espionage

Beijing’s Secret Biowar: National Security Experts Probe Fentanyl and Expanding Viral Bioweapons Program After COVID-19 Lab Leak

A new book argues that Beijing transformed a pandemic lab leak into a global field test — and is now accelerating bioweapons development and fentanyl production from Pakistan to Wuhan.

In 2022, synthetic opioids killed more than 75,000 Americans. But according to the authors of China’s Total War Strategy: Next-Generation Weapons of Mass Destruction, these fentanyl deaths were not simply the result of regulatory failures or a national addiction crisis. They were casualties in a covert biochemical war — one that Western governments remain unwilling to confront. This war, the authors argue, is not waged by rogue actors, but directed by the strategic command of the Chinese Communist Party, wielding an arsenal that includes fentanyl, cognitive warfare, genetically engineered viruses — including the bat coronavirus they say leaked accidentally from Wuhan and was later weaponized through statecraft — and a global criminal underworld mobilized as an instrument of policy.

“This is strategic activity that is driven by hostile state intent,” the authors write, referring to opioid trafficking networks that fuse China’s state-backed chemical supply chains with the industrial-scale production infrastructure of Mexican cartels.

They describe the fentanyl epidemic as “biochemical warfare against a highly clustered group of Western countries” — with the Five Eyes nations as primary targets — and argue that synthetic narcotics can no longer be viewed solely through the lens of organized crime. Instead, they should be understood as instruments in a state-enabled campaign of mass disruption orchestrated by Beijing.

Within the book’s evidentiary framework, China’s alleged fentanyl campaign — paired with the global consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic — emerges as the most consequential demonstration to date of what the authors describe as Beijing’s increasingly effective total war doctrine.

The thesis is unflinchingly dark, confrontational — and, to many readers, will seem conspiratorial. Yet the authors, a team of American national security and military intelligence veterans, construct their case with layers of evidence and the methods of intelligence tradecraft. They connect the Chinese Party-state’s export of fentanyl precursor chemicals and chemical engineering expertise to Mexican cartels, its cognitive warfare operations on Western social media platforms, and its role in the COVID-19 pandemic — forging these seemingly disparate elements into a predictive model of how the Chinese Communist Party is reengineering modern warfare.

This doctrine of clandestine total war, rooted in Chinese military texts, assumes that Beijing — which has signaled intentions to invade Taiwan as early as 2027 — cannot prevail in a conventional conflict against a coalition that may include the United States, Japan, Taiwan, Australia, South Korea, and the United Kingdom. Instead, the strategy prioritizes asymmetric, non-kinetic warfare designed to degrade an adversary’s societal resilience, probe its critical systems, and map its crisis response — all before open conflict begins.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Cognitive War and Elite Capture

The unfolding shadow war — and the development of next-generation clandestine weapons — is, the authors argue, being waged behind the smokescreen of foreign interference and influence operations. Total War Strategy outlines a multi-track offensive: some elements are deniable yet increasingly brazen and visible, while others remain deeply concealed and poorly understood.

The visible front includes familiar forms of state aggression — industrial espionage, economic coercion, transnational repression, intellectual property theft, election interference, and the covert financing of protest movements. The second, more insidious track, is cognitive warfare: the manipulation of information systems, digital platforms, and social media networks to fracture democratic cohesion and weaken public trust from within. China’s influence operations, according to the authors, serve not merely to shape narratives but to provide cover for far more dangerous strategic objectives.

They cite a pattern of “targeted influence campaigns to undermine, corrupt, persuade and destabilize regimes such as Brazil, Mexico, Canada, Panama, some European Union states and many Sub-Saharan African nations.” These efforts are complemented by sustained economic coercion, intimidation of diaspora communities, trafficking in weapons and narcotics, and the exploitation of academic and technological partnerships — all deployed as tools of indirect warfare.

“Such non-lethal efforts in unsuspecting societies and regimes often succeed,” the authors write, “because feckless leaders are too naive to grasp the insidious assassin’s mace approach.”

In this argument, fentanyl is a primary weapon — and states like Canada remain in denial about their institutional role in enabling the shift of Chinese production and trafficking routes.

Seen through the lens of North America’s fentanyl crisis — in which hundreds of thousands have died while policymakers continue to treat the emergency as a public health or law enforcement issue — the authors argue the Chinese Communist Party is already attacking Western defenses via transnational crime proxies.

