Brownstone Institute

CRTC’s podcast rules mean the days of enjoying a free and open internet are over: Former CRTC vice-chair Peter Menzies

From the MacDonald Laurier Institute

By Peter Menzies

Podcasters need to be afraid that what the CRTC is going to come up with is a set of rules governing the transmission of podcasts by the likes of YouTube, Spotify, and any other platform with revenue of more than $10 million.

Perhaps you like listening to podcasts produced by the likes of Ben Shapiro, Jordan Peterson, and Joe Rogan.

Maybe you lean to the left and tune in to the rabble.ca podcasting network in Canada or, in the States, Al Franken.

You might not even be into politics at all. Your interests might focus on food, fashion, travel, celebrity news, movies, or music.

Here’s something you need to know: Going forward, all your favourite podcasts will be transmitted and overseen under the keen regulatory eye of the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) and its nine cabinet appointees.

Your days of enjoying a free and open internet are over.

That’s because the CRTC declared, in its first decisions since being granted authority over the global internet through the Online Streaming Act (Bill C-11), that podcasts meet its definition of “programming.” That means, according to the federal regulator, that the transmission of such “programming” constitutes “broadcasting” which in turn leads to the definition of any platform distributing podcasts as a broadcasting distributor, which most of us know as a cable company.

So, thanks to all that regulatory legerdemain, platforms that distribute podcasts must now register with the CRTC so that it can decide how, in the words of Heritage Minister Pascale St-Onge, to “best support” podcasts.

You will hear a lot in the weeks and months to come from St-Onge and CRTC Chair Vicky Eatrides about how they won’t be regulating podcasters—absolutely not!—and their content, just like they “don’t regulate” television and radio programs.

They may even honestly believe that. If they do, they are living in a world of self-delusion and denial; virtually everything the CRTC does in terms of broadcasting dictates the terms and conditions under which those programs are allowed to exist.

Broadcasting licences detail—in many cases to the minute—what sort of programming will be transmitted, when, and in what proportion. And—here’s the crunch—it is the CRTC’s responsibility under its governing legislation to make sure “the programming over which a person who carries on a broadcasting undertaking has programming control should be of high standard”—as subjective a measure as is imaginable.

To meet that obligation while avoiding getting the regulator’s hands dirty, the radio and television industry “volunteered” decades ago to “self-regulate” through the Canadian Broadcast Standards Council (CBSC), to which virtually all radio and television operators except for the CBC belong.

The CBSC’s most notable decision of late was its somewhat grudging acceptance—despite the complaint lodged by a single viewer outraged by its racism and misogyny—that CHCH-TV’s “Happy Days” reruns did not violate its code despite there being “no doubt that some components of the program may not be pleasant for some viewers.”

It also famously—again, based on a complaint from a single listener—declared that the Dire Straits iconic 1985 song “Money For Nothing” could no longer be played because one of the characters portrayed through its parody lyrics uses a homophobic slur. You may agree with this or you may disagree. But it is, without question, censorship.

The CBSC’s code of conduct is overseen by the CRTC, to which it files an annual report, and its decisions regarding complaints can be appealed to the commission. As it proved when it sanctioned Radio-Canada for allowing the N-word to be spoken on air, the CRTC doesn’t hesitate to assume the role of censor when called upon to do so.

Censorship is a business it has been in for decades.

The organization just prefers to do it by stealth, which is why podcasters need to be afraid—very afraid—that what the CRTC is going to come up with is a set of rules governing the transmission of podcasts by the likes of YouTube, Spotify, and any other platform with revenue of more than $10 million. There is no reason to expect this will unfold much differently than it did with the creation of the CBSC, which established a system of self-censorship that has hovered over Canadian broadcasters since 1991.

Don’t take just my word for it.

“Broadcasters in this country have a long history of self-censorship, whether through the ‘independent’ Canadian Broadcast Standards Council or just in the privacy of their own head offices,” wrote Globe and Mail columnist and CBC panelist Andrew Coyne recently when assessing the CRTC’s podcast decision. “And now we can look forward to the same online.”

What Canadians have been experiencing through their CRTC-governed and controlled broadcasting system is an arrangement through which the scope of opinion, the range of perspectives, and the manner in which they are expressed are carefully and meticulously curated. This is done through an unspoken but deeply embedded mutual understanding between the regulator and broadcasting companies. You, as a consumer of content, have no say.

They think that’s fine. It’s really all they know.

I don’t think that’s fine. Not at all. And, if you value your freedom, neither should you.

