Business

Chainsaws and Scalpels: How Governments Choose

Javier Milei in Argentina, Musk and Ramaswamy in the US.. What does DOGE in Canada look like?

Under their new(ish) president Javier Milei, Argentina cut deeply and painfully into their program spending to address a catastrophic economic crisis. And they seem to have enjoyed some early success. With Elon Musk now primed to play a similar role in the coming Trump administration in the U.S., the obvious question is: how might such an approach play out in Canada?

Sure. We’re not suffering from headaches on anything like the scale of Argentina’s – the debt we’ve run up so far isn’t in the same league as the long-term spending going on in South America. But ignoring the problems we do face can’t be an option. Given that the annual interest payments on our existing national debt are $11.7 billion (which equals seven percent of total expenditures), simply balancing the budget won’t be enough.

The underlying assumption powering the question is that we live in a world of constraints. There just isn’t enough money to buy everything we might want, so we need to both prioritize and become more efficient. It’s about figuring out what can no longer be justified – even if it does provide some value – and what’s just plain wasteful.

The Audit is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Some of this may seem obvious. After all, when there are First Nations reserves without clean water and millions of Canadians without access to primary care physicians, how can we justify spending hundreds of millions of dollars funding arts projects that virtually no one will ever discover, much less consume?

Apparently not everyone sees things that way. Large governments operate by reacting to political, social, and chaos-driven incentives. Sometimes those incentives lead to rational choices, and sometimes not. But mega-sized organizations tend to lack the self-awareness and capacity to easily change direction.

And some basic problems have no obvious solutions. As I’ve written, there’s a real possibility that all the money in the world won’t buy the doctors, nurses, and integrated systems we need. And “all the money in the world” is obviously not on the table. So the well-meaning bureaucrat might conclude that if you’re not going to completely solve the big problems, you might as well try to manage them while investing in other areas, too.

Still, I think it’s worth imagining how things might look if we could launch a comprehensive whole-of-government program review.

How Emergency Cuts Might Play Out

Imagine the federal government defaulted on its debt servicing payments and lost access to capital markets. That’s not such an unlikely scenario. There would suddenly be a lot less money available to spend, and some programs would have to be shut down. Protecting emergency and core services would require making fast – and smart – decisions.

We would need to take a long, hard look at this important enumeration of government expenditures. There probably wouldn’t be enough time to bridge the gap by looking for dozens of less-critical million-dollar programs. We would need to find some big-ticket items fast.

Our first step might be to pause or restructure larger ongoing payments, like projects funded through the Canada Infrastructure Bank (total annual budget: $3.45 billion). Private investors might pick up some of the slack, or some projects could simply go into hibernation. “Other interest costs” (total annual budget: $4.6 billion) could also be restructured.

Reducing equalization payments (total annual budget: $25.2 billion) and territorial financing (total budget: $5.2 billion) might also be necessary. This would, of course, spark parallel crises at lower levels of government. Similarly, grants to settle First Nations claims (total budget: $6 billion) managed by Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada would also be at least temporarily cut.

All that would be deeply painful and trigger long-term negative consequences.

But there’s a far better approach that could be just as effective and a whole lot less painful:

What an All-of-Government Review Might Discover

Planning ahead would allow you the luxury of targeting spending that – in some cases at least – wouldn’t even be missed. Think about programs that were announced five, ten, even thirty years ago, perhaps to satisfy some passing fad or political need. They might even have made sense decades ago when they were created…but that was decades ago when they were created.

Here’s how that’ll work. When you read through the program and transfer spending items on that government expenditures page (and there are around 1,200 of those items), the descriptions all point to goals that seem reasonable enough. But there are some important questions that should be asked about each of them:

- When did these programs begin?

- What specific activities do they involve?

- What have they accomplished over the past 12 months?

- Is their effectiveness trending up or down?

- Are they employing efficiency best-practices used in the private sector?

- Who’s tasked with monitoring changes?

