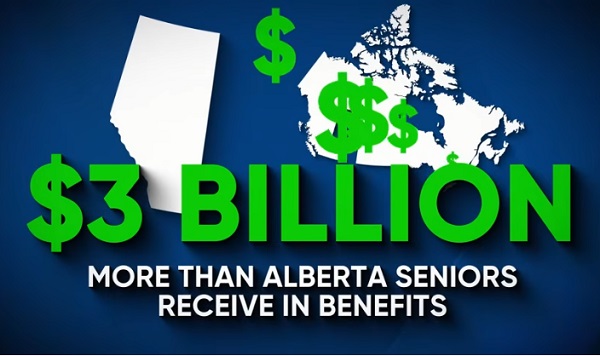

Let’s talk about an Alberta Pension Plan for a minute.

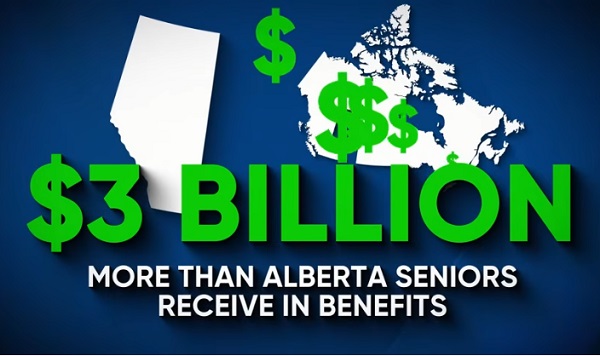

With our young Alberta workforce paying billions more into the CPP each year than our seniors get back in benefits, it’s time to ask whether we stay with the status quo or create our own Alberta Pension Plan that would guarantee as good or better benefits for seniors and lower premiums for workers.

I want to hear your perspective on this idea and please check out the video. Get the facts. Join the conversation.

Visit Alberta.ca/next

-

Energy23 hours ago

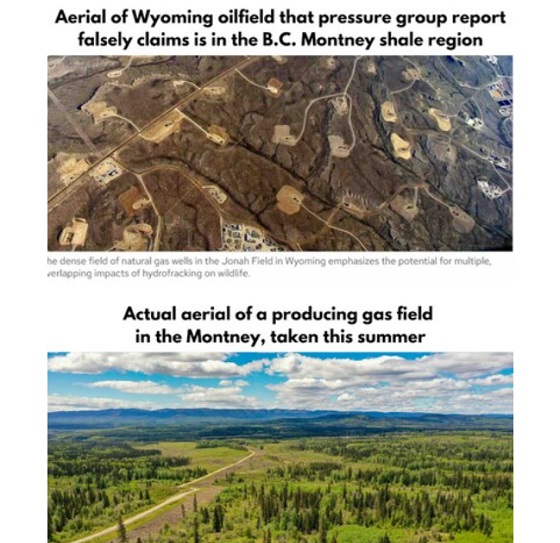

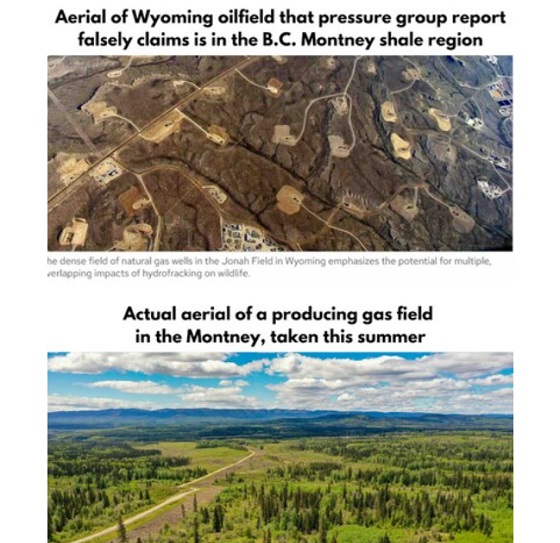

Energy23 hours agoB.C. Residents File Competition Bureau Complaint Against David Suzuki Foundation for Use of False Imagery in Anti-Energy Campaigns