“These hostile state extensions are engaged in biochemical warfare against a tightly clustered group of Western countries,” they write. “The effects have been devastating but are fragile and reversible once the massive information asymmetries regarding network structure are rebalanced. The successful collapse of these syndicates in the Five Eyes nations will reduce the likelihood of spread to other countries. The inverse is also true.”

The fentanyl trade, they argue, defies the logic of conventional criminal markets. Unlike heroin or cocaine, synthetic opioids annihilate their own user base. “Fentanyl-laced heroin does not generate a stable population of consumers,” they note, “given the high fatality rates of users.” In a rational market, a drug enterprise seeks to cultivate long-term demand. Fentanyl destroys it. And yet, production and distribution continue to scale exponentially.

Unlike traditional cartels, which can be disrupted through leadership arrests or financial seizures, a state-backed trafficking network is more resilient, adaptive, and strategically dangerous. The CCP’s role — supplying precursor chemicals, trafficking infrastructure, and, in some cases, managerial oversight — elevates the threat from criminal to geopolitical.

That threat, they note, is not evenly distributed. The most devastating effects of synthetic narcotics are concentrated in the Five Eyes intelligence alliance: the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand. Europe, despite its liberalized approach to drug markets, has seen no comparable surge in fentanyl fatalities — yet.

COVID-19: Accident Evolves into ‘Field Test’

The authors’ thesis is stark: China’s covert bioweapons program did not merely survive the COVID-19 pandemic — it accelerated, diversified, and deepened in its aftermath.

While much of the world remains fixated on the Wuhan Institute of Virology as the plausible origin point of the COVID-19 crisis, the authors caution that Wuhan was only one node in a vast and opaque network.

Drawing on open-source intelligence, forensic research, and a review of Chinese scientific literature, the authors contend that the Chinese Communist Party has dramatically expanded its clandestine biological weapons program across multiple pathogen types and geographic locations — including, notably, a military-linked facility in Islamabad, Pakistan. Their analysis synthesizes pre- and post-pandemic data, Chinese-language publications, patent filings, and sensitive research documents — some of which disappeared from public access shortly after surfacing.

To build their case, the authors first established a pre-COVID baseline of biological research activity in China, then overlaid post-pandemic developments. What emerges, they argue, is a sprawling, dual-use biological weapons network spanning labs in Wuhan, Harbin, and Beijing — embedded within China’s vast research infrastructure and operated under both civilian and military auspices. Their findings surpass what has been publicly disclosed by Western governments, though they align with intelligence assessments from the United Kingdom, Germany, the FBI, and now the CIA.

According to the authors, the original SARS-CoV-2 outbreak was the result of an accidental lab leak at the Wuhan Institute of Virology in late 2019. They tie the incident to a long-documented pattern of high-risk bat coronavirus gain-of-function experiments conducted at the institute — many of which, they argue, fall within the broader scope of the People’s Liberation Army’s biological warfare program. That program, they assert, enjoys top-level political and military protection from Major General Chen Wei — a senior figure in the CCP’s elite scientific apparatus — whose subordinates have collaborated freely with researchers in Canada and the United States under the guise of pandemic preparedness.

This claim aligns with intelligence findings from CSIS, Canada’s national security agency, and several of its Five Eyes counterparts. But the authors go further: they assert that rather than responding transparently to the accidental lab leak in Wuhan, the Chinese regime quickly adapted — transforming a domestic crisis into a global strategic opportunity.

According to their analysis, CCP-linked intelligence services closely monitored how other nations — including the United States and its allies — responded to the pandemic across public health, economic, and defense sectors. This real-time surveillance, the authors suggest, turned COVID-19 into a de facto field test: a live demonstration of how resilient the West would be in the face of sudden, high-impact biological disruption — and how such disruption could be exploited.

Crucially, they stress that China’s bioweapons research is not limited to coronaviruses. On the far more dangerous end of the threat spectrum, they say, the CCP is pursuing weaponization of high-fatality pathogens such as Nipah virus and African swine fever. Even within the SARS-CoV-2 family, the work continues. One January 2024 study, cited by the authors, describes a new synthetic variant engineered at the Beijing University of Chemical Technology — work they suggest poses even greater risks than the original pandemic strain.

