Aristotle Foundation

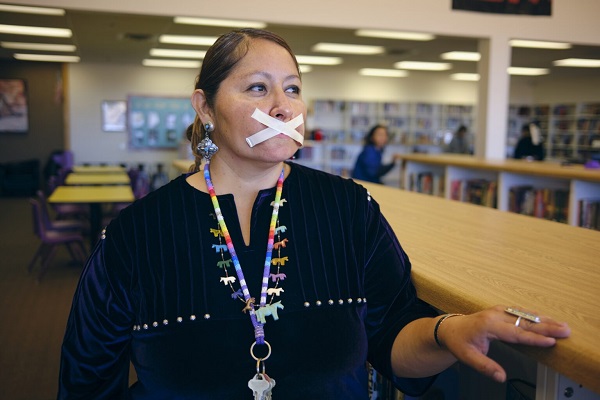

Criminalizing residential school ‘denialism’ would silence indigenous voices, too

By Mark Milke

The effort by MP Leah Gazan to criminalize residential school views she labels “denialist” is a mistake. Gazan’s Bill C-413, if passed, would criminalize any statement that might be interpreted as “condoning, denying, downplaying or justifying the Indian residential school system in Canada through statements communicated other than in private conversation.”

Let’s start with examples of whose speech Gazan’s bill would criminalize, if repeated in the future: indigenous Canadians who have publicly “condoned,” or at least partly justified, residential schools.

In 1998, Rita Galloway, a teacher who grew up on the Pelican Lake First Nation in Saskatchewan and then-president of the First Nations Accountability Coalition, was interviewed about residential schools. She noted that she had “many friends and relatives who attended residential schools,” and argued, “Of course there were good and bad elements, but overall, their experiences were positive.”

In 2008, the late Richard Wagamese, an Ojibwe author and journalist, wrote in the Calgary Herald about the many abuses that took place at residential schools. He then straightforwardly argued that positive stories needed to be told, too, including his mother’s.

After praising her neat, clean home and cultured lawn on a reserve outside Kenora, Ont., Wagamese noted how his 75-year-old mother “credits the residential school experience with teaching her domestic skills.” Critically, “My mother has never spoken to me of abuse or any catastrophic experience at the school.”

Wagamese argued the then-forthcoming Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) “needs to hear those kinds of stories, too,” and that telling “the good along with the bad” will “create a more balanced future for all of us.”

That’s not because such schools were perfect — or even optimal. As has been extensively documented, physical and sexual abuses occurred in some schools, and that is something that no one should downplay.

But it’s too easy to forget the limited choices that existed for 19th- and early 20th-century Canadians. As we do today, most people back then believed in the value of universal education. Many Canadians, indigenous and non-indigenous, lived in poverty, had rudimentary transportation links, limited job opportunities and thus limited possibilities for day schools in remote areas, such as reserves.

Imagine the outcry today if earlier generations of parishioners, parents (including Indigenous parents) and politicians mostly ignored remote reserves and failed to provide indigenous communities with educational opportunities. The same voices today who accept no nuance on residential schools would likely excoriate that choice to deny education to Indigenous children.

The choices in the 19th and 20th centuries were not between perfection and its opposite; they represent a trade-off between suboptimal choices. Understanding this requires nuance, which is in short supply these days.

As an example, consider the perspective of Manitoba school trustee Paul Coffey, a Metis man who made a presentation to the Mountain View School Division board meeting in Dauphin, Man., about racism in April and was pilloried for it. His remarks included comments about residential schools. Coffey tried to argue that residential schools had good and bad aspects, but he was roundly criticized for his views.

In a July interview, Coffey again offered nuance about the schools, noting what much of the media missed in their initial firestorm coverage: “I said they were nice. I then also said they weren’t. I said treaties were nice and then they weren’t. I said even TRC is a good idea, until it isn’t.”

Criminalizing these stories and opinions would mean that these three indigenous voices, and many others, could face fines or jail time. This is precisely why speech, unless urging violence, should never be criminalized.

