armed forces

Canadian veterans battle invisible wounds of moral injury and addiction

Moral injury, a unique psychological trauma, drives many Canadian veterans to substance use disorders as they struggle with inadequate support

When he was stationed in Bosnia in 1994, Steve Lamrock would drive a truck loaded with food through villages full of hungry people.

As a Canadian Armed Forces platoon quartermaster, one of Lamrock’s duties was transporting food to other soldiers involved in the United Nations Protection Force’s peacekeeping mission in the war-torn country.

“I had people starving to death, children starving to death,” he recalled, his wife seated beside him for support. “I could see, weekly, the deterioration in certain people in the community and the elderly from a lack of nutrition.”

Often, there was a surplus of rations.

“The UN policy was, if you can’t give exactly equal to both sides, you don’t give anything away,” he said, adding that it could trigger violent raids if you provided food to just one faction.

“So we would throw out food when there’s people starving to death.”

Moral dilemmas like these haunted Lamrock long after he retired from the military in 2009. Tormented by nightmares, he turned to alcohol to cope. “When I drank so much I passed out, I wouldn’t dream or remember the dreams as vividly or as often,” he said.

Lamrock — whose 24-year military career included tours in Afghanistan, Bosnia, Croatia, Kosovo and Iraq — was identified as suffering from psychological distress caused by the perception of having violated one’s moral or ethical beliefs. Experts are now calling this moral injury.

Moral injury is not formally recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, an authoritative manual on mental disorders. But experts and veterans say moral injury affects many individuals who serve in the military, and requires better institutional support and treatment than are currently available.

Moral injury and addiction

“[Moral injury presents as] shame, guilt and anger that occurs when someone is exposed to an event that goes against their moral values, standards or ethics,” said Dr. Don Richardson, a psychiatrist and scientific director of the MacDonald Franklin Operational Stress Injury Research Centre in London, Ont. The centre studies the impact of stress injuries on military personnel, veterans and first responders.

Moral injury can result not only from witnessing or causing harm, but also from being affected by an organization’s actions or inactions, Richardson says.

The term moral injury was first introduced in the 1990s by American psychiatrist Dr. Jonathan Shay, who worked with veterans of the Vietnam War. It gained wider recognition following the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, when traditional treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) — such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy — were proving to be only partially effective.

While fear is often at the core of traditional PTSD cases, feelings of guilt, shame, anger and betrayal are more strongly linked to cases of moral injury, says Dr. Anthony Nazarov, associate director of the MacDonald Franklin Operational Stress Injury Research Centre and an expert on moral injury.

Nearly 60 per cent of Canadian Armed Forces personnel deployed in NATO operations in Afghanistan reported exposure to morally injurious events, according to a 2018 study co-authored by Nazarov. Those exposed to such events demonstrated a greater likelihood of developing PTSD and major depressive disorders.

Dr. Ronald Shore, a research scientist and assistant professor in psychiatry at Queen’s University, says individuals suffering from moral injury often develop coping strategies due to a lack of support to help them process traumatic experiences.

One common coping mechanism is substance use, he says.

“You’re constantly feeling like something is wrong with you, that you’ve done something wrong … that leads to that self-regulation with addiction,” Shore said.

Lamrock says his experiences in Bosnia — and the habits he developed afterwards — deeply affected him and his family.

He recalled promising his young daughter they would do something fun after a night’s rest. “‘No, you won’t, Daddy, you won’t get up,’” she had replied, knowing he would likely be too hungover.

“That was my motivation to quit,” he said.

Betrayal

It is common for veterans suffering from moral injury to feel angry or betrayed due to the military’s actions or lack of support.

“[A person feels] betrayed by policies, betrayed by leaders, betrayed by organizations,” said Nazarov.

This has been the case for Gordon Hurley, 37, whose 14-year career in the Canadian Armed Forces included tours in Afghanistan, Africa and Iraq.

“When you get out, there’s nothing,” Hurley said. “If you think that Veterans Affairs is going to support you … they will, but you’re gonna have to fight for it.”