Peter Menzies is a senior fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, an award winning journalist, and former vice-chair of the CRTC.

Brownstone Institute

The Unmasking of Vaccine Science

From the Brownstone Institute

By

I recently purchased Aaron Siri’s new book Vaccines, Amen. As I flipped though the pages, I noticed a section devoted to his now-famous deposition of Dr Stanley Plotkin, the “godfather” of vaccines.

I’d seen viral clips circulating on social media, but I had never taken the time to read the full transcript — until now.

Siri’s interrogation was methodical and unflinching…a masterclass in extracting uncomfortable truths.

A Legal Showdown

In January 2018, Dr Stanley Plotkin, a towering figure in immunology and co-developer of the rubella vaccine, was deposed under oath in Pennsylvania by attorney Aaron Siri.

The case stemmed from a custody dispute in Michigan, where divorced parents disagreed over whether their daughter should be vaccinated. Plotkin had agreed to testify in support of vaccination on behalf of the father.

What followed over the next nine hours, captured in a 400-page transcript, was extraordinary.

Plotkin’s testimony revealed ethical blind spots, scientific hubris, and a troubling indifference to vaccine safety data.

He mocked religious objectors, defended experiments on mentally disabled children, and dismissed glaring weaknesses in vaccine surveillance systems.

A System Built on Conflicts

From the outset, Plotkin admitted to a web of industry entanglements.

He confirmed receiving payments from Merck, Sanofi, GSK, Pfizer, and several biotech firms. These were not occasional consultancies but long-standing financial relationships with the very manufacturers of the vaccines he promoted.

Plotkin appeared taken aback when Siri questioned his financial windfall from royalties on products like RotaTeq, and expressed surprise at the “tone” of the deposition.

Siri pressed on: “You didn’t anticipate that your financial dealings with those companies would be relevant?”

Plotkin replied: “I guess, no, I did not perceive that that was relevant to my opinion as to whether a child should receive vaccines.”

The man entrusted with shaping national vaccine policy had a direct financial stake in its expansion, yet he brushed it aside as irrelevant.

Contempt for Religious Dissent

Siri questioned Plotkin on his past statements, including one in which he described vaccine critics as “religious zealots who believe that the will of God includes death and disease.”

Siri asked whether he stood by that statement. Plotkin replied emphatically, “I absolutely do.”

Plotkin was not interested in ethical pluralism or accommodating divergent moral frameworks. For him, public health was a war, and religious objectors were the enemy.

He also admitted to using human foetal cells in vaccine production — specifically WI-38, a cell line derived from an aborted foetus at three months’ gestation.

Siri asked if Plotkin had authored papers involving dozens of abortions for tissue collection. Plotkin shrugged: “I don’t remember the exact number…but quite a few.”

Plotkin regarded this as a scientific necessity, though for many people — including Catholics and Orthodox Jews — it remains a profound moral concern.

Rather than acknowledging such sensitivities, Plotkin dismissed them outright, rejecting the idea that faith-based values should influence public health policy.

That kind of absolutism, where scientific aims override moral boundaries, has since drawn criticism from ethicists and public health leaders alike.

As NIH director Jay Bhattacharya later observed during his 2025 Senate confirmation hearing, such absolutism erodes trust.

“In public health, we need to make sure the products of science are ethically acceptable to everybody,” he said. “Having alternatives that are not ethically conflicted with foetal cell lines is not just an ethical issue — it’s a public health issue.”

Safety Assumed, Not Proven

When the discussion turned to safety, Siri asked, “Are you aware of any study that compares vaccinated children to completely unvaccinated children?”

Plotkin replied that he was “not aware of well-controlled studies.”

Asked why no placebo-controlled trials had been conducted on routine childhood vaccines such as hepatitis B, Plotkin said such trials would be “ethically difficult.”

That rationale, Siri noted, creates a scientific blind spot. If trials are deemed too unethical to conduct, then gold-standard safety data — the kind required for other pharmaceuticals — simply do not exist for the full childhood vaccine schedule.

Siri pointed to one example: Merck’s hepatitis B vaccine, administered to newborns. The company had only monitored participants for adverse events for five days after injection.

Plotkin didn’t dispute it. “Five days is certainly short for follow-up,” he admitted, but claimed that “most serious events” would occur within that time frame.

Siri challenged the idea that such a narrow window could capture meaningful safety data — especially when autoimmune or neurodevelopmental effects could take weeks or months to emerge.

Siri pushed on. He asked Plotkin if the DTaP and Tdap vaccines — for diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis — could cause autism.

