Fraser Institute

Federal government should have taken own advice about debt accumulation

From the Fraser Institute

Authors: Grady Munro Jake Fuss

In 2024/25 the federal government now expects to pay $54.1 billion in debt interest, or $1,331 per Canadian, which is $2.0 billion more than it plans to spend on health care transfers to provinces.

In the foreword of the Trudeau government’s recent budget, Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland declared that, “it would be irresponsible and unfair to pass on more debt to the next generations.” Minister Freeland is absolutely right—if only she had listened to her own advice.

Fairness was the purported theme of this federal budget and nearly every new policy is presented as something that will help make life fairer for Canadians—especially younger generations. But the glaring contradiction is that partly due to all of the new spending on these policies, the Trudeau government is doing the very thing it admits is “unfair” and saddling future generations with hundreds of billions in added debt.

By 2027/28, the Trudeau government plans to add $395.6 billion to the total (gross) amount of debt held federally, which is $180.0 billion more than it planned to add just last spring. Overall, gross debt is projected to increase by nearly 20 per cent over the next four years. Adjusting for population growth and inflation during this period, by the end of 2027/28 every Canadian will be responsible for $2,301 more in gross federal debt than they are currently.

Much of this added debt stems from the introduction of new programs, which have caused federal program spending (total spending minus debt interest) over the next four years to be an expected $77.2 billion higher than was forecasted last spring. And though the Trudeau government will increase capital gains taxes to try and pay for this new spending, much of the new spending will still be financed through borrowing. Indeed, combined deficits from 2024/25 to 2027/28 are $44.7 billion higher than forecasted in last year’s budget, and there is no balanced budget in sight at all.

The problem with accumulating substantial amounts of debt, and why Minister Freeland is right when she asserts that it’s “irresponsible and unfair,” is that a growing government debt burden imposes costs on Canadians now and in the future.

One of the most important consequences of government debt are debt interest payments. These interest payments represent taxpayer dollars that don’t go towards any programs or services for Canadians, and have grown to impose a significant burden on federal finances. Specifically, in 2024/25 the federal government now expects to pay $54.1 billion in debt interest, or $1,331 per Canadian, which is $2.0 billion more than it plans to spend on health care transfers to provinces.

While debt interest costs represent a more immediate impact, debt accumulated today must also ultimately be paid for by future generations, again in the form of higher taxes. In fact, research suggests that this effect may be disproportionate, with one dollar borrowed today needing to be paid back by more than one dollar in future taxes.

One study estimates that Canadians aged 16 can expect to pay the equivalent of $29,663 over their lifetime in additional personal income taxes as a consequence of rising federal debt. Older age groups shoulder a much smaller burden in comparison. A 65-year-old can expect to pay $2,433 over their lifetime in additional personal income taxes due to rising federal debt.

The outsized burden of federal debt borne by younger generations of Canadians is hardly what any reasonable person would consider “fair.”

For all its talk about fairness and helping the next generation of Canadians, the Trudeau government’s incessant spending and substantial debt accumulation will simply result in young Canadians paying disproportionately higher taxes in the future. Does that seem fair to you?

Alberta

A Christmas wish list for health-care reform

From the Fraser Institute

By Nadeem Esmail and Mackenzie Moir

It’s an exciting time in Canadian health-care policy. But even the slew of new reforms in Alberta only go part of the way to using all the policy tools employed by high performing universal health-care systems.

For 2026, for the sake of Canadian patients, let’s hope Alberta stays the path on changes to how hospitals are paid and allowing some private purchases of health care, and that other provinces start to catch up.

While Alberta’s new reforms were welcome news this year, it’s clear Canada’s health-care system continued to struggle. Canadians were reminded by our annual comparison of health care systems that they pay for one of the developed world’s most expensive universal health-care systems, yet have some of the fewest physicians and hospital beds, while waiting in some of the longest queues.

And speaking of queues, wait times across Canada for non-emergency care reached the second-highest level ever measured at 28.6 weeks from general practitioner referral to actual treatment. That’s more than triple the wait of the early 1990s despite decades of government promises and spending commitments. Other work found that at least 23,746 patients died while waiting for care, and nearly 1.3 million Canadians left our overcrowded emergency rooms without being treated.

At least one province has shown a genuine willingness to do something about these problems.

The Smith government in Alberta announced early in the year that it would move towards paying hospitals per-patient treated as opposed to a fixed annual budget, a policy approach that Quebec has been working on for years. Albertans will also soon be able purchase, at least in a limited way, some diagnostic and surgical services for themselves, which is again already possible in Quebec. Alberta has also gone a step further by allowing physicians to work in both public and private settings.

