Energy

Canada’s Climate Fetish Could Decimate Key Industry For First Nations

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

Obsessed with the faux climate crisis, the Canadian government in Ottawa seemingly discounts altogether the social and economic benefits of natural gas to First Nations communities of the country’s western region.

Approximately 5% of the world’s gas comes from Canada, mainly from the vast Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin underlying several provinces, including British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan. In 2023, the country ranked fifth in global production behind the U.S., Russia, Iran and China.

Some First Nations communities — a designation that takes in indigenous people living south of the Arctic Circlehave — historically faced challenges in terms of economic development and social well-being. Limited access to education, healthcare and infrastructure has resulted in lower living standards compared to the national averagea — fact that I observed firsthand as a researcher in British Columbia. Unemployment rates are often higher in First Nations communities, and poverty remains a persistent issue.

However, oil and gas development has provided a pathway to prosperity for many of these communities. Liquified natural gas (LNG) projects, for example, require a significant workforce in both construction and operational phases. This translates into direct employment opportunities and much needed income for First Nations people otherwise lacking financial security.

The development of natural gas resources also necessitates infrastructure upgrades in nearby communities. These can include the construction or enhancements of roads, bridges and communication networks. Such improvements benefit the entire community by providing access to markets, educational opportunities and other essential services.

“For far too long, First Nations could only watch as others built generational wealth from the resources of our traditional lands” says Eva Clayton, president of the Nisga’a Lisims government. “But times are changing.”

First Nations participation in natural gas development goes beyond economic benefits. It represents an opportunity for communities to assert their self-determination and participate in shaping their own future. Communities can participate in natural gas projects through equity ownership and various arrangements, including Impact Benefit Agreements. According to the Canada Energy Centre, more than 75 First Nations and Métis communities in Alberta and British Columbia have agreed to ownership stakes in energy projects, including the Coastal GasLink pipeline and major transportation networks for oil sands production.

One such example is the recent Musqueam Partnership agreement by FortisBC, which will share the benefits of the Tilbury LNG facility’s expansion phase to begin in 2025. First Nations beneficiaries will include communities of the Snuneymuxw, T’Sou-ke, Esquimalt, Scia’new, Pacheedaht, Pauquachin, Huu-ay-aht, Kyuquot/Checleseht, Toquaht, Uchucklesaht and Ucluelet. Similarly, the Woodfibre LNG project to begin production in 2027 will directly benefit the Squamish community.

DemandObsessed with the faux climate crisis, the Canadian government in Ottawa seemingly discounts altogether the social and economic benefits of natural gas to First Nations communities for natural gas in North America and across the world should ensure increasing prosperity into the future, unless the federal government’s climate fetish undermines the industry.

Just such a possibility has prompted an alarm to be sounded by the First Nations LNG Alliance—a collective of communities supportive of LNG development in British Columbia.

“First Nations have made their choice about the LNG opportunity, informed by research and consultation,” says Karen Ogen, CEO of the LNG Alliance.

“However, when 88 environmental groups and other organizations recently demanded an end to LNG, no one bothered to talk to us,” she said. “I view that as a ‘re-colonization’ of energy by environmentalists. It’s a type of eco-colonialism that First Nations people like me are all-too familiar with, particularly as we seek to diversify our economies and provide opportunities for young people and future generations.”

Ms. Ogen’s complaint of “eco-colonialism” is not unlike the charge of “climate imperialism” that has been leveled against Western elites by leaders of the Global South who bristle at being pressured to adopt “green” agendas at the expense of actual economic development supported gas and other fossil fuels.

Indeed, the sentiments of Ms. Ogen almost certainly resonate with those who favor common sense over ideology. “Canadian LNG is Indigenous LNG, and that is good for the world and good for all of us here,” she says.

Vijay Jayaraj is a Research Associate at the CO2 Coalition, Arlington, Virginia. He holds a master’s degree in environmental sciences from the University of East Anglia, U.K.

Energy

Unceded is uncertain

Tsawwassen Speaker Squiqel Tony Jacobs arrives for a legislative sitting. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

From Resource Works

Cowichan case underscores case for fast-tracking treaties

If there are any doubts over the question of which route is best for settling aboriginal title and reconciliation – the courts or treaty negotiations – a new economic snapshot on the Tsawwassen First Nation should put the question to rest.

Thanks to a modern day treaty, implemented in 2009, the Tsawwassen have leveraged land, cash and self-governance to parlay millions into hundreds of millions a year, according to a new report by Deloitte on behalf of the BC Treaty Commission.