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta uncorks new rules for liquor and cannabis

-

COVID-1923 hours ago

COVID-1923 hours agoCourt compels RCMP and TD Bank to hand over records related to freezing of peaceful protestor’s bank accounts

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoProject Sleeping Giant: Inside the Chinese Mercantile Machine Linking Beijing’s Underground Banks and the Sinaloa Cartel

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoTrump transportation secretary tells governors to remove ‘rainbow crosswalks’

-

C2C Journal21 hours ago

C2C Journal21 hours agoCanada Desperately Needs a Baby Bump

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta Next: Alberta Pension Plan

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney’s spending makes Trudeau look like a cheapskate

For 200 years Rupert’s Land (its flag shown on top left) along with the Northwest and Northeast Territories were the exclusive commercial domain of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), granted by the British Crown; Great Britian officially transferred these vast lands to the Crown in Right of Canada in 1870. (Source of map:

For 200 years Rupert’s Land (its flag shown on top left) along with the Northwest and Northeast Territories were the exclusive commercial domain of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), granted by the British Crown; Great Britian officially transferred these vast lands to the Crown in Right of Canada in 1870. (Source of map:  Obscure but legally important: Canada is often said to have “purchased” Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company, but Canada did not actually pay for the land, only for the company’s capital improvements such as Lower Fort Garry in the Rural Municipality of St. Andrews (aka the Stone Fort, top), Fort Edmonton (middle), depicted here after construction of Alberta’s Legislative Assembly building, and the Hudson’s Bay Brigade Trail (bottom). (Sources of images: (top)

Obscure but legally important: Canada is often said to have “purchased” Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company, but Canada did not actually pay for the land, only for the company’s capital improvements such as Lower Fort Garry in the Rural Municipality of St. Andrews (aka the Stone Fort, top), Fort Edmonton (middle), depicted here after construction of Alberta’s Legislative Assembly building, and the Hudson’s Bay Brigade Trail (bottom). (Sources of images: (top)  “Enter the Union on an equal basis with existing states”: In contrast to Canada, the U.S. Northwest Ordinance of 1787 provided a formal and transparent mechanism by which newly settled territories could graduate to statehood if they met certain conditions – gaining the same rights and privileges as the original 13 states.

“Enter the Union on an equal basis with existing states”: In contrast to Canada, the U.S. Northwest Ordinance of 1787 provided a formal and transparent mechanism by which newly settled territories could graduate to statehood if they met certain conditions – gaining the same rights and privileges as the original 13 states. “Our lives our fortunes and our sacred honour”: Métis leaders Louis Riel (top left) and John Bruce (top right) saw the 1870 transfer of Rubert’s Land to Canada as an act of “abandonment” by the British Crown; to protect the interests of the Red River Settlement (bottom), they “refus[ed] to recognise the authority of Canada.” (Sources: (top left photo) Library and Archives Canada, C-018082; (top right photo)

“Our lives our fortunes and our sacred honour”: Métis leaders Louis Riel (top left) and John Bruce (top right) saw the 1870 transfer of Rubert’s Land to Canada as an act of “abandonment” by the British Crown; to protect the interests of the Red River Settlement (bottom), they “refus[ed] to recognise the authority of Canada.” (Sources: (top left photo) Library and Archives Canada, C-018082; (top right photo)  “Provinces in the Roman sense”: According to political scientist James Mallory, Canada’s Prairie provinces were akin to “provinciae” in ancient Rome – conquered lands whose inhabitants were not citizens and who existed to serve the interests of the Imperial Capital and the Italian heartland. Shown, the fall of Macedonia in 168 BC depicted in The Triumph of Aemilius Paulus by Carle Vernet, 1789. (Source of painting:

“Provinces in the Roman sense”: According to political scientist James Mallory, Canada’s Prairie provinces were akin to “provinciae” in ancient Rome – conquered lands whose inhabitants were not citizens and who existed to serve the interests of the Imperial Capital and the Italian heartland. Shown, the fall of Macedonia in 168 BC depicted in The Triumph of Aemilius Paulus by Carle Vernet, 1789. (Source of painting:  In 1905 the Dominion of Canada carved the new provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan out of portions of the Northwest Territories; the newcomers were treated as distinctly second-class in comparison to the original provinces, among other things only gaining full control over their lands and natural resources in 1930. (Sources of photos (clockwise, starting top-left):

In 1905 the Dominion of Canada carved the new provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan out of portions of the Northwest Territories; the newcomers were treated as distinctly second-class in comparison to the original provinces, among other things only gaining full control over their lands and natural resources in 1930. (Sources of photos (clockwise, starting top-left):  The Prairie provinces continued to be subjected to destructive Laurentian policies throughout the 20th century, such as prolongation of the Canadian Wheat Board, official bilingualism and the National Energy Program, implemented by Pierre Trudeau in 1981 (shown on bottom left, to the right of Alberta premier Peter Lougheed in the centre). Depicted on bottom right, oil sands facility at Mildred Lake. (Sources of photos: (top left) Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau/Library and Archives Canada/C-064834; (bottom left) The Canadian Press/Dave Buston; (bottom right)

The Prairie provinces continued to be subjected to destructive Laurentian policies throughout the 20th century, such as prolongation of the Canadian Wheat Board, official bilingualism and the National Energy Program, implemented by Pierre Trudeau in 1981 (shown on bottom left, to the right of Alberta premier Peter Lougheed in the centre). Depicted on bottom right, oil sands facility at Mildred Lake. (Sources of photos: (top left) Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau/Library and Archives Canada/C-064834; (bottom left) The Canadian Press/Dave Buston; (bottom right)  “It’s not like Ottawa is a national government”: The Alberta Sovereignty within a United Canada Act, passed in late 2022 by the UCP government of Premier Danielle Smith, pictured, aims to strengthen the province’s ability to limit unconstitutional intrusions of federal policy and law into areas of provincial jurisdiction, thereby reaffirming that Canada is a federal state. (Source of photo: The Canadian Press/Jason Franson)

“It’s not like Ottawa is a national government”: The Alberta Sovereignty within a United Canada Act, passed in late 2022 by the UCP government of Premier Danielle Smith, pictured, aims to strengthen the province’s ability to limit unconstitutional intrusions of federal policy and law into areas of provincial jurisdiction, thereby reaffirming that Canada is a federal state. (Source of photo: The Canadian Press/Jason Franson) Although attacked by critics, Alberta’s Sovereignty Act has received strong popular support for challenging the Justin Trudeau government’s constant intrusions into areas of provincial constitutional jurisdiction; the author points out that the Constitution does not require provinces to enforce federal laws, and that the Supreme Court of Canada has confirmed this. Shown, supporters of the Sovereignty Act outside the Alberta legislature, December 2022. (Source of photo:

Although attacked by critics, Alberta’s Sovereignty Act has received strong popular support for challenging the Justin Trudeau government’s constant intrusions into areas of provincial constitutional jurisdiction; the author points out that the Constitution does not require provinces to enforce federal laws, and that the Supreme Court of Canada has confirmed this. Shown, supporters of the Sovereignty Act outside the Alberta legislature, December 2022. (Source of photo:  “Clear majority on a clear question”: Two years after the 1998 Quebec Secession Reference case before the Supreme Court of Canada, the Liberal government of Jean Chrétien (on bottom, leaning forward) introduced the Clarity Act, establishing the conditions under which Canadian provinces may be allowed to begin the process of secession. The author considers this another act violating the concept of federalism, with Ottawa unilaterally calling the shots and placing provinces in a subordinate position. (Sources of photos: (top)

“Clear majority on a clear question”: Two years after the 1998 Quebec Secession Reference case before the Supreme Court of Canada, the Liberal government of Jean Chrétien (on bottom, leaning forward) introduced the Clarity Act, establishing the conditions under which Canadian provinces may be allowed to begin the process of secession. The author considers this another act violating the concept of federalism, with Ottawa unilaterally calling the shots and placing provinces in a subordinate position. (Sources of photos: (top)