While controversial in Canada, these approaches simply mirror what is being done in all of the developed world’s top-performing universal health-care systems. Australia, the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland all pay their hospitals per patient treated, and allow patients the opportunity to purchase care privately if they wish. They all also have better and faster universally accessible health care than Canada’s provinces provide, while spending a little more (Switzerland) or less (Australia, Germany, the Netherlands) than we do.

While these reforms are clearly a step in the right direction, there’s more to be done.

Even if we include Alberta’s reforms, these countries still do some very important things differently.

Critically, all of these countries expect patients to pay a small amount for their universally accessible services. The reasoning is straightforward: we all spend our own money more carefully than we spend someone else’s, and patients will make more informed decisions about when and where it’s best to access the health-care system when they have to pay a little out of pocket.

The evidence around this policy is clear—with appropriate safeguards to protect the very ill and exemptions for lower-income and other vulnerable populations, the demand for outpatient healthcare services falls, reducing delays and freeing up resources for others.

Charging patients even small amounts for care would of course violate the Canada Health Act, but it would also emulate the approach of 100 per cent of the developed world’s top-performing health-care systems. In this case, violating outdated federal policy means better universal health care for Canadians.

These top-performing countries also see the private sector and innovative entrepreneurs as partners in delivering universal health care. A relationship that is far different from the limited individual contracts some provinces have with private clinics and surgical centres to provide care in Canada. In these other countries, even full-service hospitals are operated by private providers. Importantly, partnering with innovative private providers, even hospitals, to deliver universal health care does not violate the Canada Health Act.

So, while Alberta has made strides this past year moving towards the well-established higher performance policy approach followed elsewhere, the Smith government remains at least a couple steps short of truly adopting a more Australian or European approach for health care. And other provinces have yet to even get to where Alberta will soon be.

Let’s hope in 2026 that Alberta keeps moving towards a truly world class universal health-care experience for patients, and that the other provinces catch up.

Environment

Canada’s river water quality strong overall although some localized issues persist

From the Fraser Institute

By Annika Segelhorst and Elmira Aliakbari

Canada’s rivers are vital to our environment and economy. Clean freshwater is essential to support recreation, agriculture and industry, an to sustain suitable habitat for wildlife. Conversely, degraded freshwater can make it harder to maintain safe drinking water and can harm aquatic life. So, how healthy are Canada’s rivers today?

To answer that question, Environment Canada uses an index of water quality to assess freshwater quality at monitoring stations across the country. In total, scores are available for 165 monitoring stations, jointly maintained by Environment Canada and provincial authorities, from 17 in Newfoundland and Labrador, to 8 in Saskatchewan and 20 in British Columbia.

This index works like a report card for rivers, converting water test results into scores from 0 to 100. Scientists sample river water three or more times per year at fixed locations, testing indicators such as oxygen levels, nutrients and chemical levels. These measurements are then compared against national and provincial guidelines that determine the ability of a waterway to support aquatic life.

Scores are calculated based on three factors: how many guidelines are exceeded, how often they are exceeded, and by how much they are exceeded. A score of 95-100 is “excellent,” 80-94 is “good,” 65-79 is “fair,” 45-64 is “marginal” and a score below 45 is “poor.” The most recent scores are based on data from 2021 to 2023.

Among 165 river monitoring sites across the country, the average score was 76.7. Sites along four major rivers earned a perfect score: the Northeast Magaree River (Nova Scotia), the Restigouche River (New Brunswick), the South Saskatchewan River (Saskatchewan) and the Bow River (Alberta). The Bayonne River, a tributary of the St. Lawrence River near Berthierville, Quebec, scored the lowest (33.0).

Overall, between 2021 and 2023, 83.0 per cent of monitoring sites across the country recorded fair to excellent water quality. This is a strong positive signal that most of Canada’s rivers are in generally healthy environmental condition.

A total of 13.3 per cent of stations were deemed to be marginal, that is, they received a score of 45-64 on the index. Only 3.6 per cent of monitoring sites fell into the poor category, meaning that severe degradation was limited to only a few sites (6 of 165).

Monitoring sites along waterways with relatively less development in the river’s headwaters and those with lower population density tended to earn higher scores than sites with developed land uses. However, among the 11 river monitoring sites that rated “excellent,” 8 were situated in areas facing a combination of pressures from nearby human activities that can influence water quality. This indicates the resilience of Canada’s river ecosystems, even in areas facing a combination of multiple stressors from urban runoff, agriculture, and industrial activities where waterways would otherwise be expected to be the most polluted.