Perhaps most alarming is the convergence they document between genetic engineering and delivery technologies. The CCP, the authors assert, is pairing its pathogen research with advanced nanotechnology platforms — opening the door to next-generation weapons that are more targeted, more concealable, and far more difficult to defend against. Supporting evidence includes experimental data and patent filings that demonstrate efforts to bind engineered viruses with nanoparticles designed for precise delivery.

Even if only portions of the authors’ findings and predictions prove accurate, the book’s well-supported claims suggest that governments — from Washington to Taipei, Berlin, Ottawa, and Canberra — should be urgently educating their populations about the realities of hybrid warfare campaigns waged by Beijing and other hostile states. At a minimum, they should be intensifying preparations for the plausible — if nightmarish — scenarios that Total War Strategy outlines.

With millions already dead since 2020 from the bat coronavirus pandemic and the fentanyl epidemic — both of which, even the most cautious experts acknowledge, trace back to Chinese sources, whether intentionally produced or not — anything less than a serious, studied response to the theory and evidence presented in Total War Strategy would constitute a dangerous dereliction of duty.

Authors Dr. Ryan Clarke, LJ Eads, Dr. Robert McCreight, and Dr. Xiaoxu Lin are national security experts with diverse government and professional backgrounds, and co-founders of the CCP BioThreats Initiative.

Crime

The “Strong Borders Act,” Misses the Mark — Only Deep Legal Reforms Will Confront Canada’s Fentanyl Networks

The fallout is a grim roll call of major investigations that collapsed before trial in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec: Project E-Pirate, E-Nationalize, Syndicato, Cobra, Brisa, and Endgame all aborted.

Bill C-2, Ottawa’s so-called “Strong Borders Act,” promises to secure Canada’s frontiers with new surveillance powers, sweeping ministerial discretion, and higher penalties. But as veteran Canadian investigators know, the bill misses the point. It is an omnibus solution that expands the state’s reach online, while leaving untouched the very legal choke points that have made Canada a permissive financial platform and fentanyl laboratory for cartels, Triads, and state-linked terror networks.

For more than a decade, Canadian and U.S. enforcement leaders have pointed to the same failures. Police are confronting transnational fentanyl labs, a flood of Chinese chemical precursors, Hezbollah-linked laundering, and Mexican cartels setting up on Canadian soil.

Yet they are forced to fight these threats with laws “never designed for today’s criminal landscape,” as Canadian Chiefs of Police president Thomas Carrique recently warned.

Former RCMP investigator Calvin Chrustie testified before British Columbia’s Cullen Commission that, due to judicial blockages arising from Charter of Rights rulings, by 2015 it had become effectively impossible to obtain wiretaps on Sinaloa Cartel figures in Vancouver.

This year, RCMP Assistant Commissioner David Teboul said a proliferation of “commercial-grade chemistry” fentanyl labs in British Columbia — like the sophisticated factory dismantled last year in Falkland, north of Lake Okanagan, where Mexican cartels have quietly taken over domestic biker gang networks — underlined the urgent need for legislative reform.

Canada wasn’t always so overwhelmed by lethal foreign gangs. What happened? Overly permissive immigration rules and porous borders explain part of the story, but the deeper problem lies in the laws that have steadily eroded enforcement power since the early 1990s.

Instead of enabling prosecutions against transnational traffickers of humans, narcotics, and weapons, unintended consequences from misguided jurisprudence surrounding Canada’s Charter of Rights now ensure these cases almost always collapse, or are simply avoided by the Crown.

Two Supreme Court rulings — Stinchcombe and Jordan — have gutted the capacity to prosecute complex crime. Stinchcombe requires exhaustive disclosure of sensitive intelligence, often impossible in Five Eyes investigations that depend on close cooperation between Canada and the United States.

Jordan imposes strict trial ceilings that tick down while Stinchcombe disclosure battles drag on. Criminal lawyers know these two rulings function as trump cards stacked in favor of their clients.

The fallout is a grim roll call of major investigations that collapsed before trial in British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec: Project E-Pirate, E-Nationalize, Syndicato, Cobra, Brisa, and Endgame all aborted. Project Collecteur — a landmark probe linking Hezbollah and foreign terror-financing networks across Canadian cities to transnational drug money laundering, built on U.S. and Australian intelligence — barely made it to court, despite its far-reaching implications.

It was crippled by RCMP corruption and by underfunded, risk-averse agencies that abandoned Canadian leads painstakingly developed by Five Eyes partners.

How bad was it?