- Where are their reports published?

To show you what I mean, here are some specific transfer or program line items and their descriptions:

Department of Employment and Social Development

- Workforce Development Agreements ($722 million)

- Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care Transformation Initiative ($374 million)

- Payments to provinces, territories, municipalities, other public bodies, organizations, groups, communities, employers and individuals for the provision of training and/or work experience, the mobilization of community resources, and human resource planning and adjustment measures necessary for the efficient functioning of the Canadian labour market ($856 million)

Department of Industry

- Contributions under the Strategic Innovation Fund ($2.4 billion)

Department of Citizenship and Immigration

- Settlement Program ($1.13 billion)

Department of Indigenous Services

- Contributions to provide income support to on-reserve residents and Status Indians in the Yukon Territory ($1.05 billion). Note that, as of the 2021 Census, there were 9,150 individuals with North American Indigenous origins in Yukon. Assuming the line item is accurately described, that means the income support came to $114,987/person (not per household; per person).

Each one of those (and many, many others like them) could be case studies in operational efficiency and effectiveness. Or not. But there’s no way we could know that without serious research.

The Audit is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

Business

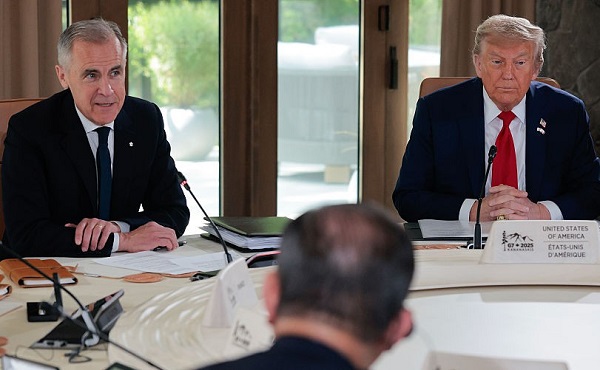

Trump makes impact on G7 before he makes his exit

Trump Rips Into Obama and Trudeau at G7 for a “Very Big Mistake” on Russia

At the G7 in Canada, President Trump didn’t just speak—he delivered a headline-making indictment.

Standing alongside Canada’s Prime Minister, he directly blasted Barack Obama and Justin Trudeau, accusing them of committing a “very big mistake” by booting Russia out of the G8. He warned that this move didn’t deter conflict—it unleashed it, and he insists it paved the way for the war in Ukraine.

Before the working sessions began, the two leaders fielded questions. The first topic: the ongoing trade negotiations between the U.S. and Canada. Trump didn’t hesitate to point out that the issue wasn’t personal—it was philosophical.

“It’s not so much holding up. I think we have different concepts,” Trump said. “I have a tariff concept, Mark [Carney] has a different concept, which is something that some people like.”

He made it clear that he prefers a more straightforward approach. “I’ve always been a tariff person. It’s simple, it’s easy, it’s precise and it just goes very quickly.”

Carney, he added, favors a more intricate framework—“also very good,” Trump said. The goal now, according to Trump, is to examine both strategies and find a path forward. “We’re going to look at both and we’re going to come out with something hopefully.”

When asked whether a deal could be finalized in a matter of days or weeks, Trump didn’t overpromise, but he left the door open. “It’s achievable but both parties have to agree.”

Then the conversation took an unexpected turn.

Standing next to Canada’s Prime Minister, whose predecessor helped lead that push, Trump argued that isolating Moscow may have backfired. “The G7 used to be the G8,” he said, pointing to the moment Russia was kicked out.

He didn’t hold back. “Barack Obama and a person named Trudeau didn’t want to have Russia in, and I would say that was a mistake because I think you wouldn’t have a war right now if you had Russia in.”

This wasn’t just a jab at past leaders. Trump was drawing a direct line from that decision to the war in Ukraine. According to him, expelling Russia took away any real chance at diplomacy before things spiraled.