Another reason not to criminalize speech is because it makes it even more difficult to correct bad ideas and lingering injustices. An open society requires open discourse. It’s the only way errors can only be corrected. That disappears if one becomes subject to fines and imprisonment for thinking out loud, including when one is ultimately proved to be in error.

Gazan’s bill is the latest attempt by Canadian politicians to suppress views and conclusions with which they disagree. That suppression is illiberal and unhelpful. Mandating a single point of view damages the accumulation of knowledge that’s necessary for progress, prevents a useful dissection of why abuses occurred in residential schools and will prevent the open discrediting of wrongheaded positions.

No one person will be right every time. Open, public debate is critical to exposing errors and advancing human progress.

Mark Milke is the president of the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy.

Aristotle Foundation

How Vimy Ridge Shaped Canada

The Battle of Vimy Ridge was a unifying moment for Canada, then a young country. The Aristotle Foundation’s Danny Randell explains what happened at Vimy in 1917, and why it still matters to Canada today.

About the Aristotle Foundation

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a new think tank that aims to renew civil, common-sense discourse in Canada. As an educational charity, we publish books, videos, fact sheets, studies, columns, interviews, and infographics.

Visit our website at www.aristotlefoundation.org for more of our content.

Aristotle Foundation

The Canadian Medical Association’s inexplicable stance on pediatric gender medicine

By Dr. J. Edward Les

The thalidomide saga is particularly instructive: Canada was the last developed country to pull thalidomide from its shelves — three months during which babies continued to be born in this country with absent or deformed limbs

Physicians have a duty to put forward the best possible evidence, not ideology, based treatments

Late last month, the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) announced that it, along with three Alberta doctors, had filed a constitutional challenge to Alberta’s Bill 26 “to protect the relationship between patients, their families and doctors when it comes to making treatment decisions.”

Bill 26, which became law last December, prohibits doctors in the province from prescribing puberty blockers and hormone therapies for those under 16; it also bans doctors from performing gender-reassignment surgeries on minors (those under 18).

The unprecedented CMA action follows its strongly worded response in February 2024 to Alberta’s (at the time) proposed legislation:

“The CMA is deeply concerned about any government proposal that restricts access to evidence-based medical care, including the Alberta government’s proposed restrictions on gender-affirming treatments for pediatric transgender patients.”

But here’s the problem with that statement, and with the CMA’s position: the evidence supporting the “gender affirmation” model of care — which propels minors onto puberty blockers, cross-gender hormones, and in some cases, surgery — is essentially non-existent. That’s why the United Kingdom’s Conservative government, in the aftermath of the exhaustive four-year-long Cass Review, which laid bare the lack of evidence for that model, and which shone a light on the deeply troubling potential for the model’s irreversible harm to youth, initiated a temporary ban on puberty blockers — a ban made permanent last December by the subsequent Labour government. And that’s why other European jurisdictions like Finland and Sweden, after reviews of gender affirming care practices in their countries, have similarly slammed the brakes on the administration of puberty blockers and cross-gender hormones to minors.

It’s not only the Europeans who have raised concerns. The alarm bells are ringing loudly within our own borders: earlier this year, a group at McMaster University, headed by none other than Dr. Gordon Guyatt, one of the founding gurus of the “evidence-based care” construct that rightfully underpins modern medical practice, issued a pair of exhaustive systematic reviews and meta analyses that cast grave doubts on the wisdom of prescribing these drugs to youth.

And yet, the CMA purports to be “deeply concerned about any government proposal that restricts access to evidence-based medical care,” which begs the obvious question: Where, exactly, is the evidence for the benefits of the “gender affirming” model of care? The answer is that it’s scant at best. Worse, the evidence that does exist, points, on balance, to infliction of harm, rather than provision of benefit.

CMA President Joss Reimer, in the group’s announcement of the organization’s legal action, said:

“Medicine is a calling. Doctors pursue it because they are compelled to care for and promote the well-being of patients. When a government bans specific treatments, it interferes with a doctor’s ability to empower patients to choose the best care possible.”

Indeed, we physicians have a sacred duty to pursue the well-being of our patients. But that means that we should be putting forward the best possible treatments based on actual evidence.