Hurley was medically discharged from the military in 2021 due to various physical and mental health challenges, including PTSD. He says Veterans Affairs requires him to continually prove the severity of his injuries to maintain disability support and benefits, such as reimbursements for retinal surgery and rehabilitation.

Hurley says that having to repeatedly prove his injuries to Veterans Affairs has been frustrating. “You were the ones who released me from the military … for these injuries, but now you are asking me to prove them back to you?” he said.

The Canadian Armed Forces redirected inquiries about support for veterans with moral injury and substance use disorder to Veterans Affairs Canada.

In an emailed statement to Canadian Affairs, Veterans Affairs spokesperson Josh Bueckert said mental health-care practitioners who work with veterans are “well aware of moral injury” and recognize the condition is often associated with operational stress injuries.

Bueckert said the department provides funding to organizations such as the Atlas Institute for Veterans and Families, which has a moral injury toolkit for veterans.

He also noted the department offers veterans a range of mental health resources, including access to 11 operational stress injury clinics and a network of 12,000 mental health professionals. Bueckert said veterans also have access to treatments for substance use disorder and for conditions such as “trauma-and-stressor-related disorders.”

Hurley acknowledges all these benefits are available, but says they are hard-won.

“All those benefits listed you get, but unless your condition has been [approved by the department], you do not receive those benefits,” he said.

‘Never-ending battle’

Josh Muir, 49, served nearly 14 years in the military and was deployed twice to Afghanistan. After sustaining soft tissue damage, hearing damage and spinal injuries in a 2010 improvised explosive device attack, he was medically discharged from the military — something he says he opposed because the military had become his entire identity.

“As soon as I’ve crossed this threshold, I no longer really have a clear picture of who I am, what I am, what use I might play in the future, and where to go from here,” he said.

He described feeling discarded by the military. “I was very quickly turned from a valuable asset into a liability that needed to be rid of as quickly and as expeditiously as possible,” said Muir, who turned to alcohol as a crutch.

|

Canadian Forces veteran Josh Muir and his son Max at a beach in Vancouver, April 2024. [Photo Credit: Atlas Institute for Veterans and Families]

Shore, of Queen’s University, says recovering from moral injury and substance use disorder can require rebuilding one’s identity as the sense of purpose and belonging one gets from being part of the military fades.

Therapies such as acceptance and commitment therapy help veterans accept difficult emotions and commit to taking actions that align with their values. Another treatment called narrative therapy helps veterans separate their problems from their identity. These therapies can be effective at helping veterans recover, says Richardson, of the MacDonald Franklin Operational Stress Injury Research Centre.

Richardson also encourages veterans to seek peer support through groups like Operational Stress Injury Social Support or True Patriot Love Foundation.

David Fascinato joined the military in 2005 and served in psychological operations, including a deployment to Afghanistan in 2010.

Fascinato, who has since left the military, has struggled with mental health issues and moral injury. He says he has come to realize that veterans need organizations that offer community, purpose and tools to rebuild their sense of self.

This realization led him to co-found Team Rubicon Canada, a volunteer disaster relief organization that conducts missions in Canada and abroad. “Doing things with others for others, that’s where it helps reduce substance misuse and provides an off-ramp,” he said.

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis, or donate to our journalism fund.

Fascinato has also found purpose by serving as executive director of Heroic Hearts Project Canada, an organization that supports veterans and first responders with alternative mental health treatments such as psychedelics.

Richardson and Shore view psychedelic-assisted therapy — which uses psychedelics to disrupt ingrained neural patterns — as a promising treatment for moral injury and substance use disorder..

Shore says support for psychedelic trials with veterans is still limited due to safety concerns and insufficient research. However, Canadian veterans are seeking psychedelic therapy in overseas retreats in places like Mexico and Peru.

Hurley says he was only able to recover from his alcoholism after seeking treatment at a psychedelic retreat in Tijuana, Mexico in 2022. “Only after I did ibogaine did I get released from [alcohol addiction],” he said, referring to a type of psychedelic drug.

