Fraser Institute

Dearth of medical resources harms Canadian patients

From the Fraser Institute

The imbalance between high spending and poor access to doctors, hospital beds and vital imaging technology, coupled with untimely access to services, can, and does, have a detrimental impact on patients.

Whether it’s a lack of family physicians or other health-care workers, Canadians know we have a serious health-care labour shortage on our hands. The implications of this shortage aren’t lost on patients (including Ellie O’Brien) who’ve possibly faced delays in accessing organ transplants because potential donors need a regular family doctor to screen them to begin the transplant process.

Given these access issues, coupled with some of the longest recorded wait times for medical procedures on record, is it any wonder that Canadians are dissatisfied with how their provincial governments handle health care?

While one instinct might be to demand governments spend more on health care, it’s not clear we’re getting good value in return for what’s already being spent. In fact, compared to 29 other high-income countries with universal health care, Canada spent the most on health care as a share of the economy at 12.6 per cent in 2021, the latest year of available comparable data (after adjusting for differences in the age structure of each country’s population).

But what do we get in return for this spending?

As far as medical resources go, not a whole lot. In 2021, Canadians had some of the fewest medical resources in the developed world. Out of 30 high-income countries with universal health care, Canada ranked 28th on physician availability at 2.8 per 1,000 people, far behind countries such as seventh-ranked Switzerland (4.5 physicians per 1,000) and tenth-ranked Australia (at 4.3 physicians per 1,000).

But doctors are just one part of the puzzle. Canada also ranked low on available hospital beds (23rd of 29 countries), meaning patients often face delays for hospital care. It can also mean that patients end up being treated for their illness outside a traditional patient room—such as a hospital hallway, a phenomenon that has spread to many provinces.

We also see a low availability of other key medical resources including diagnostic equipment. In 2019, Canada ranked 25th of 29 comparable countries with universal health care on the number of MRIs (10.3 units per million people) compared to top-ranked Japan, which had four times as many MRIs as Canada. And we ranked 26th out of 30 countries on CT scanners (14.9 scanners per million people) compared to second-ranked Australia, which had five times as many CT scanners. It’s also worth noting that a large a portion of Canada’s diagnostic machines are remarkably old.

It’s no accident that countries such as Australia, which actually spend less of its economy on health care compared to Canada, perform better than Canada on measures of resource availability and timeliness of care. Unlike Canada, Australia embraces its private sector as an integral part of its universal health-care system. With 41 per cent of all hospital care in Australia occurring in private hospitals in 2021/22, private hospitals can act as a pressure valve for the entire system, particularly in times of crisis. Indeed, the country outperforms Canada on measures of timely access to family doctor appointments, specialist care and non-emergency surgery, and has done so regularly for years.

The imbalance between high spending and poor access to doctors, hospital beds and vital imaging technology, coupled with untimely access to services, can, and does, have a detrimental impact on patients. For some, this problem can be life threatening. Without genuine reform based on real world lessons from higher performing universal health-care countries including Australia, it’s impossible to reasonably expect our health-care system to improve despite its hefty price tag.

Author:

Fraser Institute

Long waits for health care hit Canadians in their pocketbooks

From the Fraser Institute

Canadians continue to endure long wait times for health care. And while waiting for care can obviously be detrimental to your health and wellbeing, it can also hurt your pocketbook.

In 2024, the latest year of available data, the median wait—from referral by a family doctor to treatment by a specialist—was 30 weeks (including 15 weeks waiting for treatment after seeing a specialist). And last year, an estimated 1.5 million Canadians were waiting for care.

It’s no wonder Canadians are frustrated with the current state of health care.

Again, long waits for care adversely impact patients in many different ways including physical pain, psychological distress and worsened treatment outcomes as lengthy waits can make the treatment of some problems more difficult. There’s also a less-talked about consequence—the impact of health-care waits on the ability of patients to participate in day-to-day life, work and earn a living.

According to a recent study published by the Fraser Institute, wait times for non-emergency surgery cost Canadian patients $5.2 billion in lost wages in 2024. That’s about $3,300 for each of the 1.5 million patients waiting for care. Crucially, this estimate only considers time at work. After also accounting for free time outside of work, the cost increases to $15.9 billion or more than $10,200 per person.

Of course, some advocates of the health-care status quo argue that long waits for care remain a necessary trade-off to ensure all Canadians receive universal health-care coverage. But the experience of many high-income countries with universal health care shows the opposite.

Despite Canada ranking among the highest spenders (4th of 31 countries) on health care (as a percentage of its economy) among other developed countries with universal health care, we consistently rank among the bottom for the number of doctors, hospital beds, MRIs and CT scanners. Canada also has one of the worst records on access to timely health care.

So what do these other countries do differently than Canada? In short, they embrace the private sector as a partner in providing universal care.

Australia, for instance, spends less on health care (again, as a percentage of its economy) than Canada, yet the percentage of patients in Australia (33.1 per cent) who report waiting more than two months for non-emergency surgery was much higher in Canada (58.3 per cent). Unlike in Canada, Australian patients can choose to receive non-emergency surgery in either a private or public hospital. In 2021/22, 58.6 per cent of non-emergency surgeries in Australia were performed in private hospitals.