“I feel confident they do not,” Plotkin replied.

But when shown the Institute of Medicine’s 2011 report, which found the evidence “inadequate to accept or reject” a causal link between DTaP and autism, Plotkin countered, “Yes, but the point is that there were no studies showing that it does cause autism.”

In that moment, Plotkin embraced a fallacy: treating the absence of evidence as evidence of absence.

“You’re making assumptions, Dr Plotkin,” Siri challenged. “It would be a bit premature to make the unequivocal, sweeping statement that vaccines do not cause autism, correct?”

Plotkin relented. “As a scientist, I would say that I do not have evidence one way or the other.”

The MMR

The deposition also exposed the fragile foundations of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine.

When Siri asked for evidence of randomised, placebo-controlled trials conducted before MMR’s licensing, Plotkin pushed back: “To say that it hasn’t been tested is absolute nonsense,” he said, claiming it had been studied “extensively.”

Pressed to cite a specific trial, Plotkin couldn’t name one. Instead, he gestured to his own 1,800-page textbook: “You can find them in this book, if you wish.”

Siri replied that he wanted an actual peer-reviewed study, not a reference to Plotkin’s own book. “So you’re not willing to provide them?” he asked. “You want us to just take your word for it?”

Plotkin became visibly frustrated.

Eventually, he conceded there wasn’t a single randomised, placebo-controlled trial. “I don’t remember there being a control group for the studies, I’m recalling,” he said.

The exchange foreshadowed a broader shift in public discourse, highlighting long-standing concerns that some combination vaccines were effectively grandfathered into the schedule without adequate safety testing.

In September this year, President Trump called for the MMR vaccine to be broken up into three separate injections.

The proposal echoed a view that Andrew Wakefield had voiced decades earlier — namely, that combining all three viruses into a single shot might pose greater risk than spacing them out.

Wakefield was vilified and struck from the medical register. But now, that same question — once branded as dangerous misinformation — is set to be re-examined by the CDC’s new vaccine advisory committee, chaired by Martin Kulldorff.

The Aluminium Adjuvant Blind Spot

Siri next turned to aluminium adjuvants — the immune-activating agents used in many childhood vaccines.

When asked whether studies had compared animals injected with aluminium to those given saline, Plotkin conceded that research on their safety was limited.

Siri pressed further, asking if aluminium injected into the body could travel to the brain. Plotkin replied, “I have not seen such studies, no, or not read such studies.”

When presented with a series of papers showing that aluminium can migrate to the brain, Plotkin admitted he had not studied the issue himself, acknowledging that there were experiments “suggesting that that is possible.”

Asked whether aluminium might disrupt neurological development in children, Plotkin stated, “I’m not aware that there is evidence that aluminum disrupts the developmental processes in susceptible children.”

Taken together, these exchanges revealed a striking gap in the evidence base.

Compounds such as aluminium hydroxide and aluminium phosphate have been injected into babies for decades, yet no rigorous studies have ever evaluated their neurotoxicity against an inert placebo.

This issue returned to the spotlight in September 2025, when President Trump pledged to remove aluminium from vaccines, and world-leading researcher Dr Christopher Exley renewed calls for its complete reassessment.

A Broken Safety Net

Siri then turned to the reliability of the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) — the primary mechanism for collecting reports of vaccine-related injuries in the United States.

Did Plotkin believe most adverse events were captured in this database?

“I think…probably most are reported,” he replied.

But Siri showed him a government-commissioned study by Harvard Pilgrim, which found that fewer than 1% of vaccine adverse events are reported to VAERS.

“Yes,” Plotkin said, backtracking. “I don’t really put much faith into the VAERS system…”

Yet this is the same database officials routinely cite to claim that “vaccines are safe.”

Ironically, Plotkin himself recently co-authored a provocative editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, conceding that vaccine safety monitoring remains grossly “inadequate.”

Experimenting on the Vulnerable

Perhaps the most chilling part of the deposition concerned Plotkin’s history of human experimentation.

“Have you ever used orphans to study an experimental vaccine?” Siri asked.

“Yes,” Plotkin replied.

“Have you ever used the mentally handicapped to study an experimental vaccine?” Siri asked.

“I don’t recollect…I wouldn’t deny that I may have done so,” Plotkin replied.

Siri cited a study conducted by Plotkin in which he had administered experimental rubella vaccines to institutionalised children who were “mentally retarded.”

Plotkin stated flippantly, “Okay well, in that case…that’s what I did.”

There was no apology, no sign of ethical reflection — just matter-of-fact acceptance.