“They threw Russia out, which I claimed was a very big mistake even though I wasn’t in politics then, I was loud about it.” For Trump, diplomacy doesn’t mean agreement—it means keeping adversaries close enough to negotiate.

“It was a mistake in that you spent so much time talking about Russia, but he’s no longer at the table. It makes life more complicated. You wouldn’t have had the war.”

Then he made it personal. Trump compared two timelines—one with him in office, and one without. “You wouldn’t have a war right now if Trump were president four years ago,” he said. “But it didn’t work out that way.”

Before reporters could even process Trump’s comments on Russia, he shifted gears again—this time turning to Iran.

Asked whether there had been any signs that Tehran wanted to step back from confrontation, Trump didn’t hesitate. “Yeah,” he said. “They’d like to talk.”

The admission was short but revealing. For the first time publicly, Trump confirmed that Iran had signaled interest in easing tensions. But he made it clear they may have waited too long.

“They should have done that before,” he said, referencing a missed 60-day negotiation window. “On the 61st day I said we don’t have a deal.”

Even so, he acknowledged that both sides remain under pressure. “They have to make a deal and it’s painful for both parties but I would say Iran is not winning this war.”

Then came the warning, delivered with unmistakable urgency. “They should talk and they should talk IMMEDIATELY before it’s too late.”

Eventually, the conversation turned back to domestic issues: specifically, immigration and crime.

He confirmed he’s directing ICE to focus its efforts on sanctuary cities, which he accused of protecting violent criminals for political purposes.

He pointed directly at major Democrat-led cities, saying the worst problems are concentrated in deep blue urban centers. “I look at New York, I look at Chicago. I mean you got a really bad governor in Chicago and a bad mayor, but the governor is probably the worst in the country, Pritzker.”

And he didn’t stop there. “I look at how that city has been overrun by criminals and New York and L.A., look at L.A. Those people weren’t from L.A. They weren’t from California most of those people. Many of those people.”

According to Trump, the crime surge isn’t just a local failure—it’s a direct consequence of what he called a border catastrophe under President Biden. “Biden allowed 21 million people to come into our country. Of that, vast numbers of those people were murderers, killers, people from gangs, people from jails. They emptied their jails into the U.S. Most of those people are in the cities.”

“All blue cities. All Democrat-run cities.”

He closed with a vow—one aimed squarely at the ballot box. Trump said he’ll do everything in his power to stop Democrats from using illegal immigration to influence elections.

“They think they’re going to use them to vote. It’s not going to happen.”

Just as the press corps seemed ready for more, Prime Minister Carney stepped in.

The momentum had clearly shifted toward Trump, and Carney recognized it. With a calm smile and hands slightly raised, he moved to wrap things up.

“If you don’t mind, I’m going to exercise my role, if you will, as the G7 Chair,” he said. “Since we have a few more minutes with the president and his team. And then we actually have to start the meeting to address these big issues, so…”

Trump didn’t object. He didn’t have to.

By then, the damage (or the impact) had already been done. He had steered the conversation, dropped one headline after another, and reshaped the narrative before the summit even began.

By the time Carney tried to regain control, it was already too late.

Wherever Trump goes, he doesn’t just attend the event—he becomes the event.

Thanks for reading! This post took time and care to put together, and we did our best to give this story the coverage it deserved.

If you like my work and want to support me and my team and help keep this page going strong, the most powerful thing you can do is sign up for the email list and become a paid subscriber.

Your monthly subscription goes further than you think. Thank you so much for your support.

This story was made possible with the help of Overton —I couldn’t have done it without him.

If you’d like to support his growing network, consider subscribing for the month or the year. Your support helps him expand his team and cover more stories like this one.

We both truly appreciate your support!

Business

The CBC is a government-funded giant no one watches

This article supplied by Troy Media.