While the production, sale and possession of psychedelics remain illegal in Canada, Health Canada in 2023 amended its Special Access Program, which allows health-care providers to request psychedelic medications for patients with life-threatening or treatment-resistant conditions.

In Muir’s case, he was able to gain control of his addiction and mental health issues after completing a two-month residential program at a treatment centre on Vancouver Island. The cost of the program was covered by Veterans Affairs.

While Muir is grateful to have his treatment costs covered, he says he would like to see Veterans Affairs generally improve the support it offers veterans, including offering more personalized assistance in the transition to civilian life.

He describes his experience with the Canadian Armed Forces’ transition program as taking in “information via fire hose,” with overwhelming seminars and a lack of personal guidance to navigate the process.

“There’s little services and ceremonies,” said Muir. “But ultimately you have to go back to you being a small cog in a large machine.”

“I felt like I was going to become Army Surplus, just like the items in the store that sit there after their function has been superseded by newer models.”

“I think it’s absurd,” said Fascinato. “We have to pick up the proverbial sword and shield, or in this case pen and pad of paper, and seemingly wage this never-ending battle for access to care that shouldn’t be this difficult to get.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

If you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

armed forces

Mark Carney Thinks He’s Cinderella At The Ball

And we all pay when the dancing ends

How to explain Mark Carney’s obsession with Europe and his lack of attention to Canada’s economy and an actual budget?

Carney’s pirouette through NATO meetings, always in his custom-tailored navy blue power suits, carries the desperate whiff of an insecure, small-town outsider who has made it big but will always yearn for old-money credibility. Canada is too young a country, too dynamic and at times a bit too vulgar to claim equal status with Europe’s formerly magnificent and ancient cultures — now failed under the yoke of globalism.

Hysterical foreign policy, unchecked immigration, burgeoning censorship and massive income disparity have conquered much of the continent that many of us used to admire and were even somewhat intimidated by. But we’ve moved on. And yet Carney seems stuck, seeking approval and direction from modern Europe — a place where, for most countries, the glory days are long gone.

Carney’s irresponsible financial commitment to NATO is a reckless and unnecessary expenditure, given that many Canadians are hurting. But it allowed Carney to pick up another photo of himself glad-handing global elites to whom he just sold out his struggling citizens.

From the Globe and Mail

“Prime Minister Mark Carney has committed Canada to the biggest increase in military spending since the Second World War, part of a NATO pledge designed to address the threat of Russian expansionism and to keep Donald Trump from quitting the Western alliance.

Mr. Carney and the leaders of the 31 other member countries issued a joint statement Wednesday at The Hague saying they would raise defence-related spending to the equivalent of 5 per cent of their gross domestic product by 2035.

NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte said the commitment means “European allies and Canada will do more of the heavy lifting” and take “greater responsibility for our shared security.”

For Canada, this will require spending an additional $50-billion to $90-billion a year – more than doubling the existing defence budget to between $110-billion and $150-billion by 2035, depending on how much the economy grows. This year Ottawa’s defence-related spending is due to top $62-billion.”

You’ll note that spending money we don’t have in order to keep President Trump happy is hardly an elbows up moment, especially given that the pledge followed Carney’s embarrassing interactions with Trump at the G7. I’m all for diplomacy but sick to my teeth of Carney’s two-faced approach to everything. There is no objective truth to anything our prime minister touches. Watch the first few minutes of the video below.

The portents are bad. This from the Globe:

We are poorer than we think. Canadians running their retirement numbers are shining light in the dark corners of household finances in this country. The sums leave many “anxious, fearful and sad about their finances,” according to a Healthcare of Ontario Pension Plan survey recently reported in these pages.

Fifty-two per cent of us worry a lot about our personal finances. Fifty per cent feel frustrated, 47 per cent feel emotionally drained and 43 per cent feel depressed. There is not one survey indicator to suggest Canadians have made financial progress in 2025 compared with 2024.

The video below is a basic “F”- you to Canadians from a Prime Minister who smirks and roles his eyes when questioned about his inept money management.