Poor or marginal water quality was relatively more common in monitoring sites located along the St. Lawrence River and its major tributaries and near the Great Lakes compared to other regions. Among all sites in the marginal or poor category, 50 per cent were in this area. The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence region is one of the most population-dense and extensively developed parts of Canada, supporting a mix of urban, agricultural, and industrial land uses. These pressures can introduce harmful chemical contaminants and alter nutrient balances in waterways, impairing ecosystem health.

In general, monitoring sites categorized as marginal or poor tended to be located near intensive agriculture and industrial activities. However, it’s important to reiterate that only 28 stations representing 17.0 per cent of all monitoring stations were deemed to be marginal or poor.

Provincial results vary, as shown in the figure below. Water quality scores in Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Saskatchewan and Alberta were, on average, 80 points or higher during the period from 2021 to 2023, indicating that water quality rarely departed from natural or desirable levels.

Rivers sites in Nova Scotia, Ontario, Manitoba and B.C. each had average scores between 74 and 78 points, suggesting occasional departures from natural or desirable levels.

Finally, Quebec’s average river water quality score was 64.5 during the 2021 to 2023 period. This score indicates that water quality departed from ideal conditions more frequently in Quebec than in other provinces, especially compared to provinces like Alberta, Saskatchewan and P.E.I. where no sites rated below “fair.”

Overall, these results highlight Canada’s success in maintaining a generally high quality of water in our rivers. Most waterways are in good shape, though some regions—especially near the Great Lakes and along the St. Lawrence River Valley—continue to face pressures from the combined effects of population growth and intensive land use.

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoGeorgia county admits illegally certifying 315k ballots in 2020 presidential election

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoCommunist China arrests hundreds of Christians just days before Christmas

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe “Disruptor-in-Chief” places Canada in the crosshairs

-

Business22 hours ago

Business22 hours agoSome Of The Wackiest Things Featured In Rand Paul’s New Report Alleging $1,639,135,969,608 In Gov’t Waste

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoCalgary’s new city council votes to ban foreign flags at government buildings

-

Energy12 hours ago

Energy12 hours agoThe Top News Stories That Shaped Canadian Energy in 2025 and Will Continue to Shape Canadian Energy in 2026

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoWarning Canada: China’s Economic Miracle Was Built on Mass Displacement

-

Alberta1 day ago

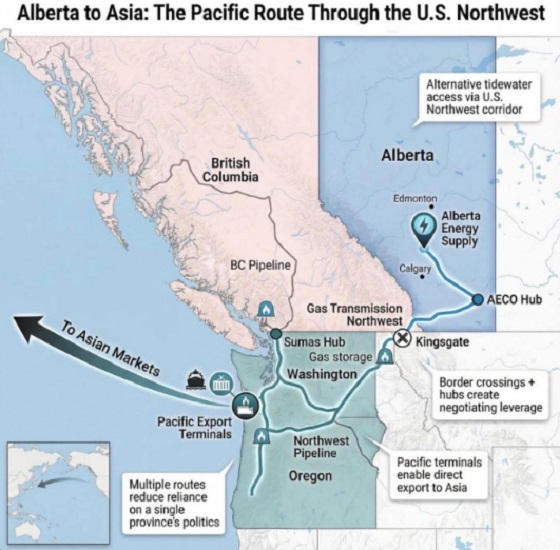

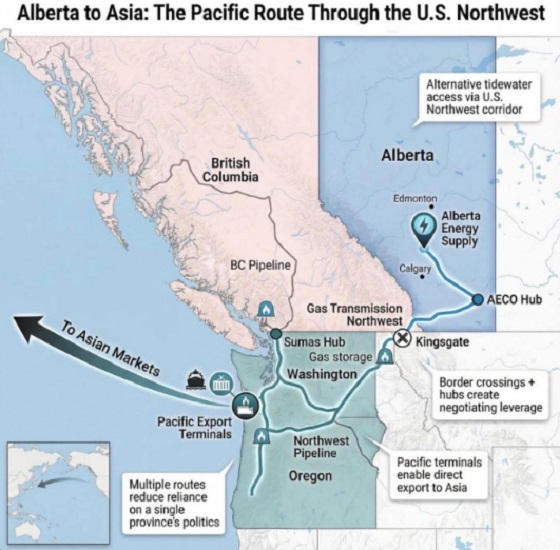

Alberta1 day agoWhat are the odds of a pipeline through the American Pacific Northwest