Farzam Mehdizadeh, a major Iranian money launderer and suspected weapons proliferation actor who ran a Toronto currency exchange while shuttling bags of drug cash between Toronto and Montreal, escaped back to Iran just as the RCMP was poised to arrest him on money-laundering charges. The beneficiary of a leaky national police force, evidently.

A senior U.S. enforcement source told The Bureau that during Project Collecteur, the RCMP stumbled onto an even bigger Chinese money launderer while probing Iranian networks, but the agency ignored the file — reportedly unable to shift its original investigation focus onto new enterprise targets.

These kinds of policing failures and decisions are part of the reason President Donald Trump has said senior U.S. investigators told him that Canada lacks the resources and capacity to confront fentanyl trafficking gangs.

In Washington, there is frustration — and at times a lack of understanding — that Stinchcombe either bars or effectively scares the Mounties out of cooperating with U.S. agencies or sharing intelligence.

Derek Maltz, former DEA chief under President Trump, pointed to the Falkland fentanyl super-lab case — part of a U.S.-led probe into Chinese precursor suppliers — as the latest example of “historical issues with the RCMP not sharing properly,” calling it a “major disaster that happened on that big lab in British Columbia.”

“It goes down to the basic information sharing, the antiquated laws,” Maltz said. After meeting with current Canadian police leadership, he concluded: “They’re so far behind and the laws are so antiquated and so archaic.”

The cost is staggering. Officers walk away from enterprise files, knowing they cannot meet disclosure or trial deadlines. Prosecutors refuse to take high-risk cases. U.S. agencies stop sharing intelligence that could be exposed in open court. Canada defaults to “low-hanging fruit” prosecutions while the upper echelons of global networks operate with near impunity.

Meanwhile, at the border, permissive Non-Resident Importer rules allow foreign entities to move chemical precursors through Canadian ports under layers of corporate opacity. Chinese logistics hubs repackage bulk fentanyl shipments bound for Vancouver, obscuring Canada’s visibility into their true origin. Once in Canada, packages can be collected by foreign nationals who further conceal their identities. To visualize the scheme, think of an “end-to-end encryption” app — Chinese trafficking networks enjoy the same kind of seamless concealment when shipping narcotics into Canada.

At the same time, Vancouver’s port — stripped of federal police under Jean Chrétien’s Liberal government — has container inspection rates below one percent, according to a British Columbia study.

It doesn’t seem that Bill C-2 will do anything to address these core vulnerabilities. It gives Ottawa broad powers to expand online surveillance, which may help with the drug networks that now brazenly advertise street sales on social platforms. But it would do so by subjecting all Canadians to invasive cyber surveillance. The bill does not target the transnational criminals who are already easy to identify and well known to law enforcement. These networks continue to operate openly in Canada, confident that the Charter shields them from real prosecution.

Meanwhile, experts warn that parts of C-2 resemble Ottawa’s wish list of new powers tossed into a grab bag. The effect is the opposite of inspiring public confidence or addressing the real enforcement crisis. As written, Bill C-2 could do more harm than good. Mark Carney’s government should shelve it and start again with the reforms Canada actually needs.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

espionage

North Americans are becoming numb to surveillance.

Eliminating Quiet Skies is hopefully just a start. The government spent $200 million a year following up to 50 people a day for a program that in its history never once led to an arrest, or thwarted a single criminal act.

Last year, former Hawaii Congresswoman and Presidential Candidate Tulsi Gabbard was placed in a surveillance program called Quiet Skies by the Transportation and Security Administration. Across eight flights she was subject to intrusive searches, followed by bomb-sniffing dogs, and trailed by three Federal Air Marshals per flight, who if they were following procedure were attempting to listen to her conversations, following her to airport exits to see who if anyone met her, and even recording how often and at what times she went to the bathroom.

To cover the story I contacted the TSA. They no-commented the main question – “TSA does not confirm or deny whether any individual has matched to a risk-based rule,” they said – but they added, as if in mitigation: ”Simply matching to a risk-based rule does not constitute derogatory information about an individual.”

In other words: “We can’t say if Ms. Gabbard was in the program, but if she was, don’t draw conclusions, because we do this even to innocent people.”

Before Quiet Skies was discontinued by this administration, it was a symbol of the steep decline of federal enforcement since 9/11. The government spent $200 million a year following up to 50 people a day for a program that in its history never once led to an arrest, or thwarted a single criminal act. Despite its demonstrated inutility and grave civil liberties concerns it was re-funded year after year because this is what our government does now: it gathers information on its own citizens as an end in itself.