He did spill the beans to CNN with this unsettling revelation about the staggering numbers we are talking about:

Signing on to NATO’s new defence spending target could cost the federal treasury up to $150 billion a year, Prime Minister Mark Carney said Tuesday in advance of the Western military alliance’s annual summit.

The prime minister made the comments in an interview with CNN International.

“It is a lot of money,” Carney said.

This guy was a banker?

We are witnessing the political equivalent of a vain woman who blows her entire paycheque to look good for an aspirational event even though she can’t afford food or rent. Yes, she sparkled for a moment, but in reality her domaine is crumbling. All she has left are the photographs of her glittery night. Our Prime Minister is collecting his own album of power-proximity photos he can use to wallpaper over his failures as our economy collapses.

The glass slipper doesn’t fit.

Trish Wood is Critical is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

armed forces

It’s not enough to just make military commitments—we must also execute them

From the Fraser Institute

By Jake Fuss and Grady Munro

To reach 2 per cent of GDP this year, the federal government is committing an additional $9.3 billion towards the military budget. Moreover, to reach 3.5 per cent of GDP by 2035, it’s estimated the government will need to raise yearly spending by an additional $50 billion—effectively doubling the annual defence budget from $62.7 billion to approximately $110 billion.

As part of this year’s NATO summit, Canada and its allies committed to increase annual military spending to reach 5 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) by 2035. While this commitment—and the government’s recent push to meet the previous spending target of 2 per cent of GDP—are important steps in fulfilling Canada’s obligations to the alliance, there are major challenges the federal government will need to overcome to execute these plans.

Since 2014, members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) have committed to spend at least 2 per cent of GDP (a measure of overall economic output) on national defence. Canada had long-failed to fulfill this commitment, to the ire of our allies, until the Carney government recently announced a $9.3 billion boost to defence spending (up to a total of $62.7 billion) that will get us to 2 per cent of GDP during the 2025/26 fiscal year.

However, just as Canada reached the old target, the goal posts have now moved. As part of the 2025 NATO summit, alliance members (including Canada) committed to reach an increased spending target of 5 per cent of GDP in 10 years. The new target is made up of two components: core military spending equivalent to 3.5 per cent of GDP, and another 1.5 per cent of GDP for other defence-related spending.

National defence is a core function of the federal government and the Carney government deserves credit for prioritizing its NATO commitments given that past governments of different political stripes have failed to do so. Moreover, the government is ensuring that Canada remains in step with its allies in an increasingly dangerous world.

However, there are major challenges that arise once you consider how the government will execute these commitments.

First, both the announcement that Canada will reach 2 per cent of GDP in military spending this fiscal year, and the future commitment to spend up to 3.5 per cent of GDP on defence by 2035, represent major fiscal commitments that Canada’s budget cannot simply absorb in its current state.

To reach 2 per cent of GDP this year, the federal government is committing an additional $9.3 billion towards the military budget. Moreover, to reach 3.5 per cent of GDP by 2035, it’s estimated the government will need to raise yearly spending by an additional $50 billion—effectively doubling the annual defence budget from $62.7 billion to approximately $110 billion. However, based on the last official federal fiscal update, the federal government already plans to run an annual deficit this year—meaning it spends more than it collects in revenue—numbering in the tens of billions, and will continue running large deficits for the foreseeable future.

Given this poor state of finances, the government is left with three main options to fund increased military spending: raise taxes, borrow the money, or cut spending in other areas.

The first two options are non-starters. Canadian families already struggle under a tax burden that sees them spend more on taxes than on food, shelter, and clothing combined. Moreover, raising taxes inhibits economic growth and the prosperity of Canadians by reducing the incentives to work, save, invest, or start a business.

Borrowing the money to fund this new defence spending will put future generations of Canadians in a precarious situation. When governments borrow money and accumulate debt (total federal debt is expected to reach $2.3 trillion in 2025-26), the burden of this debt falls squarely on the backs of Canadians—likely in the form of higher taxes in the future. Put differently, each dollar we borrow today must be paid back by more than a dollar in higher taxes tomorrow.

