Christopher Rufo

An exclusive interview with a Haitian immigrant from Charleroi, Pennsylvania

and

Under the Biden administration, an unprecedented flow of 7 million migrants has entered the United States, through licit and illicit channels, including more than 1 million parolees. Several hundred thousand of those have come from Haiti.

Those Haitians have entered through a designated route: the parole program for Cubans, Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans (CHNV). The initiative, which the Biden administration enacted in October 2022 and recently declined to renew, allows individuals from those four countries to enter the United States for up to two years; for Cubans and Haitians, it also lets them collect welfare benefits, such as food stamps, cash assistance, and employment services. What began as a two-year parole program could, for many, turn into a longer stay, as the Department of Homeland Security announced in June that it would extend Haitians’ eligibility for Temporary Protected Status to February 2026.

The federal government runs a multibillion-dollar apparatus of government agencies, NGOs, and other institutions to settle the current wave of Haitian migrants in cities and towns across the country—including Charleroi, Pennsylvania, a small Rust Belt borough that has watched its demographics transform.

We spoke with many of Charleroi’s old residents and with some of the recent Haitian arrivals, including a man who asked to be identified only as Rene, out of fear of reprisal. Rene, 28, arrived in Charleroi at the beginning of this year. He was a truck driver in Haiti and has worked to integrate into American life.

But he also raised concerns: about exploitation, corruption, and the refusal of many Haitians to assimilate. Rene’s story reveals the fraught dynamics of migration and provides a vivid illustration of how the system works.

The following interview transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Christopher Rufo for Substack: Can you walk us through the process of migrating from Haiti to the United States?

Rene: It’s called the Humanitarian Parole Program. My sponsor applied for me. My sponsor is my cousin’s husband. My cousin has been in the U.S. for about two years. He was living there legally before me. He went to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services website and filed an application. He had to prove his income and an address to host me. The U.S. government knows everything about him through his Social Security number. He has a clean record. When I got approved, they sent me travel authorization documents in a PDF. It is pretty easy. It takes time to get approved; for some people, it can take a year. It took me six months to get approved.

But some people manage to leave without going through the airport. They cross the border of the Dominican Republic and from there, they leave the country. Once they’re in the Dominican Republic, I’m not sure how they leave, but I think some people do manage to come to the U.S. that way.

Christopher Rufo for Substack: And what happens when you arrive? How did you get to Charleroi?

Rene: I paid for my own plane ticket to New York City, and my cousin picked me up. I came to the country basically with nothing. When I got here four days later, I went to the DHS office to get government assistance, like food stamps.

I had to wait two and a half months to get my work authorization card, which is required if you’re an immigrant and want to work in the U.S. I had to pay $410 for it, but they raised the price and now you have to pay $470.

Once I got my work authorization card, I started working at Fourth Street Foods in Charleroi, through Celebes Staffing Services. A friend who had worked for them before told them I was looking for a job. Because I speak a little bit of English and I know computers, I wasn’t an assembly line worker. I was doing a job called “paperwork” and then I had to work on the computer. And then after that, I was a supervisor. I wasn’t working directly with the company. My paychecks came from Celebes.

Christopher Rufo for Substack: What was it like working at the facility?

Rene: There’s two Fourth Street Foods facilities, a north plant and a south plant, both in Charleroi. I worked at the north plant, which had around 250 to 280 employees—not including the Americans in the office. I’m talking about the assembly line workers.

I think room one had 60 people and they were all from different agencies. I can be working for Celebes and the person next to me could be working for Wellington Staffing Agency. So you never know how many people are from which agency. It is not only Haitians working there; there are also Asians and Africans. But the Americans, they work in the offices.

Assembly line workers only got $10 an hour, but they recently raised it to $12. In my jobs, I started at $10, then $11.75, and finally $16 an hour when I became a supervisor. I worked there for about 2 months.

We worked in the freezer. If you’ve been to Charleroi, you will see a lot of people in high temperatures wearing coats. Fourth Street Foods does not provide coats. We had to buy our own.

It’s not an easy job, working in the cold. If you cannot work the hardest you can, you’ll get fired so they can get better workers. Fourth Street Foods is not for the weak. You can’t work, you go home. Pretty simple and easy to get fired.

Fourth Street Foods needs these immigrants because they accept any treatment. The company knows that it can use them because they don’t know their rights. It’s sad.

Christopher Rufo for Substack: What was your experience with the staffing company?

