Brownstone Institute

Et Tu, PayPal? The EU’s Role in Defunding Dissent

This article was originally published by the Brownstone Institute

BY

PayPal appears unsure whether it should participate in the current crusade against online “disinformation” or not.

First it closed the PayPal accounts of The Daily Sceptic and the Free Speech Union, and even the personal account of their founder Toby Young, and then, two weeks later, it restored them. Then it announced that it would be docking $2,500 from anyone who uses its services in connection with “promoting misinformation” and then, two days later, it again reversed course and announced that this language was never intended to be included in its new Acceptable Use Policy (AUP).

It was not intended to be included? Well, where did it come from then?

Could the EU’s Code of Practice on Disinformation and its Digital Services Act (DSA), about which I wrote in my last Brownstone article, have something to do with PayPal’s skittish forays into “combatting disinformation?” Well, yes, they could, and you may rest assured that EU officials or representatives have already had a word with PayPal about them.

As discussed in my previous article, the Code requires signatories to censor what is deemed by the European Commission to be disinformation on pain of massive fines. The enforcement mechanism, i.e. the fines, has been established under the DSA.

PayPal is not, for the moment, a signatory of the Code. Furthermore, since it is neither a content platform nor a search engine – the potential channels of “disinformation” targeted in the DSA – it is obviously not in a position to censor per se. But the very first commitment in the “strengthened” Code of Practice unveiled by the European Commission last June is dedicated precisely to demonetization.

Unsurprisingly, given the nature of the business models of the most prominent signatories – Twitter, Meta/Facebook and Google/YouTube – this commitment and the six “measures” it comprises are mostly related to advertising practices.

But the “Guidance” that the Commission issued in May 2021, prior to the Code’s drafting, explicitly calls for “broadening” efforts to defund alleged purveyors of disinformation and contains the following highly pertinent recommendation:

Actions to defund disinformation should be broadened by the participation of players active in the online monetisation value chain, such as online e-payment services, e-commerce platforms and relevant crowd-funding/donation systems. (p. 8; emphasis added)

PayPal, the online e-payment service par excellence, was thus already in the Commission’s sights.

Somewhat illogically, given their own emphasis on advertising and the fact that an advertising-based revenue model and a donation or pay model would ordinarily be regarded as alternatives, the signatories of the “strengthened” Code thus pledged to

…exchange best practices and strengthen cooperation with relevant players, expanding to organisations active in the online monetisation value chain, such as online e-payment services, e-commerce platforms and relevant crowd-funding/donation systems…. (Commitment 3)

But the outreach to PayPal has not only occurred via third parties like the Code signatories.

In late May, shortly after the text of the Digital Services Act had been finalized – but before the European Parliament had even had the opportunity to vote on it! – an 8-member delegation from the parliament was dispatched to California to discuss the DSA and the related Digital Markets Act (DMA) with relevant “digital stakeholders.”

In addition to Code signatories Google and Meta, the “host list,” so to say – since the parliamentarians were to be the guests and they were inviting themselves! – also included PayPal. (See the delegation report here.)

Curiously, Twitter was not included among the companies and organizations to be visited, perhaps because of the turmoil unleashed by Elon Musk’s takeover bid. But, as touched upon in my prior article, Thierry Breton, the EU’s Internal Market Commissioner, had already paid a visit to Musk in Austin, Texas earlier in the month to have a word with him about the DSA.

No less than three of the delegation’s eight members – Alexandra Geese, Marion Walsmann and delegation head Andreas Schwab – were German, whereas Germans only account for around 13% of the total members of the parliament. This stark overrepresentation is telling, since Germany has undoubtedly been the prime mover behind the EU’s censorship drive, having already adopted its own online censorship law in 2017 with the express motivation of “combatting criminal fake news in social networks” (p. 1 of the legislative proposal in German here).

The German legislation, commonly known as “NetzDG” or the Network Enforcement Act, threatens platforms with fines of up to €50 million for hosting content that infringes any of a variety of German laws that restrict speech in ways that would be unthinkable and unconstitutional in the United States. It is also the source of the Twitter notices that many Twitter users will have received informing them that their account had been denounced by “a person from Germany.”

As noted above, PayPal is not presently a signatory of the Code of Practice on Disinformation. On July 14, however, just nine days after the passage of the DSA, the Commission issued a “Call for interest to become a Signatory” of the Code. The call is explicitly addressed to, among others, “e-payment services, e-commerce platforms, crowd-funding/donation systems.” The latter are identified as “providers whose services may be used to monetize disinformation.”

