Business

Costly construction isn’t the culprit behind unaffordable housing

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Wendell Cox

Land restriction creates what amount to land cartels. A now smaller number of landowners gain windfall profits, which, of course, encourages speculation

The latest Demographia report on housing affordability in Canada, which I produce for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy, reveals that over half of the 46 Canadian housing markets we assess are severely unaffordable. In fact, Vancouver and Toronto rank as third and 10th least affordable, respectively, among the 94 major global markets included in our latest international housing affordability study.

To evaluate housing costs, we utilize the “median multiple,” which divides the median house price within a given market (census metropolitan area) by its median household income. A multiple equal to or less than 3.0 is categorized as “affordable,” while anything exceeding 5.0 is labelled “severely unaffordable.”

Among the major Canadian housing markets, Vancouver (with a median multiple of 12), Toronto (9.5), Montreal (5.4), and Ottawa-Gatineau (5.2) fall into the severely unaffordable category. Vancouver has maintained a high median multiple for several decades, while Toronto has been in this range for approximately two decades. The increased prevalence of telecommuting has recently contributed to Montreal and Ottawa-Gatineau’s affordability challenges, leading to a surge in demand for larger homes and properties in more distant suburbs. In contrast, housing in Edmonton (4.0) and Calgary (4.3) remains comparatively affordable.

In Toronto and Vancouver, the implementation of international urban planning principles, particularly those promoting anti-sprawl measures like greenbelts and agricultural preserves, has led to unprecedented price hikes. This “urban containment” approach has consistently driven up land values where it has been adopted. And high land values rather than increased construction costs are what explain the substantial disparity between severely unaffordable and more budget-friendly markets.

Land restriction creates what amount to land cartels. A now smaller number of landowners gain windfall profits, which, of course, encourages speculation. Maintaining or restoring affordability requires eliminating windfall profits by ensuring a competitive market for land.

Another issue arises from urban planners’ preference for higher-density housing, such as high-rise condos. Some households may prefer high-rise living, but families with children typically seek housing with more land, whether detached or semi-detached. When they’re priced out of good housing markets, their quality of life suffers and they may even fall into poverty.

The troubling paradox is that unaffordable housing is far more common in markets like Vancouver and Toronto, which have embraced the planning orthodoxy — which is supposed to produce affordable housing. The same applies to international markets like Sydney, Auckland, London and San Francisco, where urban containment and unaffordable housing have gone hand in hand.

What’s the solution? Give up on urban containment and make more land available for housing. But wouldn’t that threaten the natural environment, as critics of Ontario’s recent attempt to allow development of a sliver of its greenbelt argued?

Not at all. It’s true that land under cultivation in Canada has been declining steadily over the years. But the culprit is improved agricultural productivity, not urban expansion. According to Statistics Canada, between 2001 and 2021, agricultural land shrank 53,000 square kilometres. That’s about equal to the land area of Nova Scotia. And it’s about triple all the area urbanized since European settlement began. Even in Ontario and B.C. where most of the severely unaffordable markets are concentrated, urban expansion from 2016 to 2021 took up less than one-quarter of the agricultural loss over that period. Urban expansion is not squeezing out agricultural land.

Given all this, what should we do about affordability? In my view, three things:

First, it’s essential to acknowledge that Canadians are already addressing the issue by relocating from pricier to more affordable regions. Housing is more affordable in the Atlantic and Prairie provinces and areas in Quebec east of Montreal. So it’s not surprising there is now a net influx of people to smaller, typically more affordable, locations. In the past five years, markets with populations exceeding 100,000 have collectively witnessed over 250,000 people moving to smaller markets.

Second, make more land available for development in increasingly unaffordable markets like B.C., southern Ontario, and the Montreal-Ottawa corridor. One way is with “housing opportunity enclaves” (HOEs), in which traditional, i.e., not high-density, housing regulations would apply, but essential environmental and safety regulations would. The aim would be to provide middle-income housing at the price-to-income ratios that were typical before urban containment came along and housing across the country was largely affordable.

Market-driven development would be ensured by relying on the private sector to provide housing, land, and infrastructure, a model that has been successful in Colorado and Texas. Current residents would maintain their property rights but could sell to private parties and First Nations for development.

HOEs would be situated far enough outside major centres to take advantage of low-priced land, prioritizing areas with the largest recent agricultural land reductions. Communities likely would resemble Waverly West in Winnipeg or The Woodlands in Houston, with ample housing space and yards for families with children.

These new communities would attract people working at least partly from home. Jobs would naturally follow, creating self-contained communities where most commutes occurred within the HOE. To ensure a competitive market and prevent land cost escalation, HOEs must have ample land available.

Third, public authorities should allocate an ample amount of suburban land to safeguard reasonable land values in the Prairie and Atlantic provinces, as well as in Quebec east of Montreal. This would allow currently more affordable markets such as Quebec City, Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Moncton and Halifax to accommodate interprovincial migrants without jeopardizing their affordability.