In a week in which the question of whether federal security officials always tell the truth to Congress is back in the news, it’s worth noting that it’s been 13 years since then-National Intelligence Director James Clapper answered, “No, sir,” and “Not wittingly” when Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon asked, “Does the NSA collect any type of data at all on millions, or hundreds of millions of Americans?”

Clapper later explained that he’d responded in the “least most untruthful manner.”

That episode solidified the principle that if you lie about mass surveillance programs in America, even under oath, you not only get to keep your job, you get to be hired as a professional truth-teller after retirement, a National Security Analyst for CNN. If you try to tell the truth about the same issues, your options are prison or leaving the country forever.

In those 13 years since, Americans became numb to surveillance. It was once a core principle that government couldn’t or shouldn’t spy on citizens without predication. Now much of the country accepts as inevitable the idea that every move we make is being recorded and analyzed.

We know emails and phone conversations are being collected passively, via programs of dubious legality, and the mountains of data we leave behind as our lives move online– from geolocations of cell phones to GPS tracking to travel, banking, and medical records – are increasingly fodder for overt and covert acquisition by federal analysts. As Google admitted last week, federal officials partnered with companies not just to monitor speech but to suppress it on a grand scale.

A lot of these changes have their roots in War on Terror programs that exchanged predication for a pre-crime theory out of Minority Report. Quiet Skies was the paradigmatic example of a program that could take endless liberties with the Constitution because it was secret. When you gather information with no intention of going to court, as the TSA did with Quiet Skies, you never have to justify yourself to a judge. This leads to a lot of what one court called “the exact sort of ‘general, exploratory rummaging’ that the Fourth Amendment was designed to prevent.”

This is a betrayal not just of the public but of people we trained at taxpayer expense to do real and important work. Former Marshal Robert MacLean put it best when he said “The air marshal’s job is to protect the cockpit and the pilots. Let somebody else do the intelligence.”

Similarly in the last decade current and former FBI agents – fellow witness Tristan Leavitt’s firm has represented a number of them – have talked about how since 9/11, the FBI spends less time building cases but does more generalized spying, much of it political. One agent I interviewed said “The distinction between people who believe bad thoughts and people who do bad things” has been “completely lost” on our government since 9/11.

Once you start down the road of collecting information on innocent people, it creates the intellectual justification for doing it again and again. From a contracting perspective, this is the proverbial self-licking ice cream cone, a spiral of endless expense. Morally, all this information-gathering reverses the natural political order, giving elected officials undeserved and unearned power over their bosses – the voters. These programs all need to be reevaluated. A lot of them have to go. People who lie about them in this chamber need to be fired.

Let’s hope the elimination of Quiet Skies is just the beginning. Thank you.

-

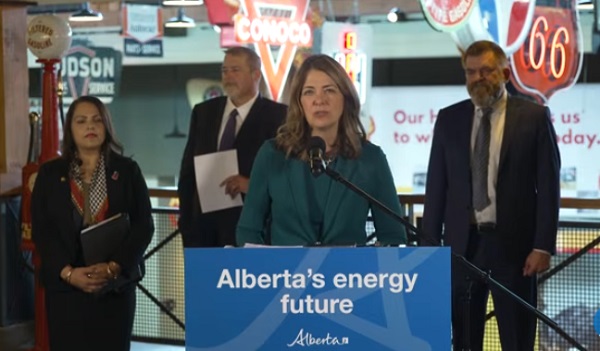

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta’s E3 Lithium delivers first battery-grade lithium carbonate

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days agoCanada’s EV subsidies are wracking up billions in losses for taxpayers, and not just in the auto industry

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoLA skyscrapers for homeless could cost federal taxpayers over $1 billion

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day agoThe “Strong Borders Act,” Misses the Mark — Only Deep Legal Reforms Will Confront Canada’s Fentanyl Networks

-

Agriculture22 hours ago

Agriculture22 hours ago“We Made it”: Healthy Ostriches Still Alive in Canada

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoUK Government Dismisses Public Outcry, Pushes Ahead with Controversial Digital ID Plan

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoNuclear power outperforms renewables every time

-

Artificial Intelligence2 days ago

Artificial Intelligence2 days agoAI chatbots a child safety risk, parental groups report