By Kris Sims

By Kris Sims

The CBC is draining taxpayer money while Canadians tune out. It’s time to stop funding a media giant that’s become a political pawn

The CBC is a taxpayer-funded failure, and it’s time to pull the plug. Yet during the election campaign, Prime Minister Mark Carney pledged to pump another $150 million into the broadcaster, even as the CBC was covering his campaign. That’s a blatant conflict of interest, and it underlines why government-funded journalism must end.

The CBC even reported on that announcement, running a headline calling itself “underfunded.” Think about that. Imagine being a CBC employee asking Carney questions at a campaign news conference, while knowing that if he wins, your employer gets a bigger cheque. Meanwhile, Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre has pledged to defund the CBC. The broadcaster is literally covering a story that determines its future funding—and pretending there’s no conflict.

This kind of entanglement isn’t journalism. It’s political theatre. When reporters’ paycheques depend on who wins the election, public trust is shattered.

And the rot goes even deeper. In the Throne Speech, the Carney government vowed to “protect the institutions that bring these cultures and this identity to the world, like CBC/RadioCanada.” Before the election, a federal report recommended nearly doubling the CBC’s annual funding. Former heritage minister Pascale St-Onge said Canada should match the G7 average of $62 per person per year—a move that would balloon the CBC’s budget to $2.5 billion annually. That would nearly double the CBC’s current public funding, which already exceeds $1.2 billion per year.

To put that in perspective, $2.5 billion could cover the annual grocery bill for more than 150,000 Canadian families. But Ottawa wants to shovel more cash at an organization most Canadians don’t even watch.

St-Onge also proposed expanding the CBC’s mandate to “fight disinformation,” suggesting it should play a formal role in “helping the Canadian population understand fact-based information.” The federal government says this is about countering false or misleading information online—so-called “disinformation.” But the Carney platform took it further, pledging to “fully equip” the CBC to combat disinformation so Canadians “have a news source

they know they can trust.”

That raises troubling questions. Will the CBC become an official state fact-checker? Who decides what qualifies as “disinformation”? This isn’t about journalism anymore—it’s about control.

Meanwhile, accountability is nonexistent. Despite years of public backlash over lavish executive compensation, the CBC hasn’t cleaned up its act. Former CEO Catherine Tait earned nearly half a million dollars annually. Her successor, Marie Philippe Bouchard, will rake in up to $562,700. Bonuses were scrapped after criticism—but base salaries were quietly hiked instead. Canadians struggling with inflation and rising costs are footing the bill for bloated executive pay at a broadcaster few of them even watch.

The CBC’s flagship English-language prime-time news show draws just 1.8 per cent of available viewers. That means more than 98 per cent of TV-viewing Canadians are tuning out. The public isn’t buying what the CBC is selling—but they’re being forced to pay for it anyway.

Government-funded journalism is a conflict of interest by design. The CBC is expensive, unpopular, and unaccountable. It doesn’t need more money. It needs to stand on its own—or not at all.

Kris Sims is the Alberta Director for the Canadian Taxpayers Federation

Troy Media empowers Canadian community news outlets by providing independent, insightful analysis and commentary. Our mission is to support local media in helping Canadians stay informed and engaged by delivering reliable content that strengthens community connections and deepens understanding across the country.

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoWOKE NBA Stars Seems Natural For CDN Advertisers. Why Won’t They Bite?

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day agoUK finally admits clear evidence linking Pakistanis and child grooming gangs

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoLast day and last chance to win this dream home! Support the 2025 Red Deer Hospital Lottery before midnight!

-

conflict13 hours ago

conflict13 hours agoTrump: ‘We’ have control over Iranian airspace; know where Khomeini is hiding

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney praises Trump’s world ‘leadership’ at G7 meeting in Canada

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoCould the G7 Summit in Alberta be a historic moment for Canadian energy?

-

conflict1 day ago

conflict1 day agoIsrael bombs Iranian state TV while live on air

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoMinnesota shooter arrested after 48-hour manhunt