Siri wasn’t done.

He asked if Plotkin had argued that it was better to test on those “who are human in form but not in social potential” rather than on healthy children.

Plotkin admitted to writing it.

Siri established that Plotkin had also conducted vaccine research on the babies of imprisoned mothers, and on colonised African populations.

Plotkin appeared to suggest that the scientific value of such studies outweighed the ethical lapses—an attitude that many would interpret as the classic ‘ends justify the means’ rationale.

But that logic fails the most basic test of informed consent. Siri asked whether consent had been obtained in these cases.

“I don’t remember…but I assume it was,” Plotkin said.

Assume?

This was post-Nuremberg research. And the leading vaccine developer in America couldn’t say for sure whether he had properly informed the people he experimented on.

In any other field of medicine, such lapses would be disqualifying.

A Casual Dismissal of Parental Rights

Plotkin’s indifference to experimenting on disabled children didn’t stop there.

Siri asked whether someone who declined a vaccine due to concerns about missing safety data should be labelled “anti-vax.”

Plotkin replied, “If they refused to be vaccinated themselves or refused to have their children vaccinated, I would call them an anti-vaccination person, yes.”

Plotkin was less concerned about adults making that choice for themselves, but he had no tolerance for parents making those choices for their own children.

“The situation for children is quite different,” said Plotkin, “because one is making a decision for somebody else and also making a decision that has important implications for public health.”

In Plotkin’s view, the state held greater authority than parents over a child’s medical decisions — even when the science was uncertain.

The Enabling of Figures Like Plotkin

The Plotkin deposition stands as a case study in how conflicts of interest, ideology, and deference to authority have corroded the scientific foundations of public health.

Plotkin is no fringe figure. He is celebrated, honoured, and revered. Yet he promotes vaccines that have never undergone true placebo-controlled testing, shrugs off the failures of post-market surveillance, and admits to experimenting on vulnerable populations.

This is not conjecture or conspiracy — it is sworn testimony from the man who helped build the modern vaccine program.

Now, as Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. reopens long-dismissed questions about aluminium adjuvants and the absence of long-term safety studies, Plotkin’s once-untouchable legacy is beginning to fray.

Republished from the author’s Substack

Brownstone Institute

Bizarre Decisions about Nicotine Pouches Lead to the Wrong Products on Shelves

From the Brownstone Institute

A walk through a dozen convenience stores in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, says a lot about how US nicotine policy actually works. Only about one in eight nicotine-pouch products for sale is legal. The rest are unauthorized—but they’re not all the same. Some are brightly branded, with uncertain ingredients, not approved by any Western regulator, and clearly aimed at impulse buyers. Others—like Sweden’s NOAT—are the opposite: muted, well-made, adult-oriented, and already approved for sale in Europe.

Yet in the United States, NOAT has been told to stop selling. In September 2025, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued the company a warning letter for offering nicotine pouches without marketing authorization. That might make sense if the products were dangerous, but they appear to be among the safest on the market: mild flavors, low nicotine levels, and recyclable paper packaging. In Europe, regulators consider them acceptable. In America, they’re banned. The decision looks, at best, strange—and possibly arbitrary.

What the Market Shows

My October 2025 audit was straightforward. I visited twelve stores and recorded every distinct pouch product visible for sale at the counter. If the item matched one of the twenty ZYN products that the FDA authorized in January, it was counted as legal. Everything else was counted as illegal.

Two of the stores told me they had recently received FDA letters and had already removed most illegal stock. The other ten stores were still dominated by unauthorized products—more than 93 percent of what was on display. Across all twelve locations, about 12 percent of products were legal ZYN, and about 88 percent were not.

The illegal share wasn’t uniform. Many of the unauthorized products were clearly high-nicotine imports with flashy names like Loop, Velo, and Zimo. These products may be fine, but some are probably high in contaminants, and a few often with very high nicotine levels. Others were subdued, plainly meant for adult users. NOAT was a good example of that second group: simple packaging, oat-based filler, restrained flavoring, and branding that makes no effort to look “cool.” It’s the kind of product any regulator serious about harm reduction would welcome.

Enforcement Works

To the FDA’s credit, enforcement does make a difference. The two stores that received official letters quickly pulled their illegal stock. That mirrors the agency’s broader efforts this year: new import alerts to detain unauthorized tobacco products at the border (see also Import Alert 98-06), and hundreds of warning letters to retailers, importers, and distributors.