Provincial and local governments would need to monitor housing affordability multiples on at least a five-year cycle, and legislatures, land use authorities and city councils would have to allow enough low-cost land development to maintain price-to-income stability.

It’s not enough just to provide enough building lots to meet projected demand. The goal should be to enable builders to provide housing at prices middle-income households can afford. The key to that is affordable land.

Wendell Cox is a Senior Fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. He is the author of 2023 Edition Of Demographia Housing Affordability In Canada and has been featured on Leaders on the Frontier – Cost of Living Under Crisis With Charles Blain.

Business

Mark Carney’s Fiscal Fantasy Will Bankrupt Canada

By Gwyn Morgan

Mark Carney was supposed to be the adult in the room. After nearly a decade of runaway spending under Justin Trudeau, the former central banker was presented to Canadians as a steady hand – someone who could responsibly manage the economy and restore fiscal discipline.

Instead, Carney has taken Trudeau’s recklessness and dialled it up. His government’s recently released spending plan shows an increase of 8.5 percent this fiscal year to $437.8 billion. Add in “non-budgetary spending” such as EI payouts, plus at least $49 billion just to service the burgeoning national debt and total spending in Carney’s first year in office will hit $554.5 billion.

Even if tax revenues were to remain level with last year – and they almost certainly won’t given the tariff wars ravaging Canadian industry – we are hurtling toward a deficit that could easily exceed 3 percent of GDP, and thus dwarf our meagre annual economic growth. It will only get worse. The Parliamentary Budget Officer estimates debt interest alone will consume $70 billion annually by 2029. Fitch Ratings recently warned of Canada’s “rapid and steep fiscal deterioration”, noting that if the Liberal program is implemented total federal, provincial and local debt would rise to 90 percent of GDP.

This was already a fiscal powder keg. But then Carney casually tossed in a lit match. At June’s NATO summit, he pledged to raise defence spending to 2 percent of GDP this fiscal year – to roughly $62 billion. Days later, he stunned even his own caucus by promising to match NATO’s new 5 percent target. If he and his Liberal colleagues follow through, Canada’s defence spending will balloon to the current annual equivalent of $155 billion per year. There is no plan to pay for this. It will all go on the national credit card.

This is not “responsible government.” It is economic madness.

And it’s happening amid broader economic decline. Business investment per worker – a key driver of productivity and living standards – has been shrinking since 2015. The C.D. Howe Institute warns that Canadian workers are increasingly “underequipped compared to their peers abroad,” making us less competitive and less prosperous.

The problem isn’t a lack of money; it’s a lack of discipline and vision. We’ve created a business climate that punishes investment: high taxes, sluggish regulatory processes, and politically motivated uncertainty. Carney has done nothing to reverse this. If anything, he’s making the situation worse.

Recall the 2008 global financial meltdown. Carney loves to highlight his role as Bank of Canada Governor during that time but the true credit for steering the country through the crisis belongs to then-prime minister Stephen Harper and his finance minister, Jim Flaherty. Facing the pressures of a minority Parliament, they made the tough decisions that safeguarded Canada’s fiscal foundation. Their disciplined governance is something Carney would do well to emulate.

Instead, he’s tearing down that legacy. His recent $4.3 billion aid pledge to Ukraine, made without parliamentary approval, exemplifies his careless approach. And his self-proclaimed image as the experienced technocrat who could go eyeball-to-eyeball against Trump is starting to crack. Instead of respecting Carney, Trump is almost toying with him, announcing in June, for example that the U.S. would pull out of the much-ballyhooed bilateral trade talks launched at the G7 Summit less than two weeks earlier.

Ordinary Canadians will foot the bill for Carney’s fiscal mess. The dollar has weakened. Young Canadians – already priced out of the housing market – will inherit a mountain of debt. This is not stewardship. It’s generational theft.

Some still believe Carney will pivot – that he will eventually govern sensibly. But nothing in his actions supports that hope. A leader serious about economic renewal would cancel wasteful Trudeau-era programs, streamline approvals for energy and resource projects, and offer incentives for capital investment. Instead, we’re getting more borrowing and ideological showmanship.

It’s no longer credible to say Carney is better than Trudeau. He’s worse. Trudeau at least pretended deficits were temporary. Carney has made them permanent – and more dangerous.

This is a betrayal of the fiscal stability Canadians were promised. If we care about our credit rating, our standard of living, or the future we are leaving our children, we must change course.

That begins by removing a government unwilling – or unable – to do the job.

Canada once set an economic example for others. Those days are gone. The warning signs – soaring debt, declining productivity, and diminished global standing – are everywhere. Carney’s defenders may still hope he can grow into the job. Canada cannot afford to wait and find out.

The original, full-length version of this article was recently published in C2C Journal.

Gwyn Morgan is a retired business leader who was a director of five global corporations.