When Dr. Reimer states that a government that bans specific treatments is interfering with medical care, she displays a woeful ignorance of medical history. Because doctors don’t always get things right: look to the sad narratives of frontal lobotomies, the oxycontin crisis, thalidomide, to name a few.

The thalidomide saga is particularly instructive: it illustrates what happens when a government drags its heels on necessary action. Canada was the last developed country to pull thalidomide, given to pregnant women for morning sickness, from its shelves, three months after it had been banned everywhere else — three months during which babies continued to be born in this country with absent or deformed limbs, along with other severe anomalies. It’s a shameful chapter in our medical past, but it pales in comparison to the astonishing intransigence our medical leaders have displayed — and continue to display — on the youth gender care file.

A final note (prompted by thalidomide’s history), to speak to a significant quibble I have with Alberta’s Bill 26 legislation: as much as I admire Premier Danielle Smith’s courage in bringing it forward, the law contains a loophole allowing minors already on puberty blockers and cross-gender hormones to continue to take them. Imagine if, after it was removed from the shelves in 1962, government had allowed pregnant women already on the drug to continue to take thalidomide. Would that have made any sense? Of course not. And the same applies to puberty blockers and cross-gender hormones: they should be banned outright for all youth.

That argument is the kind our medical associations should be making — and would be making, if they weren’t so firmly in the grasp, seemingly, of ideologues who have abandoned evidence-based medical care for our youth.

J. Edward Les is a Calgary pediatrician, a senior fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy, and co-author of “Teenagers, Children, and Gender Transition Policy: A Comparison of Transgender Medical Policy for Minors in Canada, the United States, and Europe.”

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoRFK Jr. says Hep B vaccine is linked to 1,135% higher autism rate

-

Crime2 days ago

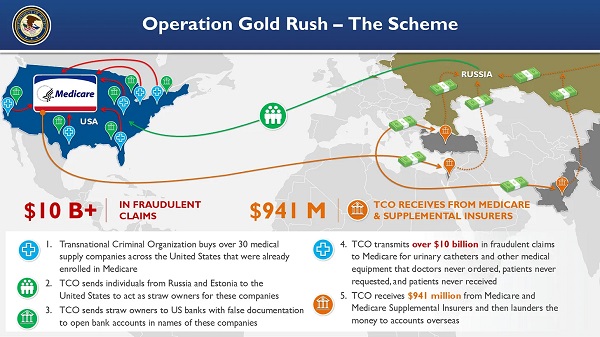

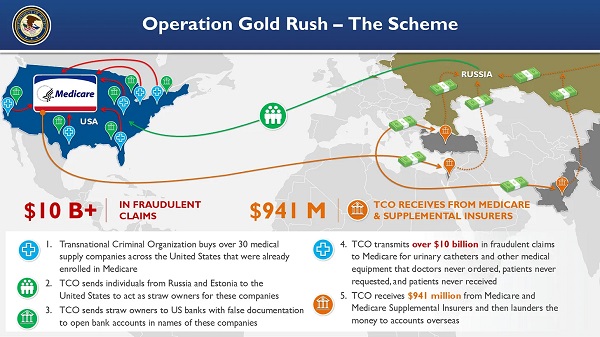

Crime2 days agoNational Health Care Fraud Takedown Results in 324 Defendants Charged in Connection with Over $14.6 Billion in Alleged Fraud

-

Business14 hours ago

Business14 hours agoWhy it’s time to repeal the oil tanker ban on B.C.’s north coast

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoGlobal media alliance colluded with foreign nations to crush free speech in America: House report

-

Alberta9 hours ago

Alberta9 hours agoAlberta Provincial Police – New chief of Independent Agency Police Service

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoRFK Jr. Unloads Disturbing Vaccine Secrets on Tucker—And Surprises Everyone on Trump

-

Alberta14 hours ago

Alberta14 hours agoPierre Poilievre – Per Capita, Hardisty, Alberta Is the Most Important Little Town In Canada

-

Opinion6 hours ago

Opinion6 hours agoBlind to the Left: Canada’s Counter-Extremism Failure Leaves Neo-Marxist and Islamist Threats Unchecked