But effective enforcement can’t solve a supply problem. The list of legal nicotine-pouch products is still extremely short—only a narrow range of ZYN items. Adults who want more variety, or stores that want to meet that demand, inevitably turn to gray-market suppliers. The more limited the legal catalog, the more the illegal market thrives.

Why the NOAT Decision Appears Bizarre

The FDA’s own actions make the situation hard to explain. In January 2025, it authorized twenty ZYN products after finding that they contained far fewer harmful chemicals than cigarettes and could help adult smokers switch. That was progress. But nine months later, the FDA has approved nothing else—while sending a warning letter to NOAT, arguably the least youth-oriented pouch line in the world.

The outcome is bad for legal sellers and public health. ZYN is legal; a handful of clearly risky, high-nicotine imports continue to circulate; and a mild, adult-market brand that meets European safety and labeling rules is banned. Officially, NOAT’s problem is procedural—it lacks a marketing order. But in practical terms, the FDA is punishing the very design choices it claims to value: simplicity, low appeal to minors, and clean ingredients.

This approach also ignores the differences in actual risk. Studies consistently show that nicotine pouches have far fewer toxins than cigarettes and far less variability than many vapes. The biggest pouch concerns are uneven nicotine levels and occasional traces of tobacco-specific nitrosamines, depending on manufacturing quality. The serious contamination issues—heavy metals and inconsistent dosage—belong mostly to disposable vapes, particularly the flood of unregulated imports from China. Treating all “unauthorized” products as equally bad blurs those distinctions and undermines proportional enforcement.

A Better Balance: Enforce Upstream, Widen the Legal Path

My small Montgomery County survey suggests a simple formula for improvement.

First, keep enforcement targeted and focused on suppliers, not just clerks. Warning letters clearly change behavior at the store level, but the biggest impact will come from auditing distributors and importers, and stopping bad shipments before they reach retail shelves.

Second, make compliance easy. A single-page list of authorized nicotine-pouch products—currently the twenty approved ZYN items—should be posted in every store and attached to distributor invoices. Point-of-sale systems can block barcodes for anything not on the list, and retailers could affirm, once a year, that they stock only approved items.

Third, widen the legal lane. The FDA launched a pilot program in September 2025 to speed review of new pouch applications. That program should spell out exactly what evidence is needed—chemical data, toxicology, nicotine release rates, and behavioral studies—and make timely decisions. If products like NOAT meet those standards, they should be authorized quickly. Legal competition among adult-oriented brands will crowd out the sketchy imports far faster than enforcement alone.

The Bottom Line

Enforcement matters, and the data show it works—where it happens. But the legal market is too narrow to protect consumers or encourage innovation. The current regime leaves a few ZYN products as lonely legal islands in a sea of gray-market pouches that range from sensible to reckless.

The FDA’s treatment of NOAT stands out as a case study in inconsistency: a quiet, adult-focused brand approved in Europe yet effectively banned in the US, while flashier and riskier options continue to slip through. That’s not a public-health victory; it’s a missed opportunity.

If the goal is to help adult smokers move to lower-risk products while keeping youth use low, the path forward is clear: enforce smartly, make compliance easy, and give good products a fair shot. Right now, we’re doing the first part well—but failing at the second and third. It’s time to fix that.

-

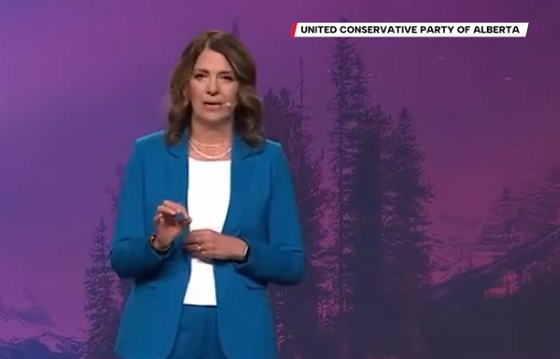

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoThis new Canada–Alberta pipeline agreement will cost you more than you think

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoUnceded is uncertain

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days agoPower Struggle: Governments start quietly backing away from EV mandates

-

Business17 hours ago

Business17 hours agoCanada’s climate agenda hit business hard but barely cut emissions

-

Energy22 hours ago

Energy22 hours agoCanada following Europe’s stumble by ignoring energy reality

-

MAiD1 day ago

MAiD1 day agoFrom Exception to Routine. Why Canada’s State-Assisted Suicide Regime Demands a Human-Rights Review

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta will defend law-abiding gun owners who defend themselves

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney government should privatize airports—then open airline industry to competition