Business

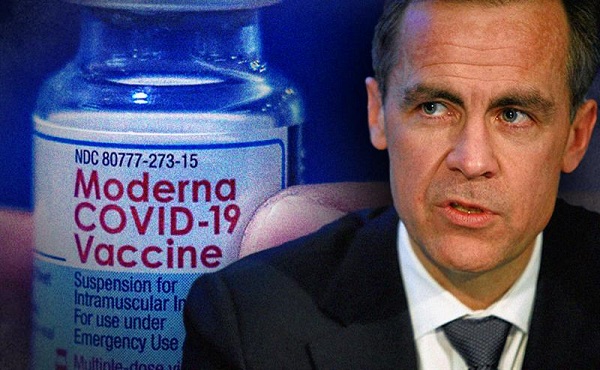

Carney Liberals quietly award Pfizer, Moderna nearly $400 million for new COVID shot contracts

From LifeSiteNews

Carney’s Liberal government signed nearly $400 million in contracts with Pfizer and Moderna for COVID shots, despite halted booster programs and ongoing delays in compensating Canadians for jab injuries.

Prime Minister Mark Carney has awarded Pfizer and Moderna nearly $400 million in new COVID shot contracts.

On June 30th, the Liberal government quietly signed nearly $400 million contracts with vaccine companies Pfizer and Moderna for COVID jabs, despite thousands of Canadians waiting to receive compensation for COVID shot injuries.

The contracts, published on the Government of Canada website, run from June 30, 2025, until March 31, 2026. Under the contracts, taxpayers must pay $199,907,418.00 to both companies for their COVID shots.

Notably, there have been no press releases regarding the contracts on the Government of Canada website nor from Carney’s official office.

Additionally, the contracts were signed after most Canadians provinces halted their COVID booster shot programs. At the same time, many Canadians are still waiting to receive compensation from COVID shot injuries.

Canada’s Vaccine Injury Support Program (VISP) was launched in December 2020 after the Canadian government gave vaccine makers a shield from liability regarding COVID-19 jab-related injuries.

There has been a total of 3,317 claims received, of which only 234 have received payments. In December, the Canadian Department of Health warned that COVID shot injury payouts will exceed the $75 million budget.

The December memo is the last public update that Canadians have received regarding the cost of the program. However, private investigations have revealed that much of the funding is going in the pockets of administrators, not injured Canadians.

A July report by Global News discovered that Oxaro Inc., the consulting company overseeing the VISP, has received $50.6 million. Of that fund, $33.7 million has been spent on administrative costs, compared to only $16.9 million going to vaccine injured Canadians.

Furthermore, the claims do not represent the total number of Canadians injured by the allegedly “safe and effective” COVID shots, as inside memos have revealed that the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) officials neglected to report all adverse effects from COVID jabs and even went as far as telling staff not to report all events.

The PHAC’s downplaying of jab injuries is of little surprise to Canadians, as a 2023 secret memo revealed that the federal government purposefully hid adverse effect so as not to alarm Canadians.

The secret memo from former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Privy Council Office noted that COVID jab injuries and even deaths “have the potential to shake public confidence.”

“Adverse effects following immunization, news reports and the government’s response to them have the potential to shake public confidence in the COVID-19 vaccination rollout,” read a part of the memo titled “Testing Behaviourally Informed Messaging in Response to Severe Adverse Events Following Immunization.”

Instead of alerting the public, the secret memo suggested developing “winning communication strategies” to ensure the public did not lose confidence in the experimental injections.

Since the start of the COVID crisis, official data shows that the virus has been listed as the cause of death for less than 20 children in Canada under age 15. This is out of six million children in the age group.

The COVID jabs approved in Canada have also been associated with severe side effects, such as blood clots, rashes, miscarriages, and even heart attacks in young, healthy men.

Additionally, a recent study done by researchers with Canada-based Correlation Research in the Public Interest showed that 17 countries have found a “definite causal link” between peaks in all-cause mortality and the fast rollouts of the COVID shots, as well as boosters.

Interestingly, while the Department of Health has spent $16 million on injury payouts, the Liberal government spent $54 million COVID propaganda promoting the shot to young Canadians.

The Public Health Agency of Canada especially targeted young Canadians ages 18-24 because they “may play down the seriousness of the situation.”

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney government should apply lessons from 1990s in spending review

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoTrump to impose 30% tariff on EU, Mexico

-

illegal immigration2 days ago

illegal immigration2 days agoICE raids California pot farm, uncovers illegal aliens and child labor

-

Entertainment1 day ago

Entertainment1 day agoStudy finds 99% of late-night TV guests in 2025 have been liberal

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoLNG Export Marks Beginning Of Canadian Energy Independence

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy13 hours ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy13 hours agoCanada’s New Border Bill Spies On You, Not The Bad Guys

-

Uncategorized13 hours ago

Uncategorized13 hours agoCNN’s Shock Climate Polling Data Reinforces Trump’s Energy Agenda

-

Opinion6 hours ago

Opinion6 hours agoPreston Manning: Three Wise Men from the East, Again