With just 532 citizens, the Tsawwassen First Nation now provides $485 million in annual employment and 11,000 permanent retail and warehouse jobs, the report states.

Deloitte estimates modern treaties will provide $1 billion to $2 billion in economic benefits over the next decade.

“What happens, when you transfer millions to First Nations, it turns into billions, and it turns into billions for everyone,” Sashia Leung, director of international relations and communication for the BC Treaty Commission, said at the Indigenous Partnership Success Showcase on November 13.

“Tsawwassen alone, after 16 years of implementing their modern treaty, are one of the biggest employers in the region.”

BC Treaty Commission’s Sashia Leung speaks at the Indigenous Partnerships Success Showcase 2025.

Nisga’a success highlights economic potential

The Nisga’a is another good case study. The Nisga’a were the first indigenous group in B.C. to sign a modern treaty.

Having land and self-governance powers gave the Nisga’a the base for economic development, which now includes a $22 billion LNG and natural gas pipeline project – Ksi Lisims LNG and the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission line.

“This is what reconciliation looks like: a modern Treaty Nation once on the sidelines of our economy, now leading a project that will help write the next chapter of a stronger, more resilient Canada,” Nisga’a Nation president Eva Clayton noted last year, when the project received regulatory approval.

While the modern treaty making process has moved at what seems a glacial pace since it was established in the mid-1990s, there are some signs of gathering momentum.

This year alone, three First Nations signed final treaty settlement agreements: Kitselas, Kitsumkalum and K’omoks.

“That’s the first time that we’ve ever seen, in the treaty negotiation process, that three treaties have been initialed in one year and then ratified by their communities,” Treaty Commissioner Celeste Haldane told me.

Courts versus negotiation

When it comes to settling the question of who owns the land in B.C. — the Crown or First Nations — there is no one-size-fits-all pathway.

Some First Nations have chosen the courts. To date, only one has succeeded in gaining legal recognition of aboriginal title through the courts — the Tsilhqot’in.

The recent Cowichan decision, in which a lower court recognized aboriginal title to a parcel of land in Richmond, is by no means a final one.

That decision opened a can of worms that now has private land owners worried that their properties could fall under aboriginal title. The court ruling is being appealed and will almost certainly end up having to go to the Supreme Court.

This issue could, and should, be resolved through treaty negotiations, not the courts.

The Cowichan, after all, are in the Hul’qumi’num treaty group, which is at stage 5 of a six-stage process in the BC Treaty process. So why are they still resorting to the courts to settle title issues?

The Cowichan title case is the very sort of legal dispute that the B.C. and federal governments were trying to avoid when it set up the BC Treaty process in the mid-1990s.

Accelerating the process

Unfortunately, modern treaty making has been agonizingly slow.

To date, there are only seven modern implemented treaties to show for three decades of works — eight if you count the Nisga’a treaty, which predated the BC Treaty process.

Modern treaty nations include the Nisga’a, Tsawwassen, Tla’amin and five tribal groups in the Maa-nulth confederation on Vancouver Island.

It takes an average of 10 years to negotiate a final treaty settlement. Getting a court ruling on aboriginal title can take just as long and really only settles one question: Who owns the land?

The B.C. government has been trying to address rights and title through other avenues, including incremental agreements and a tripartite reconciliation process within the BC Treaty process.

It was this latter tripartite process that led to the Haida agreement, which recognized Haida title over Haida Gwaii earlier this year.

These shortcuts chip away at issues of aboriginal rights and title, self-governance, resource ownership and taxation and revenue generation.

Modern treaties are more comprehensive, settling everything from who owns the land and who gets the tax revenue from it, to how much salmon a nation is entitled to annually.

Once modern treaties are in place, it gives First Nations a base from which to build their own economies.

The Tsawwassen First Nation is one of the more notable case studies for the economic and social benefits that accrue, not just to the nation, but to the local economy in general.

The Tsawwassen have used the cash, land and taxation powers granted to them under treaty to create thousands of new jobs. This has been done through the development of industrial, commercial and residential lands.

This includes the development of Tsawwassen Mills and Tsawwassen Commons, an Amazon warehouse, a container inspection centre, and a new sewer treatment plant in support of a major residential development.

“They have provided over 5,000 lease homes for Delta, for Vancouver,” Leung noted. “They have a vision to continue to build that out to 10,000 to 12,000.”

Removing barriers to agreement

For First Nations, some of the reticence in negotiating a treaty in the past was the cost and the loss of tax exemptions. But those sticking points have been removed in recent years.