Rene: The staffing agency took money from our wages. If the real rate was $16 an hour, they might take $4, saying it was for transportation and to run the agency. And they give you the rest of the money.

It would be much better to just apply directly to the company, but they make a business out of it. I don’t think $10 or $12 an hour is enough. It would be more if we worked directly with the company, but these agencies are somehow making some money out of their employees and it seems like it benefits the company, too.

It wasn’t enough money. I was just doing it temporarily. I didn’t want to just sit at home and do nothing. I was going to do it until I found something better.

Fourth Street Foods should stop using agencies and let people work directly with the company. No one provided a contract or any documents, which is why I wanted to quit so badly. I needed proof of employment or income to get a loan to buy a car and they couldn’t give it to me.

The agency business is suspicious. Some agencies are trying to compete with others to get more workers so they can get more money. From my second week working for them, I knew something wasn’t right. They call you an employee, but they can’t give you proof of employment. That’s not fair. I’ve even heard scary stories, like people getting shot in this business.

Christopher Rufo for Substack: You must be referring to the murder of Boyke Budiarachman two years ago, who was allegedly killed by a hitman hired by his competitor, Keven Van Lam. The motive for the crime appears to be business rivalry, following Budiarachman’s sale of his staffing company that supplied workers to Fourth Street Foods.

Rene: Yes, I had heard that but didn’t know the names. Fourth Street used to hire workers under the table, but the authorities cracked down on that. Now you need a work card and Social Security number. I tried to work for them before I had my work card, but they wouldn’t let me (Fourth Street Foods denies having hired workers under-the-table.).

Christopher Rufo for Substack: And after you left Fourth Street Foods, where did you go?

Rene: I work at an Amazon warehouse now, making $19.25 an hour. When I started earning more, I informed the public benefit office and stopped receiving government assistance.

I’m in a three-bedroom apartment with five people, including my cousin. Rent is around $800 to $850, not including utilities.

It was harsh in Haiti. There’s a lot of crazy stuff that happened. The gang stuff. A lot of madness. I had never thought about leaving Haiti, but since all the crazy stuff started happening there, I changed my mind. As a truck driver, I was making good money by Haitian standards, but the insecurity made me leave. It’s much better here.

I’m only here for two years. I don’t know if the program I’m in will get renewed. But for now, I know I’m here for two years.

Christopher Rufo for Substack: Some people in Charleroi have expressed concerns that many recent Haitian migrants are not interested in assimilating. What is your perspective on that?

Rene: Some Haitians are acting bad or weird. Some Haitians that came here were from the countryside. There is a lot of things about living in the city they’re not too familiar with. It’s a big cultural change.

I can say that I’m a little educated but most of the other Haitians aren’t, especially the ones that came from Chile or Brazil and had to walk through 13 or 14 South American countries to come here. They’re all “country” and don’t trust white people because they say white people are racist and don’t like them. They don’t want to talk to white people. I’ve seen people work at Fourth Street for two years and still not speak English or understand the traffic signs and traffic laws. Many Haitians fail their driver’s test here. Some of them blame racism for why they keep failing their driving test. So they go to Florida to get their driver’s license. Maybe it’s easier to get in Florida than here.

I’m not mad at Americans. I’m frustrated with myself, my people, my government, and our politicians.

Christopher Rufo is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Christopher Rufo

The “No Kings” Protest Is Pure Fantasy

Christopher F. Rufo

Christopher F. Rufo

The underlying theory is that Donald Trump is an authoritarian leader on the cusp of becoming king.

I spent Father’s Day weekend in Hood River, Oregon, and stumbled upon the local “No Kings” anti-Trump protest. The crowd was populated mostly by Baby Boomers, who appeared to be living out a political fantasy, in which they could “stop fascism” by reenacting the protest movements of their youth. One sign, typical of the genre, derided Trump as a “felon, rapist, con man”; another riffed on Mary Poppins, reading “super callous, fragile, racist, sexist, Nazi POTUS.”

The underlying theory of this protest, which reportedly drew upward of 5 million demonstrators nationwide, is that Donald Trump is an authoritarian leader on the cusp of becoming king. The only way to stop him is to flood the streets and persuade the American people that Trump is a rotten character with despotic ambitions.

The theory, of course, is nonsense. Trump is a duly elected president. He is working with Congress on the budget. His deportation policy, which lent momentum to the weekend’s demonstrations, is predicated on enforcing existing law. Though President Trump contested the results of his first reelection campaign, he ultimately relented and peacefully transferred power to President Joe Biden—hardly the behavior of a tyrant.