This leaves cutting spending elsewhere as the best option, but one that requires the government to substantially readjusts its priorities. The federal government devotes considerable spending towards areas that are not within its core responsibilities and which shouldn’t have federal involvement in the first place. For instance, the previous government launched three major initiatives to provide national dental care, national pharmacare and national daycare, despite the fact that all three areas fall squarely under provincial jurisdiction. Instead of continuing to fund federal overreach, the Carney government should divert spending back to the core function of national defence. Further savings can be found by reducing the number of bureaucrats, eliminating corporate welfare, dropping electric vehicle subsidies, and many other mechanisms.

There is a fourth option by which the government could fund increased defence spending, which is to increase the economic growth rate within Canada and enjoy higher overall revenues. The problem is Canada has long-suffered a weak economy that will remain stagnant unless the government fundamentally changes its approach to tax and regulatory policy.

Even if the Carney government is able to successfully adjust spending priorities to account for new military funding, there are further issues that may inhibit money from being spent effectively.

It is a well-documented problem that military spending in Canada is often poorly executed. A series of reports from the auditor general in recent years have highlighted issues with the readiness of Canada’s fighter force, delays in supplying the military with necessary materials (e.g. spare parts, uniforms, or rations), as well as delays in delivering combat and non-combat ships needed to fulfill domestic and international obligations. All three of these cases represent instances in which poor planning and issues with procurement and supply chains) are preventing government funding from translating into timely and effective military outcomes.

The Carney government has recently made major commitments to increase military funding to fulfill Canada’s NATO obligations. While this is a step in the right direction, it’s not enough to simply make the commitments, the government must execute them as well.

-

Business7 hours ago

Business7 hours agoRFK Jr. says Hep B vaccine is linked to 1,135% higher autism rate

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta Independence Seekers Take First Step: Citizen Initiative Application Approved, Notice of Initiative Petition Issued

-

Crime20 hours ago

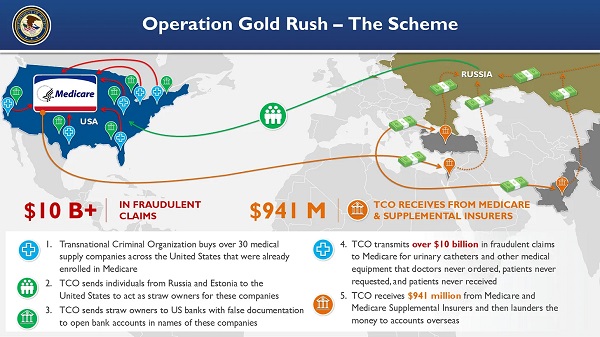

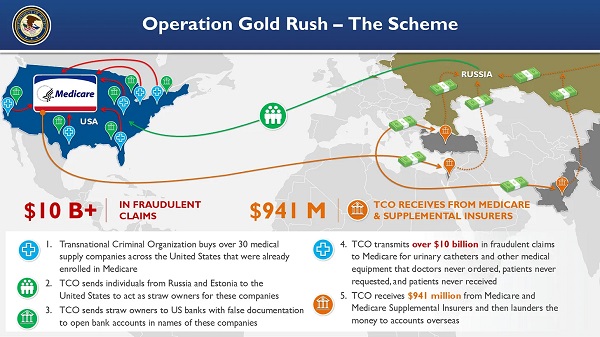

Crime20 hours agoNational Health Care Fraud Takedown Results in 324 Defendants Charged in Connection with Over $14.6 Billion in Alleged Fraud

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoSuspected ambush leaves two firefighters dead in Idaho

-

Health19 hours ago

Health19 hours agoRFK Jr. Unloads Disturbing Vaccine Secrets on Tucker—And Surprises Everyone on Trump

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoWhy the West’s separatists could be just as big a threat as Quebec’s

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCanada Caves: Carney ditches digital services tax after criticism from Trump

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoThe Game That Let Canadians Forgive The Liberals — Again