But we don’t need to look abroad for evidence that the private sector can help reduce wait times by delivering publicly-funded care. From 2010 to 2014, the Saskatchewan government, among other policies, contracted out publicly-funded surgeries to private clinics and lowered the province’s median wait time from one of the longest in the country (26.5 weeks in 2010) to one of the shortest (14.2 weeks in 2014). The initiative also reduced the average cost of procedures by 26 per cent.

Canadians are waiting longer than ever for health care, and the economic costs of these waits have never been higher. Until policymakers have the courage to enact genuine reform, based in part on more successful universal health-care systems, this status quo will continue to cost Canadian patients.

Business

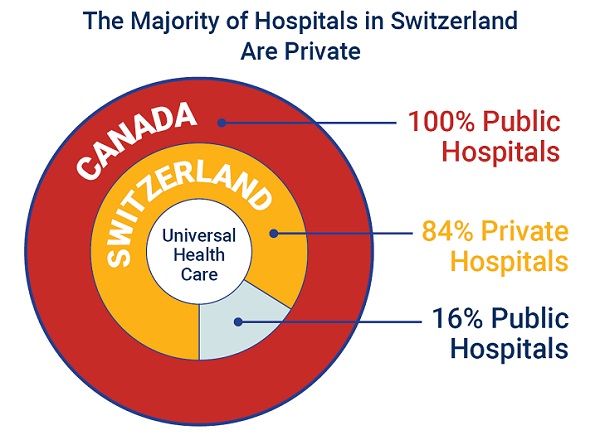

84% of Swiss hospitals and 60% of hospitalizations are in private facilities, and they face much lower wait times

From the Fraser Institute

If Canada reformed to emulate Switzerland’s approach to universal health care, including its much greater use of private sector involvement, the country would deliver far better results to patients and reduce wait times, finds a new study published today by the Fraser Institute, an independent, non-partisan Canadian policy think-tank.

“The bane of Canadian health care is lack of access to timely care, so it’s critical to look to countries like Switzerland with more successful universal health care,” said Yanick Labrie, senior fellow at the Fraser Institute and author of Integrating Private Health Care Into Canada’s Public System: What We Can Learn from Switzerland. The study highlights how Switzerland successfully integrates the private sector into their universal health-care system, which consistently outperforms Canada on most health-care metrics, including wait times.

For example, in 2022, the percentage of patients who waited less than two months for a specialist appointment was 85.3 per cent in Switzerland compared to just 48.3 per cent in Canada.

In Switzerland, 84.2 per cent of all hospitals are private (either for-profit or not-for profit) institutions, and the country’s private hospitals provide 60.2 per cent of all hospitalizations, 60.9 per cent of all births, and 67.1 per cent of all operating rooms.

Crucially, Swiss patients can obtain treatment at the hospital of their choice, whether located inside or outside their geographic location, and hospitals cannot discriminate against patients, based on the care required.

“Switzerland shows that a universal health-care system can reconcile efficiency and equity–all while being more accessible and responsive to patients’ needs and preferences,” Labrie said.

“Based on the success of the Swiss model, provinces can make these reforms now and help improve Canadian health care.”

Integrating Private Health Care into Canada’s Public System: What We Can Learn from Switzerland

- Access to timely care remains the Achilles’ heel of Canada’s health systems. To reduce wait times, some provinces have partnered with private clinics for publicly funded surgeries—a strategy that has proven effective, but continues to spark debate in Canada.

- This study explores how Switzerland successfully integrates private health care into a universal public system and considers what Canada can learn from this model.

- In Switzerland, universal coverage is delivered through a system of managed competition among 44 non-profit private insurers, while decentralized governance allows each of the 26 cantons to coordinate and oversee hospital services in ways that reflect local needs and priorities.

- Nearly two-thirds of Swiss hospitals are for-profit institutions; they provide roughly half of all hospitalizations, births, and hospital beds across the country.

- All hospitals are treated equally—regardless of legal status—and funded through the same activity-based model, implemented nationwide in 2012.

- The reform led to a significant increase in the number of cases treated without a corresponding rise in expenditures per case, suggesting improved efficiency, better use of resources, and expanded access to hospital care.

- The average length of hospital stay steadily decreased over time and now stands at 4.87 days in for-profit hospitals versus 5.53 days in public ones, indicating faster patient turnover and more streamlined care pathways.

- Hospital-acquired infection rates are significantly lower in private hospitals (2.7%) than in public hospitals (6.2%), a key indicator of care quality.

- Case-mix severity is as high or higher in private hospitals, countering the notion that they only take on simpler or less risky cases.

- Patient satisfaction is slightly higher in private hospitals (4.28/5) than in public ones (4.17/5), reflecting strong user experience across multiple dimensions.

- Canada could benefit from regulated competition between public and private providers and activity-based funding, without breaching the Canada Health Act.