Yet the protests are not without utility for the Left. They are not intended to grapple with the reality of the Trump presidency but to submerge reality in fantasy. The first step in entrenching the Left’s fictions in the public mind is to cultivate a sense of hysteria. In the president’s first term, crowds wore vagina-shaped hats and marched in the bitter cold. The tone of the “No Kings” protest was no less absurd, with women in Handmaid’s Tale costumes warning that Trump would reduce them to sex slaves.

The next step is to turn public energy into a threat. As seen in Los Angeles earlier this month, the Left’s more aggressive factions can operate alongside “mostly peaceful protests,” aiming to provoke law enforcement into overreacting. During Trump’s first term, leftist activists often played a double game—promoting “nonviolent” demonstrations for women’s rights or racial justice while allowing more confrontational elements to intimidate Trump supporters.

This time, immigration is the flash point. Trump has tied his presidency to mass deportations. The Left believes it can stop him by carefully shaping public opinion. That means highlighting emotional—if sometimes misleading—stories of deportation victims and sympathetic portrayals of protesters clashing with National Guard troops. These narratives are designed to paint Trump as an authoritarian and the Left as the resistance, with the aim of driving his approval ratings low enough to weaken his presidency.

The irony is that Trump does not have the power of a king—or, arguably, even the full power of the presidency, as established in Article II of the Constitution. District courts have blocked many of his policies down to the most minute detail, sometimes within hours of their adoption. A federal judge even prohibited the administration from removing gender-related content from government websites.

At the Hood River protest, I noticed a generational divide. The Baby Boomers were the most gullible, engaging in 1960s protest nostalgia and genuinely believing that America was under threat of incipient fascism. The younger generation, which came to political consciousness during the Trump era, seemed more skeptical. At the edge of the protest, I saw a group of teenage boys holding signs that read “Ban Onions” and “Ban Scratchy Blankets.” They seemed to see through the fiction of “No Kings,” viewing left-wing Baby Boomers, rather than Trump, as the rightful targets of satire and rebellion.

I hope that this attitude prevails. For 60 years, the Boomers have held a grip on the American political narrative; it has not been a story that conduced to national well-being. America elected Trump, in part, to demolish the remaining fantasies of the 1968 generation. Yes, no kings—and no more lies.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

Business

Washington Got the Better of Elon Musk

The tech tycoon’s Department of Government Efficiency was prevented from achieving its full reform agenda.

It seems that the postmodern world is a conspiracy against great men. Bureaucracy now favors the firm over the founder, and the culture views those who accumulate too much power with suspicion. The twentieth century taught us to fear such men rather than admire them.

Elon Musk—who has revolutionized payments, automobiles, robotics, rockets, communications, and artificial intelligence—may be the closest thing we have to a “great man” today. He is the nearest analogue to the robber barons of the last century or the space barons of science fiction. Yet even our most accomplished entrepreneur appears no match for the managerial bureaucracy of the American state.

Musk will step down from his position leading the Department of Government Efficiency at the end of May. At the outset, the tech tycoon was ebullient, promising that DOGE would reduce the budget deficit by $2 trillion, modernize Washington, and curb waste, fraud, and abuse. His marketing plan consisted of memes and social media posts. Indeed, the DOGE brand itself was an ironic blend of memes, Bitcoin, and Internet humor.

Three months later, however, Musk is chastened. Though DOGE succeeded in dismantling USAID, modernizing the federal retirement system, and improving the Treasury Department’s payment security, the initiative as a whole has fallen short. Savings, even by DOGE’s fallible math, will be closer to $100 billion than $2 trillion. Washington is marginally more efficient today than it was before DOGE began, but the department failed to overcome the general tendency of governmental inertia.

Musk’s marketing strategy ran into difficulties, too. His Internet-inflected language was too strange for the average citizen. And the Left, as it always does, countered proposed cuts with sob stories and personal narratives, paired with a coordinated character-assassination attempt portraying Musk as a greedy billionaire eager to eliminate essential services and children’s cancer research.

However meretricious these attacks were, they worked. Musk’s popularity has declined rapidly, and the terror campaign against Tesla drew blood: the company’s stock has slumped in 2025—down around 20 percent—and the board has demanded that Musk return to the helm.