Evidently not satisfied merely with “deplatforming,” the Commission has thus made clear that the next frontier in its combat against “disinformation” is attempting to defund dissenters who, despite their discrimination by or banishment from the major online platforms, have managed to preserve a place in the online discussion thanks to platforms of their own.

PayPal, moreover, will know that the “exclusive” – in effect, dictatorial – powers that the DSA confers on the European Commission include the power to designate the “very large” online platforms that are susceptible to incurring the massive DSA fines of up to 6% of global turnover. PayPal will easily satisfy the “very large” size criterion of having at least 45 million users in the EU, but it is obviously not a content platform.

Nonetheless, this appears not to be so obvious to the European Commission. For the Commission press release on the call for signatories treats it precisely…as a content platform! Thus, the press release refers to “providers of e-payment services, e-commerce platforms, crowd-funding/donation systems, which may be used to spread disinformation.” Huh?

In the meanwhile, on September 1, the EU has opened a specially-dedicated office or “embassy” in San Francisco to conduct what it itself describes as “digital diplomacy” with US tech firms. The “ambassador,” Commission official Gerard de Graaf, is reportedly one of the drafters of the DSA. Perhaps he will be able to explain the intricacies of the DSA to PayPal – or even already has. PayPal headquarters are, after all, just a stone’s throw away in Palo Alto.

In any case, PayPal has been put on notice, and, with it, so too have dissident websites that depend on user support for their survival. Ignore the EU at your peril.

Brownstone Institute

FDA Exposed: Hundreds of Drugs Approved without Proof They Work

From the Brownstone Institute

By

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved hundreds of drugs without proof that they work—and in some cases, despite evidence that they cause harm.

That’s the finding of a blistering two-year investigation by medical journalists Jeanne Lenzer and Shannon Brownlee, published by The Lever.

Reviewing more than 400 drug approvals between 2013 and 2022, the authors found the agency repeatedly ignored its own scientific standards.

One expert put it bluntly—the FDA’s threshold for evidence “can’t go any lower because it’s already in the dirt.”

A System Built on Weak Evidence

The findings were damning—73% of drugs approved by the FDA during the study period failed to meet all four basic criteria for demonstrating “substantial evidence” of effectiveness.

Those four criteria—presence of a control group, replication in two well-conducted trials, blinding of participants and investigators, and the use of clinical endpoints like symptom relief or extended survival—are supposed to be the bedrock of drug evaluation.

Yet only 28% of drugs met all four criteria—40 drugs met none.

These aren’t obscure technicalities—they are the most basic safeguards to protect patients from ineffective or dangerous treatments.

But under political and industry pressure, the FDA has increasingly abandoned them in favour of speed and so-called “regulatory flexibility.”

Since the early 1990s, the agency has relied heavily on expedited pathways that fast-track drugs to market.

In theory, this balances urgency with scientific rigour. In practice, it has flipped the process. Companies can now get drugs approved before proving that they work, with the promise of follow-up trials later.

But, as Lenzer and Brownlee revealed, “Nearly half of the required follow-up studies are never completed—and those that are often fail to show the drugs work, even while they remain on the market.”

“This represents a seismic shift in FDA regulation that has been quietly accomplished with virtually no awareness by doctors or the public,” they added.

More than half the approvals examined relied on preliminary data—not solid evidence that patients lived longer, felt better, or functioned more effectively.

And even when follow-up studies are conducted, many rely on the same flawed surrogate measures rather than hard clinical outcomes.

The result: a regulatory system where the FDA no longer acts as a gatekeeper—but as a passive observer.

Cancer Drugs: High Stakes, Low Standards

Nowhere is this failure more visible than in oncology.

Only 3 out of 123 cancer drugs approved between 2013 and 2022 met all four of the FDA’s basic scientific standards.

Most—81%—were approved based on surrogate endpoints like tumour shrinkage, without any evidence that they improved survival or quality of life.

Take Copiktra, for example—a drug approved in 2018 for blood cancers. The FDA gave it the green light based on improved “progression-free survival,” a measure of how long a tumour stays stable.

But a review of post-marketing data showed that patients taking Copiktra died 11 months earlier than those on a comparator drug.

It took six years after those studies showed the drug reduced patients’ survival for the FDA to warn the public that Copiktra should not be used as a first- or second-line treatment for certain types of leukaemia and lymphoma, citing “an increased risk of treatment-related mortality.”

Elmiron: Ineffective, Dangerous—And Still on the Market

Another striking case is Elmiron, approved in 1996 for interstitial cystitis—a painful bladder condition.