First Nations in treaty negotiations were originally required to borrow money from the federal government to participate, and then that loan amount was deducted from whatever final cash settlement was agreed to.

That requirement was eliminated in 2019, and there has been loan forgiveness to those nations that concluded treaties.

Another sticking point was the loss of tax exemptions. Under Section 87 of Indian Act, sales and property taxes do not apply on reserve lands.

But under modern treaties, the Indian Act ceases to apply, and reserve lands are transferred to title lands. This meant giving up tax exemptions to get treaty settlements.

That too has been amended, and carve-outs are now allowed in which the tax exemptions can continue on those reserve lands that get transferred to title lands.

“Now, it’s up to the First Nation to determine when and if they want to phase out Section 87 protections,” Haldane said.

Haldane said she believes these recent changes may account for the recent progress it has seen at the negotiation table.

“That’s why you’re seeing K’omoks, Kitselas, Kitsumkalum – three treaties being ratified in one year,” she said. “It’s unprecedented.”

The Mark Carney government has been on a fast-tracking kick lately. But we want to avoid the kind of uncertainty that the Cowichan case raises, and if the Carney government is looking for more things to fast-track that would benefit First Nations and the Canadian economy, perhaps treaty making should be one of them.

Resource Works News

Alberta

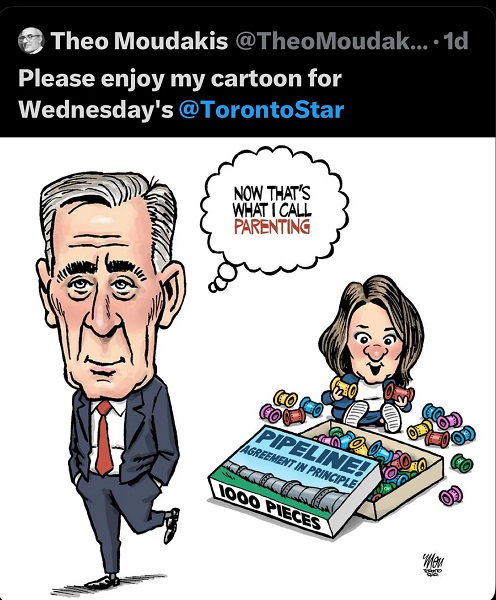

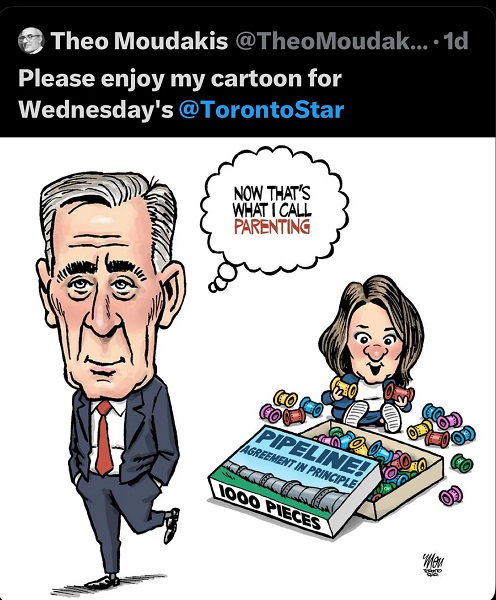

This new Canada–Alberta pipeline agreement will cost you more than you think

Canada and Alberta’s new net-zero energy deal is being promoted as progress, but it also brings rising costs. In this video, I break down the increase to Alberta’s industrial carbon price, how those costs can raise fuel, heating, and grocery prices, and why taxpayer-funded carbon-capture projects and potential pipeline delays could add even more. Here’s what this agreement could mean for Canadians.

Watch Nataliya Bankert’s latest video.

-

Business19 hours ago

Business19 hours agoRecent price declines don’t solve Toronto’s housing affordability crisis

-

Daily Caller18 hours ago

Daily Caller18 hours agoTech Mogul Gives $6 Billion To 25 Million Kids To Boost Trump Investment Accounts

-

National16 hours ago

National16 hours agoCanada Needs an Alternative to Carney’s One Man Show

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoNew era of police accountability

-

National2 days ago

National2 days agoMedia bound to pay the price for selling their freedom to (selectively) offend

-

C2C Journal2 days ago

C2C Journal2 days agoLearning the Truth about “Children’s Graves” and Residential Schools is More Important than Ever

-

armed forces2 days ago

armed forces2 days agoGlobal Military Industrial Complex Has Never Had It So Good, New Report Finds

-

Automotive4 hours ago

Automotive4 hours agoPower Struggle: Governments start quietly backing away from EV mandates