But the deeper problem is that DOGE has always been a confused effort. It promised to cut the federal budget by roughly a third; deliver technocratic improvements to make government efficient; and eliminate waste, fraud, and abuse. As I warned last year, no viable path existed for DOGE to implement these reforms. Further, these promises distracted from what should have been the department’s primary purpose: an ideological purge.

Ironically, this was the one area where DOGE made major progress. In just a few months, the department managed to dismantle one of the most progressive federal agencies, USAID; defund left-wing NGOs, including cutting over $1 billion in grants from the Department of Education; and advance a theory of executive power that enabled the president to slash Washington’s DEI bureaucracy.

Musk also correctly identified the two keys to the kingdom: human resources and payments. DOGE terminated the employment of President Trump’s ideological opponents within the federal workforce and halted payments to the most corrupted institutions, setting the precedent for Trump to withhold funds from the Ivy League universities. At its best, DOGE functioned as a method of targeted de-wokification that forced some activist elements of the Left into recession—a much-needed program, though not exactly what was originally promised.

Ultimately, DOGE succeeded where it could and failed where it could not. Musk’s project expanded presidential power but did not fundamentally change the budget, which still requires congressional approval. Washington’s fiscal crisis is not, at its core, an efficiency problem; it’s a political one. When DOGE was first announced, many Republican congressmen cheered Musk on, declaring, “It’s time for DOGE!” But this was little more than an abdication of responsibility, shifting the burden—and ultimately the blame—onto Musk for Congress’s ongoing failure to take on the politically unpopular task of controlling spending.

With Musk heading back to his companies, it remains to be seen who, if anyone, will take up the mantle of budget reform in Congress. Unfortunately, the most likely outcome is that Republicans will revert to old habits: promising to balance the budget during campaign season and blowing it up as soon as the legislature convenes.

The end of Musk’s tenure at DOGE reminds us that Washington can get the best even of great men. The fight for fiscal restraint is not over, but the illusion that it can be won through efficiency and memes has been dispelled. Our fate lies in the hands of Congress—and that should make Americans pessimistic.

Subscribe to Christopher F. Rufo.

For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.

-

Business7 hours ago

Business7 hours agoRFK Jr. says Hep B vaccine is linked to 1,135% higher autism rate

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta Independence Seekers Take First Step: Citizen Initiative Application Approved, Notice of Initiative Petition Issued

-

Crime19 hours ago

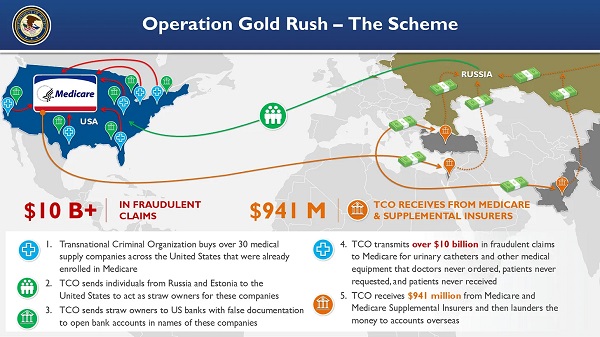

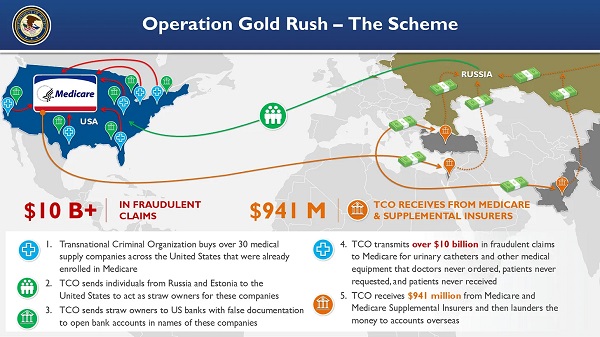

Crime19 hours agoNational Health Care Fraud Takedown Results in 324 Defendants Charged in Connection with Over $14.6 Billion in Alleged Fraud

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day agoSuspected ambush leaves two firefighters dead in Idaho

-

Health19 hours ago

Health19 hours agoRFK Jr. Unloads Disturbing Vaccine Secrets on Tucker—And Surprises Everyone on Trump

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoWhy the West’s separatists could be just as big a threat as Quebec’s

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCanada Caves: Carney ditches digital services tax after criticism from Trump

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoThe Game That Let Canadians Forgive The Liberals — Again