The FDA authorized it based on “close to zero data,” on the condition that the company conduct a follow-up study to determine whether it actually worked.

That study wasn’t completed for 18 years—and when it was, it showed Elmiron was no better than placebo.

In the meantime, hundreds of patients suffered vision loss or blindness. Others were hospitalized with colitis. Some died.

Yet Elmiron is still on the market today. Doctors continue to prescribe it.

“Hundreds of thousands of patients have been exposed to the drug, and the American Urological Association lists it as the only FDA-approved medication for interstitial cystitis,” Lenzer and Brownlee reported.

“Dangling Approvals” and Regulatory Paralysis

The FDA even has a term—”dangling approvals”—for drugs that remain on the market despite failed or missing follow-up trials.

One notorious case is Avastin, approved in 2008 for metastatic breast cancer.

It was fast-tracked, again, based on ‘progression-free survival.’ But after five clinical trials showed no improvement in overall survival—and raised serious safety concerns—the FDA moved to revoke its approval for metastatic breast cancer.

The backlash was intense.

Drug companies and patient advocacy groups launched a campaign to keep Avastin on the market. FDA staff received violent threats. Police were posted outside the agency’s building.

The fallout was so severe that for more than two decades afterwards, the FDA did not initiate another involuntary drug withdrawal in the face of industry opposition.

Billions Wasted, Thousands Harmed

Between 2018 and 2021, US taxpayers—through Medicare and Medicaid—paid $18 billion for drugs approved under the condition that follow-up studies would be conducted. Many never were.

The cost in lives is even higher.

A 2015 study found that 86% of cancer drugs approved between 2008 and 2012 based on surrogate outcomes showed no evidence that they helped patients live longer.

An estimated 128,000 Americans die each year from the effects of properly prescribed medications—excluding opioid overdoses. That’s more than all deaths from illegal drugs combined.

A 2024 analysis by Danish physician Peter Gøtzsche found that adverse effects from prescription medicines now rank among the top three causes of death globally.

Doctors Misled by the Drug Labels

Despite the scale of the problem, most patients—and most doctors—have no idea.

A 2016 survey published in JAMA asked practising physicians a simple question—what does FDA approval actually mean?

Only 6% got it right.

The rest assumed that it meant the drug had shown clear, clinically meaningful benefits—such as helping patients live longer or feel better—and that the data was statistically sound.

But the FDA requires none of that.

Drugs can be approved based on a single small study, a surrogate endpoint, or marginal statistical findings. Labels are often based on limited data, yet many doctors take them at face value.

Harvard researcher Aaron Kesselheim, who led the survey, said the results were “disappointing, but not entirely surprising,” noting that few doctors are taught about how the FDA’s regulatory process actually works.

Instead, physicians often rely on labels, marketing, or assumptions—believing that if the FDA has authorized a drug, it must be both safe and effective.

But as The Lever investigation shows, that is not a safe assumption.

And without that knowledge, even well-meaning physicians may prescribe drugs that do little good—and cause real harm.

Who Is the FDA Working for?

In interviews with more than 100 experts, patients, and former regulators, Lenzer and Brownlee found widespread concern that the FDA has lost its way.

Many pointed to the agency’s dependence on industry money. A BMJ investigation in 2022 found that user fees now fund two-thirds of the FDA’s drug review budget—raising serious questions about independence.

Yale physician and regulatory expert Reshma Ramachandran said the system is in urgent need of reform.

“We need an agency that’s independent from the industry it regulates and that uses high-quality science to assess the safety and efficacy of new drugs,” she told The Lever. “Without that, we might as well go back to the days of snake oil and patent medicines.”

For now, patients remain unwitting participants in a vast, unspoken experiment—taking drugs that may never have been properly tested, trusting a regulator that too often fails to protect them.

And as Lenzer and Brownlee conclude, that trust is increasingly misplaced.

- Investigative report by Jeanne Lenzer and Shannon Brownlee at The Lever [link]

- Searchable public drug approval database [link]

- See my talk: Failure of Drug Regulation: Declining standards and institutional corruption

Republished from the author’s Substack

Brownstone Institute

Anthony Fauci Gets Demolished by White House in New Covid Update

From the Brownstone Institute

By

Anthony Fauci must be furious.

He spent years proudly being the public face of the country’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. He did, however, flip-flop on almost every major issue, seamlessly managing to shift his guidance based on current political whims and an enormous desire to coerce behavior.

Nowhere was this more obvious than his dictates on masks. If you recall, in February 2020, Fauci infamously stated on 60 Minutes that masks didn’t work. That they didn’t provide the protection people thought they did, there were gaps in the fit, and wearing masks could actually make things worse by encouraging wearers to touch their face.

Just a few months later, he did a 180, then backtracked by making up a post-hoc justification for his initial remarks. Laughably, Fauci said that he recommended against masks to protect supply for healthcare workers, as if hospitals would ever buy cloth masks on Amazon like the general public.

Later in interviews, he guaranteed that cities or states that listened to his advice would fare better than those that didn’t. Masks would limit Covid transmission so effectively, he believed, that it would be immediately obvious which states had mandates and which didn’t. It was obvious, but not in the way he expected.

And now, finally, after years of being proven wrong, the White House has officially and thoroughly rebuked Fauci in every conceivable way.

White House Covid Page Points Out Fauci’s Duplicitous Guidance

A new White House official page points out, in detail, exactly where Fauci and the public health expert class went wrong on Covid.

It starts by laying out the case for the lab-leak origin of the coronavirus, with explanations of how Fauci and his partners misled the public by obscuring information and evidence. How they used the “FOIA lady” to hide emails, used private communications to avoid scrutiny, and downplayed the conduct of EcoHealth Alliance because they helped fund it.

They roast the World Health Organization for caving to China and attempting to broaden its powers in the aftermath of “abject failure.”

“The WHO’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic was an abject failure because it caved to pressure from the Chinese Communist Party and placed China’s political interests ahead of its international duties. Further, the WHO’s newest effort to solve the problems exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic — via a “Pandemic Treaty” — may harm the United States,” the site reads.

Social distancing is criticized, correctly pointing out that Fauci testified that there was no scientific data or evidence to support their specific recommendations.

“The ‘6 feet apart’ social distancing recommendation — which shut down schools and small business across the country — was arbitrary and not based on science. During closed door testimony, Dr. Fauci testified that the guidance ‘sort of just appeared.’”

There’s another section demolishing the extended lockdowns that came into effect in blue states like California, Illinois, and New York. Even the initial lockdown, the “15 Days to Slow the Spread,” was a poorly reasoned policy that had no chance of working; extended closures were immensely harmful with no demonstrable benefit.

“Prolonged lockdowns caused immeasurable harm to not only the American economy, but also to the mental and physical health of Americans, with a particularly negative effect on younger citizens. Rather than prioritizing the protection of the most vulnerable populations, federal and state government policies forced millions of Americans to forgo crucial elements of a healthy and financially sound life,” it says.

Then there’s the good stuff: mask mandates. While there’s plenty more detail that could be added, it’s immensely rewarding to see, finally, the truth on an official White House website. Masks don’t work. There’s no evidence supporting mandates, and public health, especially Fauci, flip-flopped without supporting data.

“There was no conclusive evidence that masks effectively protected Americans from COVID-19. Public health officials flipped-flopped on the efficacy of masks without providing Americans scientific data — causing a massive uptick in public distrust.”

This is inarguably true. There were no new studies or data justifying the flip-flop, just wishful thinking and guessing based on results in Asia. It was an inexcusable, world-changing policy that had no basis in evidence, but was treated as equivalent to gospel truth by a willing media and left-wing politicians.

Over time, the CDC and Fauci relied on ridiculous “studies” that were quickly debunked, anecdotes, and ever-shifting goal posts. Wear one cloth mask turned to wear a surgical mask. That turned into “wear two masks,” then wear an N95, then wear two N95s.

All the while ignoring that jurisdictions that tried “high-quality” mask mandates also failed in spectacular fashion.

And that the only high-quality evidence review on masking confirmed no masks worked, even N95s, to prevent Covid transmission, as well as hearing that the CDC knew masks didn’t work anyway.

The website ends with a complete and thorough rebuke of the public health establishment and the Biden administration’s disastrous efforts to censor those who disagreed.

“Public health officials often mislead the American people through conflicting messaging, knee-jerk reactions, and a lack of transparency. Most egregiously, the federal government demonized alternative treatments and disfavored narratives, such as the lab-leak theory, in a shameful effort to coerce and control the American people’s health decisions.

When those efforts failed, the Biden Administration resorted to ‘outright censorship—coercing and colluding with the world’s largest social media companies to censor all COVID-19-related dissent.’”

About time these truths are acknowledged in a public, authoritative manner. Masks don’t work. Lockdowns don’t work. Fauci lied and helped cover up damning evidence.

If only this website had been available years ago.

Though, of course, knowing the media’s political beliefs, they’d have ignored it then, too.

Republished from the author’s Substack

-

Agriculture2 days ago

Agriculture2 days agoCanada’s supply management system is failing consumers

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta uncorks new rules for liquor and cannabis

-

Energy20 hours ago

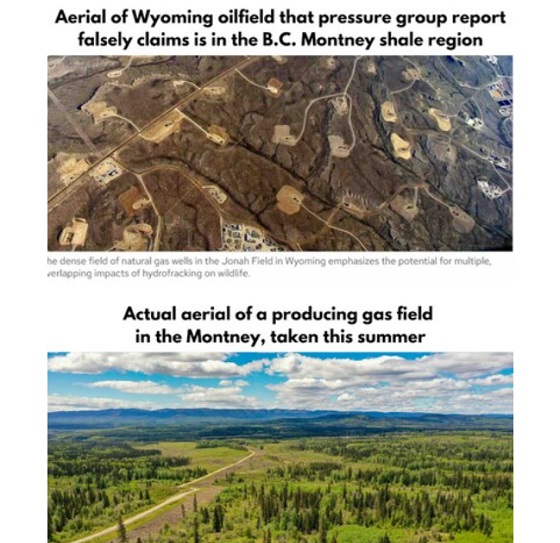

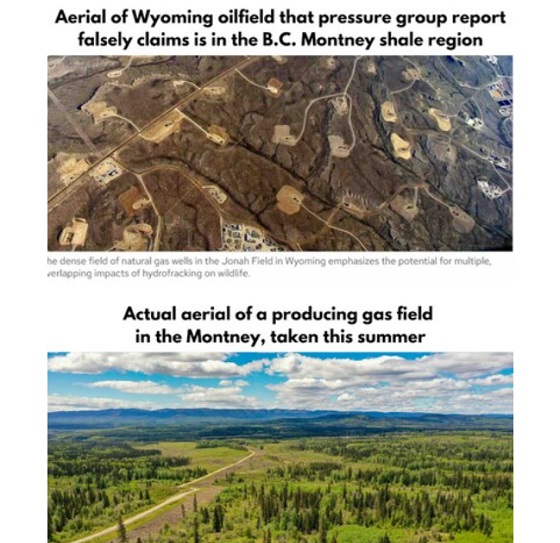

Energy20 hours agoB.C. Residents File Competition Bureau Complaint Against David Suzuki Foundation for Use of False Imagery in Anti-Energy Campaigns

-

COVID-1919 hours ago

COVID-1919 hours agoCourt compels RCMP and TD Bank to hand over records related to freezing of peaceful protestor’s bank accounts

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day agoProject Sleeping Giant: Inside the Chinese Mercantile Machine Linking Beijing’s Underground Banks and the Sinaloa Cartel

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoTrump transportation secretary tells governors to remove ‘rainbow crosswalks’

-

Alberta23 hours ago

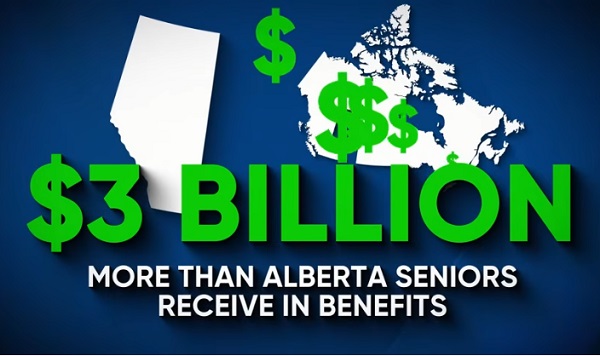

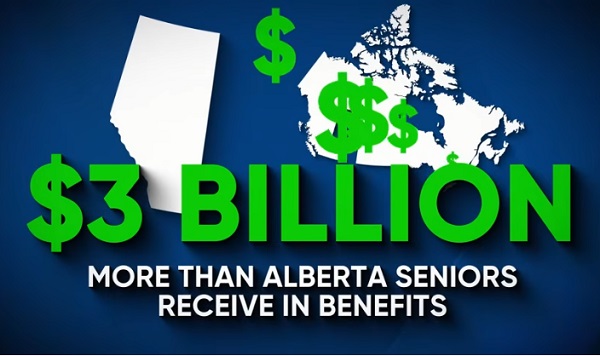

Alberta23 hours agoAlberta Next: Alberta Pension Plan

-

C2C Journal17 hours ago

C2C Journal17 hours agoCanada Desperately Needs a Baby Bump